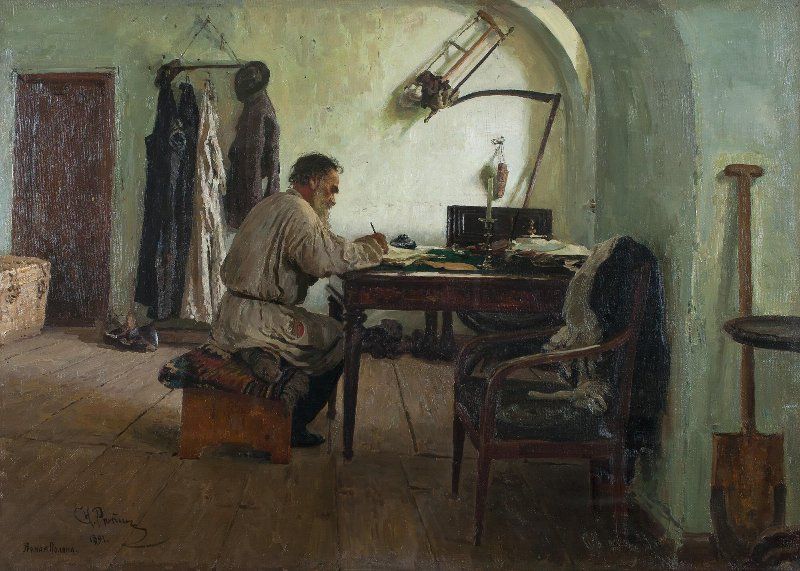

Leo Tolstoy’s A Confession is a short book, no longer than a Sunday afternoon, yet it contains questions so vast that they stretch across the entire human experience: Why should one live? What makes life meaningful? What stops us from killing ourselves?

It is a book written by a man standing at the edge of a deep internal precipice, and looking down without blinking. The narrative is personal, but its philosophical urgency belongs to anyone who has ever questioned the purpose of life.

The book is a philosophical exploration of these fundamental questions. However, Tolstoy does not offer clear answers. What he does, instead, is narrate the story of how he lost faith, how he lived without it, how he suffered because of it, and how he eventually rediscovered a form of belief — not through doctrines, but through the lives of ordinary people and a dream that illuminated what no argument could.

Let me take you through the narrative in A Confession, step by step, while exploring the philosophical questions that emerge along the way.

(For the sake of simplicity I am going to call the narrator of the book Tolstoy, though no specific name has been mentioned.)

A childhood baptised into faith, and a youth that abandoned it

Tolstoy begins where many spiritual autobiographies begin: in childhood. He was baptised in the Orthodox Church, taught prayers by elders, and absorbed the rituals without ever grasping their meaning. As a child, he believed easily. It is what children do. But by fifteen or sixteen, faith had already begun to retreat from him.

He abandoned the second course of university studies; more importantly, he abandoned belief. The religious teachings he had been given suddenly felt like fairy tales — implausible, irrelevant, intellectually unconvincing. Faith had not been wrestled with; it had merely evaporated.

This experience is not unique to Tolstoy. Many young people, especially those surrounded by our “educated society,” undergo a similar distancing. Tolstoy writes that in his circles, educated people did not believe in God or religion in any serious way. Open religious conviction was something to be laughed at. If a person pursued faith, they were mocked or labelled odd, almost socially defective.

Tolstoy absorbed this attitude. But he insists he was not entirely faithless. He believed in what he calls “perfecting oneself,” in self-improvement. He believed that life should be directed towards becoming better. And this, he acknowledges later, is also a kind of faith — the belief that there is something worth striving towards.

Pleasure, war, writing — and the collapse of intellectual authority

In his youth and early adulthood, Tolstoy threw himself into pleasure. He drank, gambled, pursued women. He fought in wars, killed people, and watched others die. These experiences did not restore faith — they merely distracted him from the question.

Later he became a writer, and entered the company of the intellectuals — the thinkers, the artists, the novelists. At first this world enthralled him. But as the years passed, he began to see that intellectual society had its own illusions.

He even describes these groups as a “lunatic asylum”:

Writers believed they were the teachers of humanity.

