Malayalam, a Dravidian language spoken predominantly in Kerala, has been there for over a millennium. However, the development of modern prose, particularly in the form of short story writing, emerged relatively late, gaining prominence only in the 19th century. This period marked a significant shift in Malayalam literature, influenced by both traditional storytelling and Western literary forms introduced through colonial interactions. It’s true that the short story format truly blossomed with the works of giants like Vaikom Muhammad Basheer and Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai (read our newsletter on Malayalam literature), the seeds were actually sown in the 19th century.

I had read the works of the writers mentioned earlier, but I was largely unfamiliar with the short story authors who preceded them. So, when I picked up this book of classic Malayalam stories, I discovered writers and tales that were previously unknown to me, adding to my limited understanding of the language’s literary heritage. The collection features the English translation of stories that were written in the late 19th century or early 20th century.

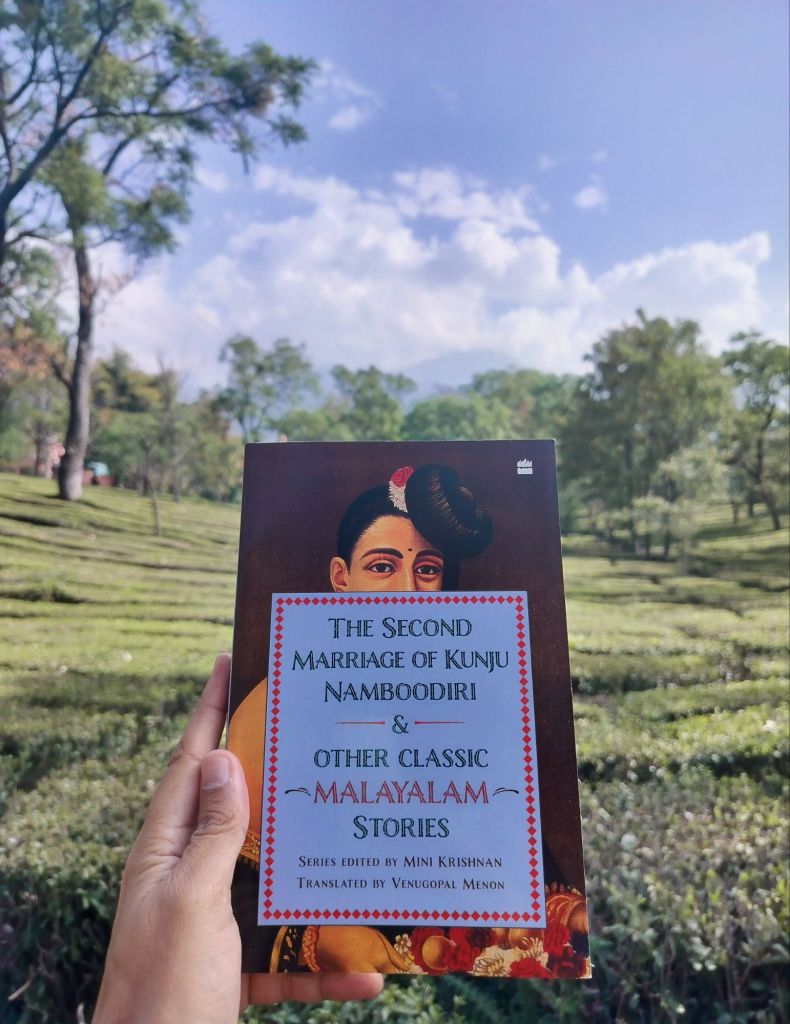

The book is called The Second Marriage of Kunju Namboodiri and Other Classic Malayalam Stories, so I’ll begin with the title story. “Namboodiri” refers to a traditional Malayali Brahmin community known for their priestly roles and land ownership, whose lives were governed by rigid social and religious norms.

The 20th century marked a significant period of social reform in Kerala, particularly within the Namboodiri community. Several other writers have also explored this topic, focusing especially on the challenges faced by Namboodiri women. One particular book, Antharjanam, is quite helpful to understand what it meant for a woman to grow up in a Namboodiri household.

In “The Second Marriage of Kunju Namboodiri,” the main character, Kunju, seeks a new alliance under the pretext that his current wife lacks both social status and wealth. What I found interesting was how brilliantly the morality of polygamy was portrayed in the story. Although polygamy was a norm in the community, some characters still saw the unfairness of it. What follows is a story you might have seen countless times in Indian movies: a man disrespects his wife and pursues another, only for tragedy to strike, after which his wife cares for him devotedly. This leads him to realise that she is the one for him, leading him to abandon his other plans. No, I am not suggesting that the author, Abhinava Chandu Menon, used this clichéd trope. On the contrary, I am saying that our movies have turned such classic stories into clichés.

One thing I noticed was how the short story format evolved in Malayalam literature from 1891 onwards, the year the first Malayalam short story was published. The story I’m referring to, “Instinctive Mischief,” has some ambiguity when it comes to authorship. It follows the reflections of a thief who complains about his inability to even do his job perfectly. Convinced that he lacks the skill for this profession, he resolves to go on a pilgrimage to Kashi. The narrative is straightforward, with little complexity in its plot. But that was just the starting point of the Malayalam short story.

Over the years, the Malayalam short story format has gained greater complexity and depth. It has explored a wider range of themes and witnessed increased experimentation. For example, a short story published in 1911, “Witless Women,” delves into the concept of gender equality, highlighting how women were perceived—even by the most prominent intellectuals of the time. As the years progress, satire emerges too. Take, for instance, the 1924 story “Cuni’s Remedy,” which mocks a popular Nature Therapy trend of that era. By 1930, the stories grow richer in substance, and from that point onward, writers like Basheer and Thakazhi take the form to new heights. (Note: The works of these two authors are not included in this particular collection.)

In some ways, these stories capture the world as it was back then, while in others, they mirror the reality of today’s society. Themes such as caste and religious traditions, corruption in the police force, and the brutality inflicted by Tipu Sultan on Hindus—a topic frequently discussed in today’s media—resonate through these narratives. One such story, “The Lifespan of Aissakutty Umma,” is a blend of fiction and historical reality. Though fictional, it is grounded in the historical context of Tipu Sultan’s invasion of Malabar, where he sought to dismantle the region’s native culture and identity.

These stories offer a wonderful opportunity to look at the past, while amusing ourselves at the same time. From casual husband-wife banter to a fantastical journey through the underwater city of Dwarka, they present a wide range of ideas. I’m sure you’ll enjoy reading them and, in the process, gain a deeper understanding of Kerala as it was a hundred years ago.

PS: If you’d like to listen to our podcast on this book, click here.