Milan Kundera raises several philosophical questions in his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being. He begins the novel with a reflection on Nietzsche’s idea of eternal recurrence. Nietzsche imagines a world in which everything returns endlessly, where each moment must be lived again and again for eternity. Kundera, however, approaches it from the opposite side: by asking what it would mean if life did not return. He writes:

“The myth of eternal return states that a life which disappears once and for all, which does not return, is like a shadow, without weight, dead in advance, and whether it was horrible, beautiful, or sublime, its horror, sublimity, and beauty mean nothing.”

According to Kundera, there are two ways of looking at existence. One is Nietzsche’s vision of heaviness, in which everything recurs infinitely. Here, each choice carries the unbearable weight of responsibility: every word, every gesture nailed to eternity. Imagine reading this same passage not once or twice, but an infinite number of times. And not just reading this passage, every single moment of your life, it keeps on repeating infinitely. That is the heaviest of burdens, according to Nietzsche. Yet, this weight also brings depth and meaning, because what recurs must matter.

The other view is that of lightness, which seems more plausible when we look at our lives. “You don’t enter the same river twice,” said the great Japanese writer Kamo no Chomei. In such a world where each moment happens only once, you are free of burden, free of responsibility. This freedom, however, comes at a price. If things happen only once and vanish forever, they carry no lasting meaning. A fleeting affair, a conversation overheard, a decision never to be repeated. It is light in consequence, but also empty.

So where does one stand? Should we embrace freedom, or accept responsibility? If these questions feel too philosophical, Kundera grounds them in the story of Tomas, a neurosurgeon whose life becomes the stage for this philosophical struggle.

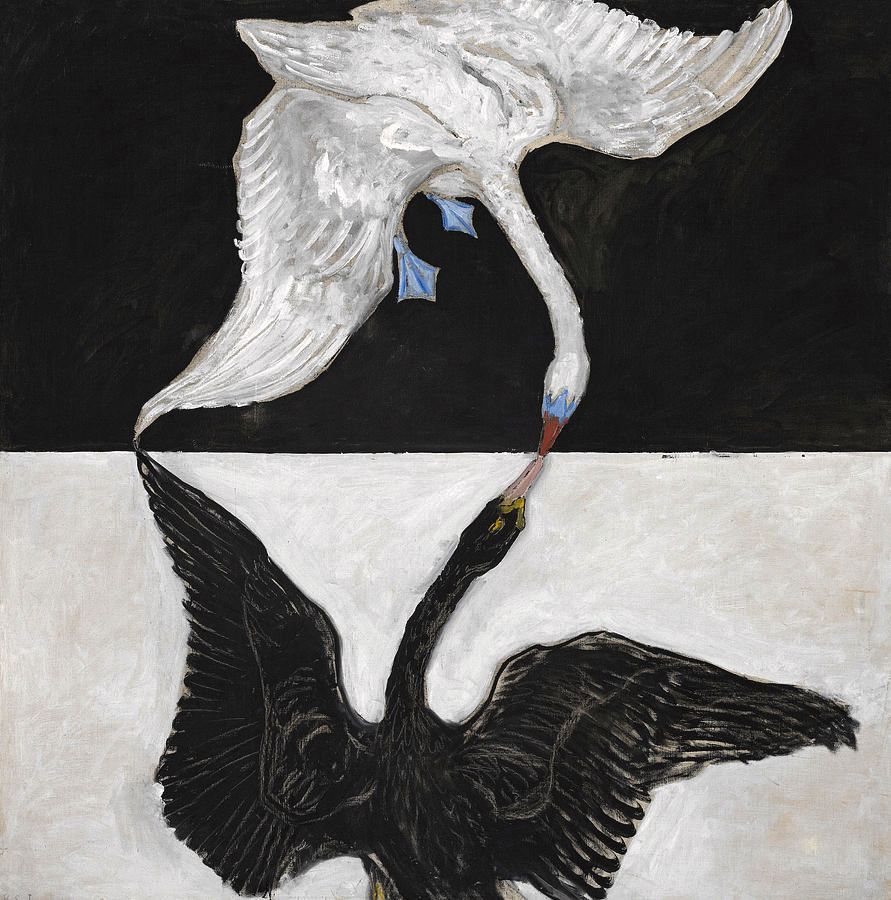

Tomas loves Tereza, but he also seeks affairs, most significantly with Sabina. Each woman embodies one pole of Kundera’s opposition: Tereza, the heaviness of love and responsibility; Sabina, the lightness of freedom and sensuality. Through Tomas, Kundera shows how we are caught between these two forces, longing for both and suffering under both.

The suffering of lightness

Before meeting Tereza, Tomas lived what he thought was a free life (lightness, as we’ve been calling it). He created a system of “erotic friendships” where intimacy was stripped of sentiment and commitment. “The only relationship that can make both partners happy,” he told his mistresses, “is one in which sentimentality has no place and neither partner makes any claim on the life and freedom of the other.” And yet, despite this carefully built framework, Tomas felt an emptiness. His affairs provided pleasure but not meaning. Think of a beautiful meal that leaves you hungry an hour later. Lightness, he discovers, is not so light after all.

The suffering of heaviness

Tereza brings depth and tenderness into Tomas’s life. But with love comes responsibility: explanations, apologies, defences against jealousy, endless negotiations of trust. Tomas is weighed down by her suffering and his own guilt. Love gives his life beauty, yet it also exhausts him. Responsibility, as Kundera suggests, is never without its fatigue.

The paradox of lightness and heaviness

Most of us live where Tomas does: between freedom and burden, between lightness and weight. We long to be free when we feel trapped in commitment, and long for commitment when we feel the loneliness of freedom. I think we can relate with the way someone envies their single friends while in a marriage, and yet envies married friends when he is single. Tomas, too, cannot resolve the tension. He continues his affairs with Sabina but refuses to abandon Tereza, even when history itself (political upheaval, war, Russian tanks making their way as they so often do) makes this balance unsustainable.

This is the heart of Kundera’s opening meditation. We suffer under both lightness and heaviness, yet we are irresistibly drawn to each in turn. Human life unfolds in this paradox: a restless oscillation between freedom and meaning, between the unbearable lightness of being and the inescapable weight of existence.

As I said in the beginning, there are several other philosophical ideas in the book. I will discuss them in the upcoming posts.