The Sati tradition, an ancient Indian practice where widows self-immolated on their husbands’ funeral pyres, is a complex and contentious subject. Though banned by the British Government in 1829 and subsequently, by the Government of independent India in 1956 and 1987, incidents of sati still continue to be sporadically reported from various parts of India.

The debate continues because of its controversial nature fuelled by the political divide. While the Hindu right often downplays it, calling it a colonial construct, the left-leaning academia goes in the opposite direction and perhaps amplifies the problem. This is where Meenakshi Jain’s book Sati: Evangelicals, Baptist Missionaries, and the Changing Colonial Discourse can be of great help. It helps answer the two key questions that arise from either side of the political spectrum:

- How common was sati practice throughout Indian history?

- Did the British colonialists play any part in misreporting or misrepresenting this problem?

To get to the heart of the first question, we must also take a look at the religious aspect of the sati tradition. After all, that’s where it comes from.

Sati in Hindu religion

Meenakshi Jain argues that for a considerable period in Indian history, the religio-legal texts contained no definitive reference to sati. On the other hand, the British fraudulently built a case for Vedic sanction of the rite by substituting the last word of the funeral hymn (Rig Veda 10.18.7) from agre (earlier or first) to agneh (fire). Interestingly, there were disagreements among the British scholars in the 18th and 19th century, but they were lost in the pages of history. And a common perception emerged that the practice is encouraged by the Vedas.

But… Vedas are not the only sacred texts for Hindus, there are many more. And as we explore these texts, the references keep coming. Let me mention a few.

Sati is mentioned in the Mahabharata. It’s also there in the Puranas. Some Smriti writers have referred to it as well. Even Kalhana mentions it in Rajatarangini where he recorded the cases of two queens of Kashmir who had bribed their ministers to induce them to come to the cremation ground and dissuade them from their seemingly voluntary decision to join their husbands on the pyre.

From the above instances, we can make the following observations:

- Sati, as a practice, was present in ancient India. Even if not directly commanded by the religious texts, it was embedded in the religio-social fabric.

- The practice seems voluntary, but it can be said that at least some kind of social pressure used to be there.

