Before reading Anuradha Ghosh’s recently published book Jamini Roy: A Painter Who Revisited the Roots, I had limited understanding of this maestro’s art. He was a captivating figure in 20th-century Indian art who broke away from traditional Western styles to create a vibrant world bursting with colour and life. But how did he get there? How did his style evolve? Thankfully, the book provides all these answers.

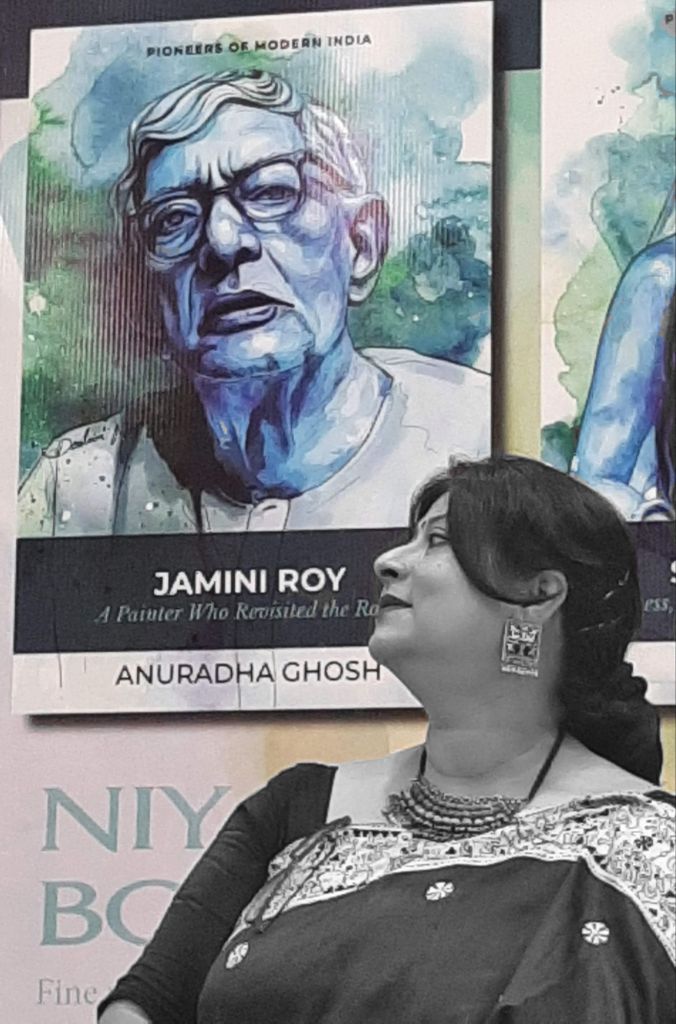

Anuradha Ghosh, the author behind this fascinating read, deserves immense credit. Her expertise and passion for art shine through every meticulously crafted sentence. The book also reveals a deep interest of the author in aesthetics, particularly Indian aesthetics. Her writing is eloquent, making the book feel like an engaging exploration of the subject. That’s the reason I really wanted to speak with her–and fortunately I got a chance too.

Below is the text of our exchange. It’s a long conversation, but I am sure that you would enjoy this masterclass by Anuradha Ghosh.

Deepak: Before we talk about your book, I want to start with your journey. Because the first thought that came to my mind when I started reading you book was, “Wow, the author has got such a beautiful understanding of aesthetics.” Could you tell me more about your own interest in art and aesthetics and how you have pursued it?

Anuradha: My love for art developed when I was very young. My father was a university professor, and we had a sizeable library at home. In it I once discovered a book called ‘The Outline of Art’, which was chiefly about European art and had a number of glossy plates of paintings. I spent hours admiring them, and also tried to copy them ineptly in my school exercise books! The first-ever prize I got in school, in class 1, was for a painting which I cannot even recall now.

Jamini Roy was a household name then, and my parents showed me plates of his paintings, as also the enigmatic paintings of Rabindranath Tagore. I also remember conversations at home connecting Tagore’s art with his poems and plays, and my mother, a fine singer, opened my eyes to the deep, mysterious ambivalence in both his art and music.

A little later, I had a Lalit Kala print of Prabhakar Barwe’s painting ‘The Blue Cloud’ in my room. It was unframed, stuck on the bare wall just like that. But I cannot even begin to explain how it affected me. It was possibly my first encounter with abstraction, and it felt as if I was set free. I was both driven and calmed by it. It was in my last year of school when I played truant and went off the visit a show of Picasso’s graphics which had travelled to Kolkata and was being shown at Birla Academy. At around the same time—a little earlier perhaps—My father took me to the landmark exhibition called ‘Visions’, which was my first introduction to the art of Jogen Chowdhury, Bikash Bhattacharjee, Ganesh Pyne and Somenath Hore. I was so overcome that I could not speak a word even after returning home.

