There are writers who overwhelm you by sheer scale — vast novels, tangled ideas, large casts that feel like mobile cities. Dostoevsky is definitely one of them. Readers often hesitate before entering his world, imagining it to be dense, dark, almost suffocating. Yet the entry point into Dostoevsky doesn’t have to be his big books Crime and Punishment or The Brothers Karamazov. In fact, the best doorway is one of his shortest works: Notes from Underground (1864).

This slim, furious, fractured work contains (sometimes quietly, sometimes in full eruption) every major concern that defines Dostoevsky: the torment of consciousness, the struggle between freedom and determinism, the longing for dignity, the grotesque comedy of human self-destruction, and the painful search for meaning in a world that feels indifferent. Reading it is like standing at the mouth of a cave in which all of Dostoevsky’s later novels echo.

The Plot: A Man Against Himself

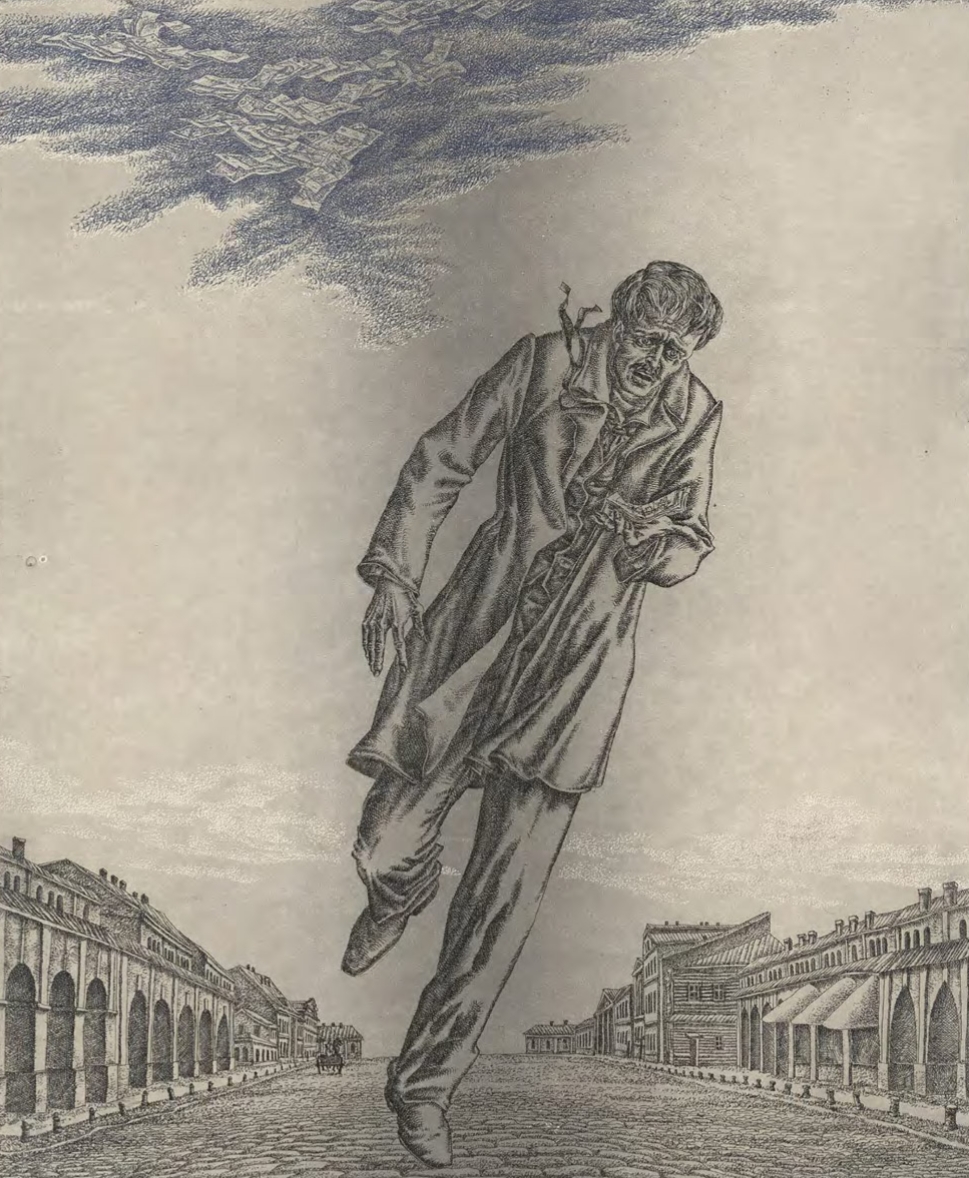

Notes from Underground is divided into two parts. The first, titled “Underground”, is a raging monologue by an unnamed narrator, known simply as the Underground Man. He is a retired civil servant in St Petersburg, a man who is intelligent, hyper-self-aware (sometimes to the point of being paranoid), and paralysed by his own thinking. He lives alone, resentful, suspicious, and perpetually at war with himself and with society.

This section has no plot in the conventional sense. It is a philosophical confession, an attempt by the Underground Man to explain why he is the way he is — why he sabotages his own happiness, why he finds pleasure in humiliation, why he distrusts all systems of reason. He attacks the “rational egoism” popular in his time, the idea that human beings will naturally choose what is best for themselves if only society becomes scientific and rational enough. He finds this notion absurd because, as he keeps reminding us, he himself knowingly chooses what destroys him.

