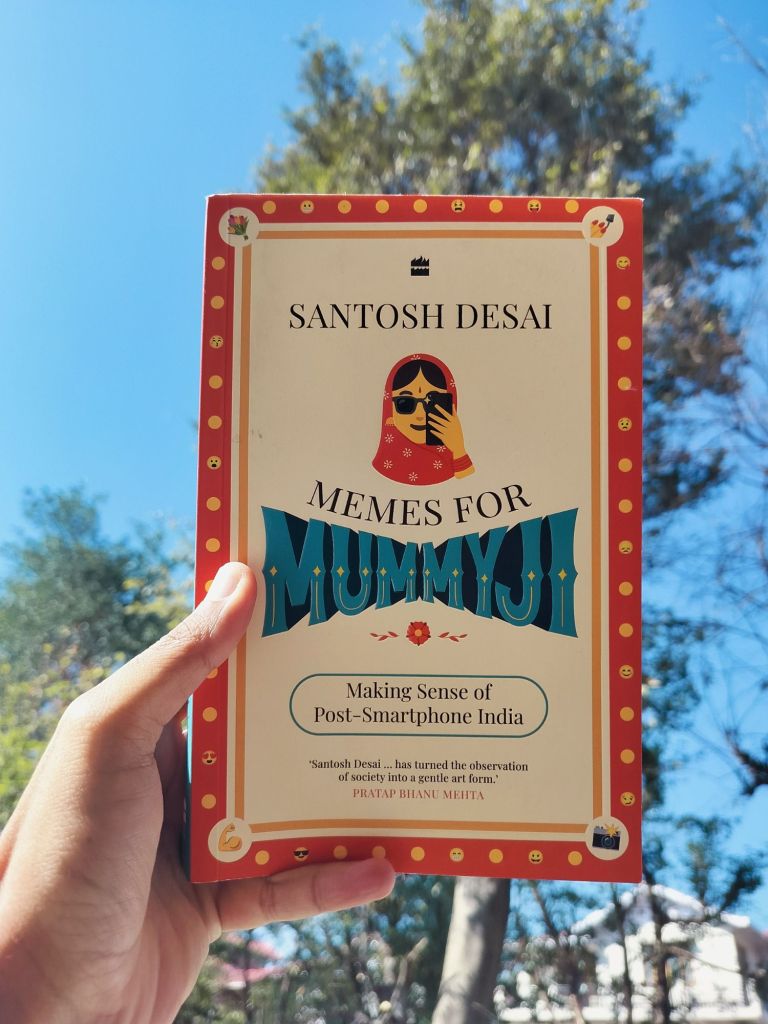

Memes for Mummyji: Making Sense of Post-Smartphone India by Santosh Desai is, as its subtitle suggests, an attempt to understand contemporary India, and unsurprisingly, the smartphone keeps returning to the conversation. This makes sense. Just as Desai repeatedly circles back to the phone, we too keep returning to it in life: to scroll, to react, to belong, to feel outraged, amused, validated. In some ways, the smartphone in the book functions not just as a device but also as a metaphor for how Indian society now thinks, feels, and performs itself.

The book itself is many things at once. It moves fluidly from musing to meditating, from philosophising to ranting. Structured into nine chapters, each containing several short pieces, the book feels closer to a curated collection of newspaper columns than a traditionally cohesive non-fiction work. There are over a hundred such pieces, each readable on its own, each addressing a particular idea, irritation, or cultural moment. This format makes the book highly accessible — you can dip in and out at will — but it also defines its limitations.

Desai’s range of interests is undeniably wide. He writes about memes, love, economics, nationalism, gender, geopolitics, advertising, aspiration, and everyday behaviour in post-smartphone India. If you enjoy reading a perceptive, occasionally exasperated observer trying to make sense of a rapidly changing country, there is much here to enjoy. The diversity of topics keeps the book lively, and Desai’s long experience as a cultural commentator gives him an instinctive feel for the zeitgeist.

That said, the very format that makes the book readable also prevents it from achieving greater depth. I feel that fewer pieces, written at greater length, might have allowed Desai to explore his ideas more fully. As a columnist, he appears most comfortable within the constraints of short-form opinion writing, but a book demands a different kind of architecture. Here, themes recur without being developed, arguments are revisited with only slight variation, and there is noticeable overlap across pieces. The book also lacks a strong narrative or conceptual build-up; it moves quickly from one subject to another, often before the previous idea has had time to settle.

At times, some observations come across as overly simplistic. For instance, when discussing men targeting women who speak up for feminist ideals, the analysis feels thin. Or consider the following sentence.

Growing up, falling in love was something that happened largely in movies.

Or this one.

The story of progress over the last few centuries has been that of separating human action from impulse.

Really? You’ll likely end up scratching your heads after reading such remarks, as did I.

In a better world, in order to make such points persuasive, the author could have leaned on storytelling, case studies, or empirical references. He does neither, and as a result, some arguments remain assertions rather than insights. The absence of depth is not due to lack of intelligence, but perhaps due to the self-imposed brevity of the column format.

Ultimately, Memes for Mummyji will appeal most to readers who enjoy cultural commentary in small doses — and who find a certain charm in what can feel like the rants of an ageing, articulate uncle lamenting how much India has changed, and how quickly. It is sharp, readable, often amusing, occasionally insightful, but rarely probing. As a snapshot of post-smartphone India, it captures the noise, speed, and fragmentation of the times. As a book, however, it leaves you wishing it paused longer, dug deeper, and trusted its own ideas enough to let them breathe.