And then Presidency College happened to me, which was like a whirlwind that undid me and shaped me anew. One hour I was being goosebumped with Shakespeare’s sonnets in class, and in the next arguing about Les Fleurs du Mal or maybe Anselm Kiefer’s paintings in the canteen. And it was in one of these stormy sessions that I met my future husband, who was an art student then, and had come over to Presidency to judge the art event in our annual fest, ‘Milieu’. And my fate was sealed.

We have been married for 27 years now, and we lead a very unconventional life. For us, it is working together that has always been the mainstay—this may sound boring, but is actually extremely exhilarating. I observe his painting process closely. He listens carefully to every line I write. I began seriously writing on art about five years into my marriage, and my first major book came in 2016, though there were others before that, including three volumes of poetry. I have participated in art camps and workshops as a theoretician as well. The one I still remember an ASEAN art workshop which I mentored—during its course, while speaking on Jamini Roy, I asked all the participants of different nations to paint folk motifs from their culture on a single canvas on which I had already painted Roy’s signature motifs from the alpana (floor art) of Bengal. It was an energized, charged moment that cannot be replicated or defined.

I am in search of these elusive moments. In art, and in life too.

Deepak: Let’s come to your books. Could you take us through your works?

Anuradha: My first major book was on Hemendranath Mazumdar, and before that, I had co-written a smallish book on Nandalal Bose’s collages. ‘The Afterlife of Silence’, the book on the still life of Jogen Chowdhury, came after this, and then the one on Jamini Roy. If you look closely, you’d possibly detect a similarity between Jamini Roy and Jogen Chowdhury with respect to the firm connection both their works have with the located culture of Bengal.

I have already mentioned my early attraction towards Jogen-da’s paintings, which had endured and become stronger with passing time. When I teach my class of students on modernist aesthetics, I rarely fail to mention how still life is inextricably linked to the evolution of Western modern art, and I had always been surprised at the dearth of books dealing with this genre. And I had gradually got to know Jogen-da better, followed most of his shows, and I felt his still lifes have a narrative about them which needs to be decoded. This would help us to relate to his other major works far more intensively. And that is how it all started—Jogen-da helped me a lot, let me have more than 200 images of his still lifes, even very old ones. I cannot describe what those few months were like—it was more of a meditative journey for me when the daily business, my household, my social circle, seemed like inessentials.

Jamini Roy, however, was a book I was commissioned to write, by Nirmal Kanti Bhattacharjee of Niyogi Books, whom I hold in very high regard. I was thankful for his trust in me. I have already mentioned about the specific interest about Roy that I had acquired very early in my life. The dark days of the lockdown were upon us then, and this assignment allayed some of the fear and insecurity of those days. I read practically everything that had been written on Jamini Roy, thanks to my father’s library, and academics, researchers, gallery-owners who sent me uncounted pdfs of books and articles I couldn’t access then. But the book took its own shape. I could actually see, and emotionally connect to, Roy’s solitary journey during those rich yet troubled times, and that is why I think there is an instinctive element in this book which has precious little to do with the extensive research I had undertaken. The researcher splits hairs and the creative writer brings it all together holistically: I’d say there’s a bit of both in the writing of this book.

Deepak: You start your book on Jamini Roy with the chapter Locating Identity. How big a factor, in your view, identity plays in an artist’s life. And if that’s the case, how do they ultimately transcend it?

Anuradha: For me, identity is an honest connection not only to the roots, but also to the branches. To both being and becoming, and the ever-changing dialogue between the two. If identity is the impress of the subjectivised self on one’s work, then this is what sets one apart, for no individual’s journey is like any other. For a creative artist, each line, each dab of colour, each element bears the narrative of a point in her/his journey. It is a coiled kind of history, really—histories, in fact, both emotional and social, that collude or collide. And then there is change. Things grow and things decay. We walk out of our favourite room and enter another, and allow it to define us. So the location of identity is a very difficult thing to map, and is absolutely, totally unfixable. In Jogen-da’s works we have seen this clearly, as in many others as well. A huge part of identity is the connection to one’s located culture, but culture itself is infirm and unstable in our own times. Thus as you see, your question has many answers. I’d say we should be looking for non-singular identities, and so should our artists. And as for transcendence, it possibly means much more than simply the movement from local to global. It may simply mean the breaking of shackles of one’s own ‘established’ identity, like Abanindranath did in his kutum-katam sculptures, or Nandalal Bose in his collages, an area of free play, where the moves transcend the rules of the game. Having said this, I’d say the ‘identity’ of Jamini Roy that I’ve written about in the first chapter traces both the roots and the branches, his adoption of the folk idiom and its very idiosyncratic transformation. You could see it as an attempt to trace the intersection of the unchanging, enduring quality of the folk and the rapid transformation of Roy’s universe of ideas and surrounds. I have also wondered, at times, whether Roy got somewhat confined within this circle of ‘identity’.