Sati in the recorded history

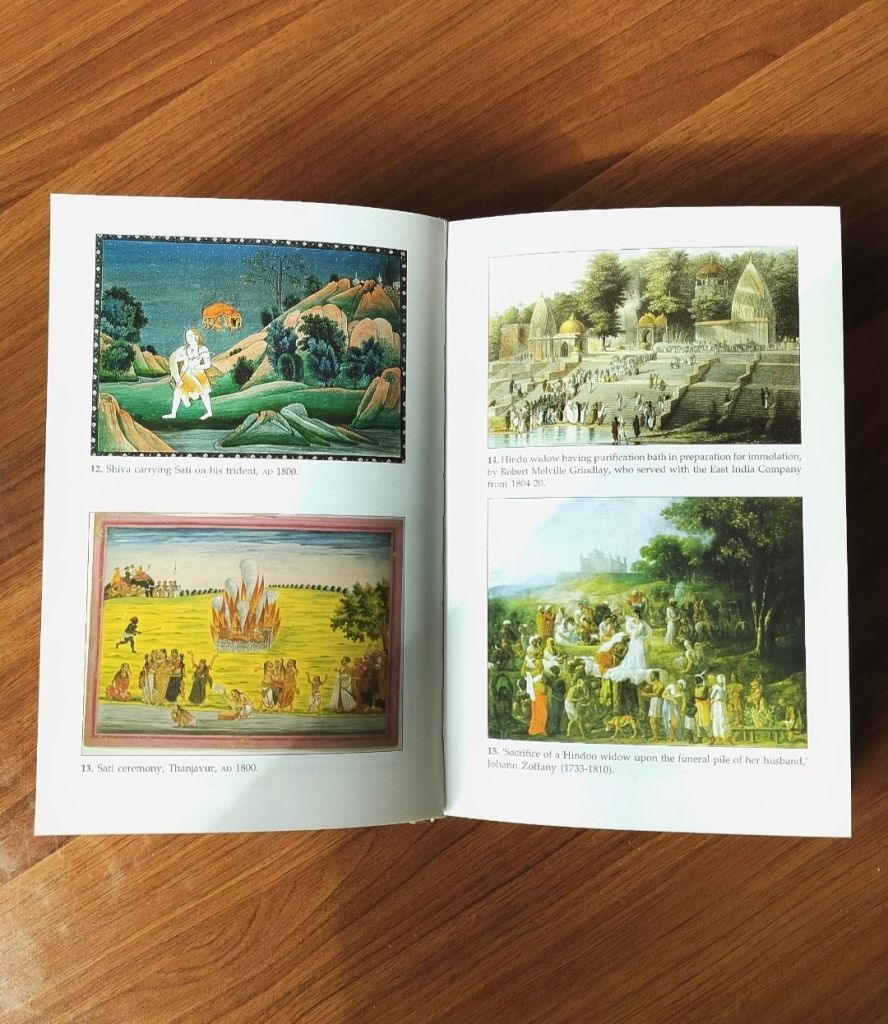

The earliest historical account of sati available is by Diodorus of Sicily (second half of the first century BC). Another foreign reference is by Strabo, the Greek geographer and historian (born 63 BC). He stated that the Greeks under Alexander found the custom prevalent among the Katheae in the Punjab. The epigraphic records also mention the presence of sati in different parts of India during the first millennium of common era.

Once again, it’s easy to suggest that the practice has had a continued presence in India. What about outside India? Have such practices existed in other Indo-European cultures? Yes, they have. Almost in all ancient civilisations such as China, Egypt or pre-Christian Europe, you’d find the elements of similar practices.

A more difficult question to answer in this regard is whether or not this was forced upon a widow. For instance, in Marwar (Rajasthan), from 1562 to 1843, a total of 47 queens, 101 concubines, 74 female slaves and others, and 5 men immolated themselves on the death of rulers. In the same period, 48 queens did not commit such an act.

What to make of it?

There can be two ways to look at it. One, the practice was voluntary, so in that sense, it appears more like a suicide. Two, just because some queens survived does not mean that there was no social pressure on them (or those who succumbed to it). I think, the second perspective makes more sense, given the consequences.

It’s worth noting that by the medieval times, we do not find many instances of sati. The practice was gradually struggling into existence. And that’s where the role of British colonialists comes.

What happened during the British colonial period?

In the early 19th century, somehow, the sati suddenly assumed the appearance of a pervasive practice, which demanded intervention by the colonial Government. Why? This is the central question posed in Meenakshi Jain’s book. That, when all the evidence suggests that the practice was on a decline, why did the conversations around it grow with such passion and zeal?

One must remember that the British colonialism wasn’t just about the rule of the British. A significant effort was also devoted to spread the Christian faith in India and get rid of its pagan practices which the Britishers viewed as evil. And that’s where the clues lie. With the arrival of the British, a concerted effort was made to highlight the positive attributes of Christianity, and while doing so, criticise other religious and cultural groups.

The Evangelical-missionary critique of Hinduism spotlighted the issue of sati. It seemed that the British had found a strawman to demonise the entire religion. From 1803 onwards, more organised effort was put in to raise the issue. Multiple surveys were conducted. The results, though, seem dubious to say the least. The officials randomly arrived at some numbers, sometimes quoting a few hundred, sometimes tens of thousands. The government figures also did not agree with that.

All of that did not seem to matter and the missionary campaign against sati began to spread. ‘Sati was bad’ was a sensible thing to say, but it was also helpful to bring more people into the fold of Christianity. Eventually the practice was banned by the government and the Britishers took full credit for it. They even underplayed the contribution made by the locals, as one of them said, “Ram Mohan Roy accepted Jesus as one of the religious masters.”

The British colonisers tried to remake India in their own image. While doing so, they did some nice things, and some — let’s just say — not-so-nice. The important thing for India, just like any other post-colonial society, is to notice its colonial burden and not be a slave to it.