If you follow the news, you would have read quite a lot about the ongoing conflict in Manipur. In fact, it is in this context that most of the Indians know about Meitei and Kuki tribes. That was the first thought in my mind when I picked a book about Heisnam Sabitri, a phenomenal theatre artist belonging to a Meitei family.

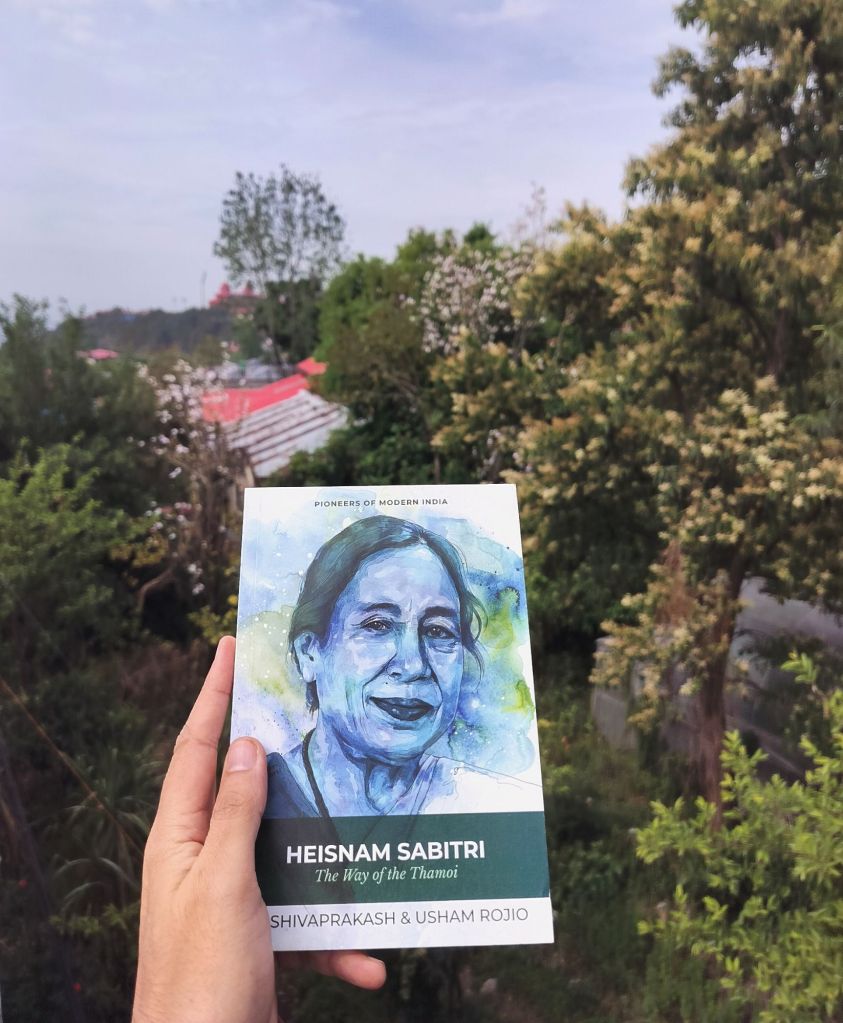

All right, enough of identity politics, let me tell you about the book. Heisnam Sabitri: The Way of the Thamoi is a monograph written by HS Shivaprakash and Usham Rojio.

Heisnam Sabitri: A brief introduction

Born in a small village near Imphal (Manipur) in 1946, Sabitri was initiated quite early to the world of theatre. She was about seven when her aunt, Chirom Ningol Gouramani, discovered the inner endowment of an artist in her. Gouramani was already a professional actress. Later, around 1953-54, she took Sabitri to Imphal and trained her.

In 1961, a group of students who were studying in Allahabad approached Sabitri to act in their play Layeng Ahanba (First Treatment). The play was written and directed by Heisnam Kanhailal. This was the first time they worked together, a partnership that will continue in both professional and personal world. One of the enjoyable scenes in the book is the elopement episode of the two lovers. Here is how it goes:

Kanhailal took his elder brother’s bicycle on the pretext of collecting his certificate for the course of typing. Instead, he mortgaged the bicycle and hired a mini truck. Kanhailal reached Mayang Imphal in the evening. He sent a friend to call out Sabitri. Sabitri came out of her house. Then, they eloped together on the mini truck, Hawadoz. They reached Imphal around 8 pm.

Heisnam Sabitri: The Way of the Thamoi

The beginnings of a new theatre

In the 1960s and 70s, a significant political shift was taking place in Manipur. After spending two decades demanding the full statehood and getting it in 1972, people were gradually realising their own historical position, their own problems, their own existential predicaments. The insurgency and counter-insurgency released a dynamics of violence, terrorism and corruption.

In such a difficult time, the world of theatre came forward to face the challenge. Led by theatre persons like Kanhailal, Sri Biren, W Kamini, Lokendra Arambam, and a host of other artistes started questioning on stage the authenticity of their own political and cultural life, and the meaning of their existence in absence of an identity.

Out of the socio-economic political situation of the early 70s, Sabitri-Kanhailal’s most outstand production was Tamnalai (The Haunting Spirit), which dealt with the theme of the problem of goons in the society and how the innocents suffered at their hands. This play was breakthrough in the art of writing drama, as well as in terms of the performance style in Manipur, which was otherwise bound to a long habit of writing plays in a linear style and on hackneyed themes.

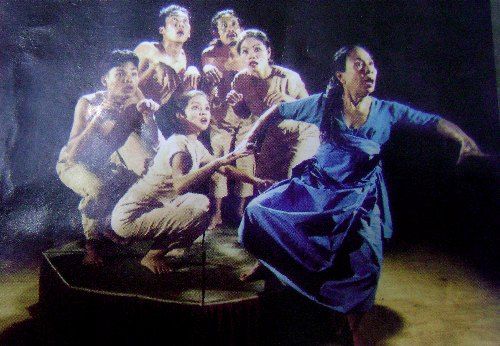

Giving voice to Body-Breath-Spirit

Sabitri-Kanhailal theatre, founded by the husband and wife duo, offered a unique approach that differed from both Western and traditional Indian theatre. Unlike Western styles that heavily focus on the actor’s physical expression, Sabitri-Kanhailal incorporated the concept of “breath” as an unseen but crucial element. They believed the actor’s body, breath, and mind were intricately linked, with changes in breath manifesting in physical movements and vice versa.This focus on the subtle control of breath distinguishes their approach from methods that emphasise the outward expression of the body alone. It sounds more like yoga, doesn’t it?

Furthermore, Sabitri-Kanhailal theatre distanced itself from the “theatre of roots” movement, which often presented exotic spectacles based on specific cultural traditions. They didn’t rely on stereotypical portrayals of their Manipuri heritage. Instead, they drew inspiration from their culture in a more nuanced way, carefully incorporating elements of Manipuri society into their actions, gestures, and overall performances.

Such a balanced integration allowed them to assert their cultural identity without resorting to clichés or commodification. The core of their practice remained the harmonious coordination of movement with breath, creating a powerful and distinctive theatrical experience.

On reading the book

On a personal note, reading this monograph allowed me to step into the world of Indian theatre, which, to be honest, I wasn’t quite familiar with. In some ways, it challenged my assumptions about theatre, especially in the context of the peripheries of India.

The final chapter feels like the perfect closing act. An extensive interview with Sabitri offers a masterclass in her craft. If theatre interests you even a little bit, pick up this book. Immerse yourself in the journey of this phenomenal Manipuri woman whose name should be far more celebrated nationwide than it is today. Maybe we can contribute to that.