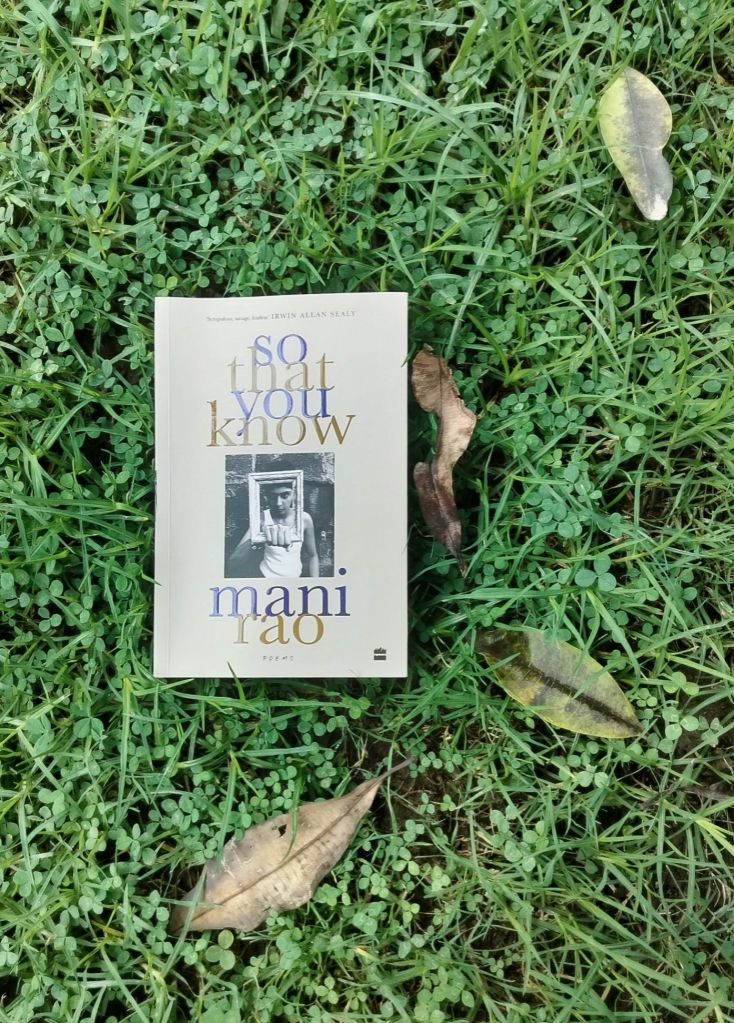

Just the other day, I was rereading Rudyard Kipling’s If, a grand poem about becoming a man by mastering fate, time, loss, and victory. In other words, a checklist for stoic masculinity. And then I picked up So That You Know by Mani Rao, and something entirely different stirred within me. This poetry collection doesn’t speak in grandiose themes. Instead, it offers something quieter, subtler: a deep gaze into the tender, almost-invisible moments of life. The ones we often ignore. The ones that, when noticed and preserved in art, can stretch into eternity.

Now, let me state the obvious: explaining a poem is a bit like explaining a joke. It often kills the magic. And yet, it’s a sin I happily indulge in, because… let’s just say I love it. So here’s my attempt to talk about the poems in So That You Know, knowing fully well that they work best when read alone, slowly, in silence.

This is a book of gentle observations — of ordinary moments, childhood memories, 3:33 am musings, and of days spent yearning for something unnamed. But let’s not be fooled by the softness of the themes. Mani Rao writes with a quiet precision that strikes the right chord. There is an unmistakable feminine gaze in these poems, not in a loud or didactic way, but in the way they observe the world with empathy, detail, and a certain emotional honesty. Her poems are often set in modern, urban settings (though they frequently travel in time and space), but place is never the point. The poems are more about what it feels like to be human inside that place.

Now, let me share some of my favourite verses from the book and discuss them here.

Turning memory into myth

The first poem in the collection is titled Did I Mention. This is how it goes:

Did I mention how I see us

Heads too large for our child bodies

Mouth-buds, wide-set eyes

Like Charlie Brown and Lucy

Walking, blowing

Soap bubbles, speech blurbs

Who’s buried under the memory tree

What’s the name of the bird in that nest

Tell no one how old we are

Or that we know Chiquitita by heart

I loved the imagery here: heads too large for our child bodies. The two characters appear like cartoonish figures. One can notice how Rao is subtly commenting on disproportion, fragility, and how identity, whether acquired or imposed in childhood, stays with us. She frequently returns to the past throughout the book, selecting memories and preserving them like artefacts. Isn’t that what you would call myth-making? Interestingly, some of the poems also transport you into the world of myths: Indian, Greek, or even Roman.

