Recently, I met a gentleman called Riyaz Ahmed, a Kannada translator, at Delhi Book Fair. As it happens with most of my conversations, this one, too, drifted towards literature. I was particularly interested in the kind of writing being done by contemporary Kannada authors. When I asked him about this, he responded with, “There is a lot of experimentation going on. New themes are being explored, fresh ideas are being shaped and executed, and writers are constantly pushing boundaries.” This spirit of innovation, he said, has never stopped in Kannada literature.

His words have stayed with me since then. So, when I picked up this book on classic Kannada short stories, a collection of translated short stories spanning nearly a century, I found his statement being reflected in its pages. The first modern Kannada short story was written in 1900, and ever since, the genre has been in a state of continuous evolution.

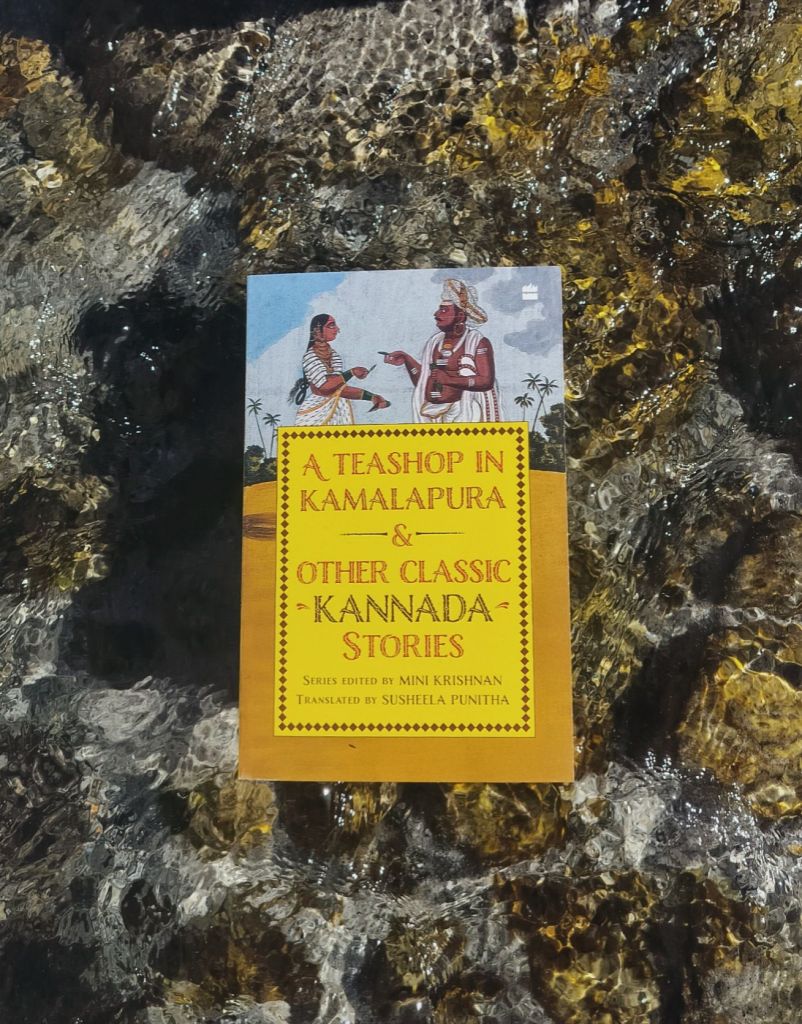

This anthology, translated into English by Susheela Punitha and edited by Mini Krishnan (whose collection of Malayalam short stories we discussed in an earlier post), follows a chronological arrangement of stories from 1900 to 1995. As always, I couldn’t help but trace the evolution of storytelling through these decades.

The opening story, At a Teashop in Kamalapura, is where the book derives its title. Written in 1900, it tells the story of a man who enjoys boasting in front of his friends, only to end up embarrassing himself. Knowing that this was the first modern Kannada short story, I expected it to be a product of its time—perhaps outdated in style or a little simplistic. But I was wrong. The story was full of humour, sharp dialogues, and a natural flow that felt strikingly modern. I found it brilliant.

The title of this story also got me thinking—why do we call them teashops in India when, especially in the South, they serve coffee frequently, as it was the case in the story? We never call them coffee shops. It made me wonder if India’s deep-rooted romance with tea has influenced our linguistic habits more than we realise.

One of the things I loved about this collection was its diversity—not just in themes but in the voices it represents. In the introduction, the translator mentions that she carefully selected stories from writers of different genders, religions, and social backgrounds. The result is a book that allows you to move swiftly through time and space, stepping into different worlds, some ancient, some pre-modern.

Journeying through emotions in Kannada

In one story, we laugh at the desperation of a young man eager to get married. In the next, we are confronted with the grim reality of a young girl married off to a deity, destined to live alone for life, occasionally sharing her bed with guests. This latter story, The Girl I Killed, is heart-wrenching. It exposes the cruelty of certain folk traditions when viewed through a modern lens. Some customs, though deeply rooted in history, clash violently with our modern ideals of justice and individual freedom. This was the tussle I found in the story.

Then there’s Two Ways of Living, a deceptively simple yet profoundly moving tale. At first, we follow a protagonist who seems to be a slave, enduring daily mistreatment from his master. As the story unfolds, we realise—through subtle clues—that the narrator is actually a horse, lamenting his life of servitude. The story delivers a powerful, thought-provoking message about the exploitation of animals, a theme that is perhaps even more relevant today.

The final story in the collection is another tragic one. It sheds light on the struggles of a Muslim woman who, after being divorced by her husband, is forced to return to her mother’s home. Instead of finding support, she is met with cold indifference and even cruelty. Her mother repeatedly reinforces the idea that women must accept suffering as their fate. This story shows the ways in which patriarchy is not just imposed by men but often internalised and perpetuated by women themselves.

Colonialism and the evolution of our languages and culture

Beyond the evolution of storytelling, what fascinated me was the transformation of language itself. The early stories have a certain raw, natural quality—rich in descriptions of nature and daily life, with dialogues that feel casual and unfiltered. As the years progress, the language becomes more refined, more intertwined with external influences. By the time we reach the later stories, we see Hindi proverbs entering the text. (So much about the Hindi-Kannada debate these days!) Phrases like putting ghee in fire (inciting someone) or where are you dying? (used when searching for someone) find their way into Kannada storytelling, reflecting the organic fusion of languages that happens over time.

Reading this book also sparked a somewhat controversial thought—one that I hesitated to write down. But here it is. Could there have been something positive about colonial influence on literature? I know it’s a sensitive question, but bear with me.

First of all, the short story as a format may not have evolved so significantly in Kannada literature without the exposure to Western literary traditions. Moreover, the themes explored by early writers suggest that renaissance, progressive, and modernist movements had a deep impact. Many of these stories directly critique social evils, demand reform, and challenge oppressive traditions. And isn’t that how societies evolve—by engaging with new ideas and questioning old ones?

This collection spans nearly a hundred years of Kannada storytelling, offering a unique experience filled with diverse plots, emotions, and social commentaries. It makes you reflect on Kannada society—how much has changed, and how much remains the same. If you love short stories, history, or simply enjoy seeing literature evolve across time, this book is for you.

Note: You can listen to our podcast featuring this book here.