But what exactly were they teaching? They didn’t know.

They contradicted one another. They preached reform but lived decadently. They claimed to know the truth but rarely agreed on any truth at all.

If faith in religion had dissolved early, faith in the intellectual elite dissolved later.

Europe and the religion of progress

Tolstoy then travelled to Europe, expecting enlightenment. What he found was something he could not respect: an unexamined faith in progress. People believed they were advancing (in science, industry, society, etc.) but could not say where they were progressing to.

Progress was treated as a religion:

- unquestioned,

- assumed,

- directionless.

Tolstoy returned home disillusioned. He married, raised a family, worked in schools, and spent time among ordinary people. But beneath the surface, the philosophical disquiet remained.

The Crisis: the question that would not leave him alone

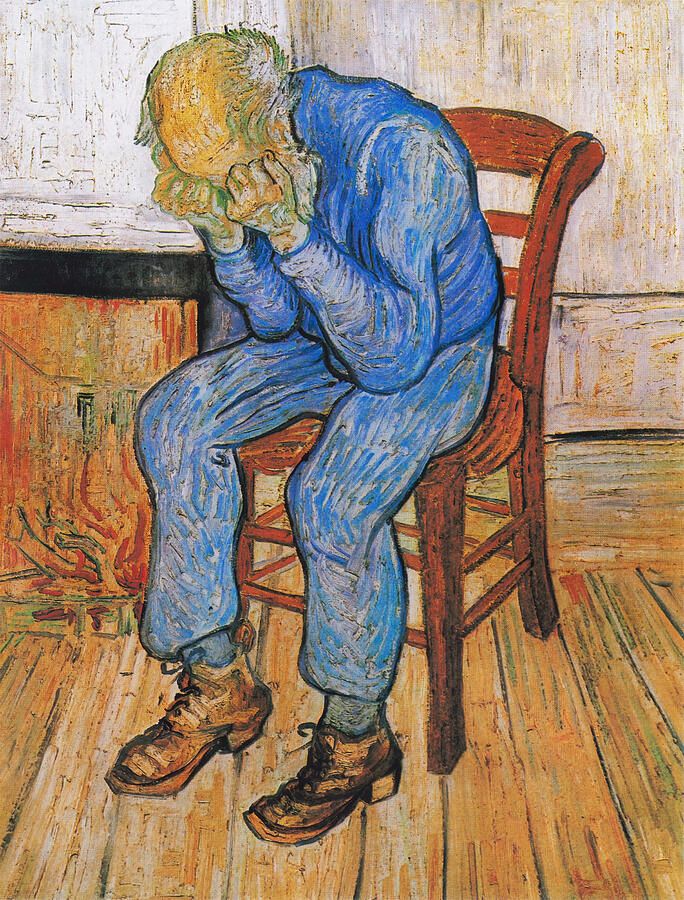

Then came a period he describes as an existential collapse.

What is the meaning of life?

Why do anything?

Why continue living?

He stopped being able to write. Hunting, a former pleasure, brought him no joy. He could not write much. He could not even distract himself meaningfully. What he feared most was suicide, because the thought had begun to follow him quietly, persistently, like a shadow.

Art, he concluded during this period, was merely an adornment to life — a decoration, not a foundation. And no decoration can sustain a collapsing structure.

Science — and its inadequacies

In search of answers, Tolstoy turned to science. But he soon realised that science could not provide what he sought.

He distinguishes two kinds of sciences:

(a) Experimental sciences — biology, physics, chemistry.

These describe the “how” of life, but never the “why.” They say nothing about meaning. They avoid the question entirely.

(b) Abstract sciences — metaphysics, theories of existence, philosophical systems.

These address the question, but give no meaningful answers. Their explanations were too removed from real suffering, too logical to help a man contemplating the pointlessness of living.

Science could tell him everything except why he should avoid suicide.

He returned from philosophy with the bleak answer offered by many thinkers:

Life is suffering, and the only reasonable action is to end it.

This conclusion horrified him.

The four ways people avoid the question

Tolstoy began to observe people around him, wondering how they lived without succumbing to despair. He concluded that people adopt one of four strategies:

1. Ignorance

They simply do not acknowledge the problem. They live as if life’s meaning does not need examination.