Deepak: Now that you have written and published this book, where would you place Jamini Roy in terms of his style?

Anuradha: My first response would be that, Roy is by far the most popular artist of Bengal, and this popularity often clouds his art historical estimation. His style had no successors, thus it is an islanded space, so to speak, the value of which is increasing even in our own times. His style has been borrowed in the field of decorative art, in couture. More people live with his art than any other. Fakes abound, in fact whole exhibitions have been mounted with fakes of Roy. For me this stylistic social connect is extremely significant, possibly because it is so rare. I’d say the uniqueness of his style cannot, and should not, be easily assimilated within the grand narrative of Indian art history. His stylistics should be studied as that inscribed space that branches out, stands apart historically. Our mainstreaming tendencies should spare his work.

Deepak: I am really curious to know about how you went about this project. Could you break down the process?

Anuradha: As I said, I began work on this book during the dark days of the lockdown. To begin with, I got together as many images of Roy’s paintings as I could find, and just observed them, for hours on end. I tried to imagine his life like a play, in episodes and empty intervening spaces, and tried to fill up the blanks with imaginative probability. Then came the actual research—collating facts, events, creating my own timeline rather than depending on existing biographies. I was keen on discerning the voice/s through which his paintings speak to us in this day, when everything has changed so much, including our ways of appreciating art. I saw him historically, but also somewhat like a contemporary; and I think it is this element of empathy that has made all the difference. You will notice I have used word-images abundantly, with the express purpose that the readers could ‘see’ him, and not only his paintings. The chapter division was also not easy to fix. I decided not to go along the temporal subdivisions that most biographies employ, but use the most important idealist/intellectual elements that define his life and career. Most importantly, I tried to make sure that the readers could connect to that moment of tranquil silence, of meditative submergence, which the best works of Roy never fail to bring to me.

Deepak: Could you share some of your favourite works of Jamini Roy and your perspective on them?

Anuradha: There are so many, but I’ll mention some. The painting titled ‘Nayika from Kalighat’ is an amazing work not only because it clearly shows us how Roy drew from Kalighat paintings, but because it helps to unfold not only the similarity of the two styles, but also their difference, almost like a subtext. The way Roy breaks up the ‘Kalighat’ line—the one that was traditionally used by the patuas as a single, plump contour line with a loaded brush—into un-graded, separate areas of colour is distinctly innovational. I am also especially taken by his ink-on-paper sketches, with comparatively faster movement of lines, possibly because these are so very different from his usually premeditated lines. I remember a number of such sketches named ‘The Holy Family’. And of course the Christ paintings too, including ‘The Last Supper’, with its interesting mix of Christian iconography with the style of regional folk. I am also intrigued by those faces which have eyes with their irises missing. I have tried to connect them with the traditional ‘Chakshudan-pat’, but could not discover any significant connection with any implied absence of sight, real or metaphorical.

Deepak: Should we expect another painter in your future books?

Anuradha: Hopefully so, if I manage to get enough respite to plan one. I am writing too much now, by way of academic articles and exhibition reviews. But I do have a plan to write a comprehensive book on abstraction in Bengal artists, but it would need a lot of planning and at least a year of research and studio visits. I have always wanted to work on Tagore’s paintings, and I observe his works closely whenever I have time. But this too would be a big project, and would involve an extended leave from my workplace. But if the logistics fall into place, I’m sure you’d see it soon!

Deepak: One question that I like to ask every author: what do you enjoy reading the most?

Anuradha: Poetry, anyday! I love Sylvia Plath—she shakes and moves me. Adrienne Rich is another favourite. But my dream time would be curling up with a volume of Bangla poems by Shakti Chattopadhyay on a rainy day. The novels of Ian McEwan when I’m in the mood, or the travelogues of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay—these usually sort out my leisure (which is in short supply nowadays). And yes, a recipe book by Leela Majumdar called Rannar Boi gifted by my mother many years ago is one that I have read at least a hundred times—it is an old classic that doesn’t age, doesn’t fade, and is oddly fulfilling; it’s more literature than a culinary book!