Are spaces metaphysical traps?

Many of the poems in the collection reimagine the places, both as a literal space and as metaphor. This is especially evident in the poem titled This Marriage and its sequel, That Marriage.

Let’s take a closer look. First, This Marriage.

It’s not too cold, I know,

but I had nowhere else

to keep this overcoat

All my suitcases were full

And my closet overcrowded

So I just let it sit

upon my shoulders

You can see how the metaphors unfold here. Nowhere else to keep the overcoat, because the suitcases were full? So just let it rest on the shoulders? Of course, she’s not really talking about an overcoat or suitcases. This is about responsibility (the weight of marriage and relationship) and how one carries it, despite its burden. So, here, objects are being mapped on to emotional states. What about That Marriage? Let’s read that too.

A haunted house

afraid to die

Echoes fold

Should the poem end there

The Happy Prince returns

on the radio

‘Swallow, little swallow, will you not

stay with me one night longer’

Just notice how the space metamorphoses into emotion itself. The house (again a metaphor) becomes haunted by memory and stagnation. Somehow, to me, it felt like a reimagining of Virginia Woolf’s idea of A Room of One’s Own, except here, the room is not chosen, not empowering, but quite suffocating. There is a sense of emotional paralysis of a failed relationship. And yet, it lingers, as suggested through The Happy Prince’s reference, ‘for one night longer.‘

A feminine gaze

As I said earlier, throughout the book, you’ll get to see the world through a feminine gaze. Let me explain that with the help of a few examples.

In My Old Woman, Rao gently confronts ideas often omitted from our polite discourse: the leaking body, the aging woman, the grotesque inheritance of womanhood. “When death fell asleep between my legs,” she writes, a line quite charged with ambiguity when you think about it. Is it a metaphor for menstruation, menopause, stillbirth, or something else? I kept wondering but could not find an answer. Maybe the ambiguity itself was the answer. There’s also a kind of weariness in this poem, an emotional archaeology of what women inherit. It’s not always the beauty or wealth, but also burden and fatigue. It makes you think, doesn’t it?

Then Poem for a Librarian shows the poet’s skill at making the mundane mischievous. And while doing so, she brilliantly captures how misunderstood a woman remains to a man. The poem shows a librarian’s confusion over which shelf to place a book called Female (Feminism? Psychology? Poetry?), and in the end, he goes with Politics. It pokes fun at how we mislabel, misplace, and reduce the complexity of lives into bureaucratic categories.

I could go on with these examples, and still might not fully explain what I truly mean by the feminine gaze. But you’ll feel it, that much I can promise. You read Rao’s poems and begin to understand how a woman sees the world.

Final thoughts on the book

Mani Rao’s language is so condensed, so crisp, that it reminded me of Nietzsche’s desire to say in a few sentences what others need a book for. Take a look at the below verse called Pathetic Fallacy.

Sunset sky

Youth gone

Passion lingers

Just like the above example, Rao’s poems often end mid-thought or in silence, as if stepping back to let the unsaid bloom. These pauses speak louder than words. They leave you wondering, they leave you wanting for more.

There’s another thing I noticed when I read these poems. Many reviews and the book’s own blurb have highlighted the playful exuberance in Mani Rao’s work. And yes, it’s there. But what struck me more was an undercurrent of pain that runs through the book. It’s never dramatic or loud. But it’s very much there in the words that were said and that were not, or the way a memory returns at an unexpected moment, or in the quiet imagining of what could have been. I guess, it’s this feeling of pain is what gives the poems depth. It’s the kind of pain that doesn’t break you; it only reminds you of everything you’ve ever lost or could not find. And in doing so, it allows healing.

I must confess, I haven’t finished the book yet. It might take me a few months—and that’s okay. This is a collection to read slowly. To reread. To return to.

So that you know… you are not alone.

Note: I recently narrated some of these poems on my podcast. You can listen to it here.