2. Epicureanism

They seek pleasure (food, wealth, comfort, distraction) and try not to think too much.

3. Suicide

Tolstoy argues this is the logical response of those who see no meaning and refuse to pretend otherwise.

4. Weakness

Those who see no meaning but lack the strength to end their lives, so they continue living out of habit.

He found himself between the third and fourth groups. He saw no meaning. But he did not kill himself.

This tension sustained his crisis.

Ordinary people — and the wisdom of living without philosophising

Tolstoy then turned to the lives of peasants and ordinary workers. These people woke early, worked hard, loved their families, observed simple rituals, and lived with steady faith. Their lives were filled not with abstract theories but with concrete meaning — however unsophisticated or superstitious.

He realised that intellectuals question meaning precisely because they stand too far from the fabric of life. Ordinary people remain embedded in life. They work, care, share, raise children, observe seasons.

Their knowledge is not rational; it is practical and emotional.

Their faith is not doctrinal; it is experiential.

Tolstoy admired this. He envied it. But he also recognised its limitations: their superstitions, their lack of intellectual clarity, their unquestioning acceptance.

Still, something in their way of living (something about their connection to labour, to community, to suffering, to death) began to restore in him a sense of meaning.

The Dream — Tolstoy’s turning point

Towards the end of A Confession, Tolstoy recounts a dream that becomes the symbolic climax of the entire book. This is what happens in the dream.

Tolstoy sees himself lying on a bed, on his back, feeling neither comfortable nor uncomfortable. He becomes aware of his legs and wonders how and on what he is lying. He notices that he lies on some kind of cords attached to the sides of the bed; his heels rest on one cord, his calves on another, and his legs feel awkward. He pushes away one of the cords at his feet (thinking it would relieve him), but this causes the next cord under his calves to slip. His legs begin to hang down; his body slips lower until his feet no longer touch the ground, and he is supported only by the upper part of his back. In terror he realises the height at which he is hanging — he cannot see the ground, only an abyss. Then he looks upwards into infinite space; and by looking up he feels calm. He notices beneath his middle there is one support (a cord) which holds him in balance; from it hangs a slender pillar at his head, though nothing visibly supports it. And in that configuration he lies securely. A voice seems to say, “See that you remember.” Then he awakes.

Now, let’s try to interpret the meaning of this dream.

The bed on cords, the slipping supports, the dangling legs — these images symbolise Tolstoy’s earlier existential crisis: he felt his life was unsupported, tenuous. He had removed the “supports” of old beliefs (rationalism, secular philosophy) and thus found himself dangling, suspended over something terrible (the abyss of meaninglessness). The cords slipping away reflect the loss of philosophical certainties and the danger of falling into despair.

What about the abyss, the height?

Tolstoy views life, when deprived of meaning or faith, as an abyss. His fear corresponds to his recognition that rational enquiry alone had led him to a dead end — he felt suspended between life and meaninglessness. The height emphasises the risk of the fall: his existential ground was gone, and he was aware of the possibility of collapse.

What does looking up mean?

In the dream, the shift happens when he stops focusing on the abyss beneath and instead looks upwards into “infinite space”. That represents the turn toward transcendence, faith, and the acceptance of something beyond rational scaffolding. It is the moment of transformation: the support he thought was missing he now realises is present, albeit in a form that reason cannot fully grasp.

Then there is a single loop under his body. This becomes the symbolic support he finds: not a multitude of cords (philosophies, arguments) but a single, simple support — metaphorically faith or spiritual anchoring. There is also a slender pillar at his head. The pillar and loop are inexplicable in rational terms (“though to one awake that mechanism has no sense”). But in the dream, their reality is revealed. This suggests Tolstoy’s conclusion: that one does not need multiple philosophical justifications once one finds the true support — the faith in life, in the divine.

The final phrase in the dream (“see that you remember”) indicates that this is not a mere dream but a reminder or revelation: Tolstoy must carry this insight into waking life. The dream encapsulates his entire search and points to what must remain with him: the truth of spiritual support beyond reason.