The second part, “Apropos of the Wet Snow”, provides the narrative flesh to the philosophical skeleton. Here we see the Underground Man in action. He attends a dinner with former schoolmates whom he despises, forces himself into their company out of wounded pride, and ends up humiliating himself yet again. Afterwards, in a fit of emotional chaos, he follows a young sex worker named Liza to her room. There, in a moment of cruel clarity, he lectures her about the misery of her future, pretending to rescue her while ultimately breaking her spirit.

Later, when Liza comes to his shabby apartment seeking some human connection, the Underground Man is overwhelmed by shame. Instead of accepting kindness, he lashes out at her again, driving her away. Her exit is the emotional core of the book — an intimate scene in which Dostoevsky shows how a man can both long for love and be utterly incapable of receiving it.

The plot, though small in scale, is like a laboratory for Dostoevskian psychology. Every humiliation, every hesitation, and every implosion of pride is a demonstration of ideas that will later explode across his major novels.

Why this book is the best starting point for Dostoevsky

It is Dostoevsky in miniature.

The tensions that animate Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, Demons, and The Brothers Karamazov are all present here, but they are more concentrated, more raw. Notes from Underground is the blueprint.

It is psychologically immediate.

Dostoevsky’s longer works can take hundreds of pages to build psychological pressure. Here, the pressure is immediate. From the first page itself, we are inside a mind that is both brilliant and broken. Dostoevsky wastes no time: the contradictions, the self-laceration, the grotesque humour — everything arrives at once.

It is a critique of modernity that still feels new.

Western rationalism, scientific utopianism, the dream of perfect societies — Dostoevsky sensed the dangers of these ideas long before the twentieth century witnessed them in reality. In Notes from Underground, he argues that human beings will always resist any system that tries to predict or mechanise them. This argument becomes crucial for understanding Russian literature, existentialism, and even modern psychology.

It teaches you how to read Dostoevsky.

Dostoevsky’s narrators cannot be trusted. His characters exaggerate their own emotions. His moral points emerge through contradiction rather than clarity. Notes from Underground trains you in this method. After reading it, one learns not to take anything in Dostoevsky at face value.

The philosophical core

The war against reason

The Underground Man insists that reason is too narrow to contain human behaviour. If reason tells us to pursue our own welfare, why do we repeatedly choose suffering? Why do we reject improvement? Why do we take a perverse delight in acts that harm us?

His answer is freedom.

Human beings, he argues, will accept suffering as long as it allows them to assert their individuality:

One’s own free and unfettered volition, one’s own caprice, however wild, one’s own fancy, inflamed sometimes to the point of madness — that is the one best and greatest good, which is never taken into consideration because it cannot fit into any classification and the omission of which sends all systems and theories to the devil.

This becomes one of Dostoevsky’s shaping ideas: the notion that freedom is so fundamental that people will destroy themselves just to prove that they are free.

The illusion of rational progress

In the nineteenth century, there was a growing belief that science would solve human irrationality. Society would become predictable. People would behave reasonably. Happiness could be engineered. The Underground Man mocks this vision. He calls it a “crystal palace” — a beautiful structure in which human beings would be imprisoned by perfection.

This criticism anticipates later existentialists like Sartre and Camus. It also provides a counter-voice to the optimism of early modernity. Dostoevsky suggests that any system promising universal happiness must ignore the stubborn messiness of human nature.

Awareness as curse

Perhaps the most painful idea in the book is that self-awareness, usually considered a virtue, becomes unbearable when intensified. The Underground Man feels everything too sharply. Every insult, every slight, every imagined humiliation becomes magnified under the microscope of his mind.

Dostoevsky shows that consciousness without purpose, faith, connection, or love becomes a trap. It eats itself. It turns intelligence into acid. This idea resonates throughout his mature novels — Raskolnikov, Ivan Karamazov, and Stavrogin are all men destroyed by an excess of thought.

The human need for connection

The encounter with Liza is the emotional heart of the book. She represents the possibility of tenderness, something the Underground Man desires but cannot accept.

When Liza comes to him, vulnerable, searching for comfort, he panics. He knows what to do in theory (be kind, be open, be gentle) but this knowledge becomes another weapon against himself. Instead of choosing connection, he chooses cruelty. What Dostoevsky shows here is that the greatest tragedies are not battles between good and evil, but failures of the human heart at the moment it is called to act.

What the book ultimately reveals

Notes from Underground is not a story about a man alone; it is a story about the human condition in its most intense form. The Underground Man is what we become when our intelligence is severed from compassion, when our desire for dignity turns inward, when our freedom loses its ethical grounding.

And this is why the book remains such an excellent introduction to Dostoevsky. It prepares the reader for his larger world, a world where characters are torn apart by ideas, where philosophy becomes drama, where the deepest battles are internal. Once you have lived in the claustrophobic, echoing space of the Underground Man’s mind, you are ready for Raskolnikov’s fever, Prince Myshkin’s purity, Ivan Karamazov’s rebellion, and Alyosha’s faith.

To begin with Notes from Underground is to begin with the key to Dostoevsky’s universe. It is a short book, but inside it lie all the questions that make Dostoevsky one of the greatest explorers of the human soul: What does it mean to be free? Why do we harm ourselves? What is dignity? Can consciousness bear the weight of itself? And how do we learn to love, when love requires giving up the very defences that keep us safe?

Every one of Dostoevsky’s novels is an attempt to answer these questions. Notes from Underground is where they are asked with the greatest rawness. And that is why, for any reader stepping into Dostoevsky’s world for the first time, this is the perfect place to begin.