Lekhraj Tulsiani was a prominent voice in Sindhi literature, well known for his short stories. Born in Sindh in 1919, Tulsiani’s early life was steeped in the rich cultural diversity of this region, then part of undivided India.

Tulsiani’s world was dramatically altered by the partition of India in 1947. Sindh became part of Pakistan, and like many Sindhis, Tulsiani was forced to leave his homeland and migrate to India. This experience of displacement undoubtedly shaped his writing, and themes of loss, identity, and resilience can be seen in them.

If you’re interested in delving deeper into the world of Sindhi literature, you can read this post. And if you would like to explore Tulsiani’s works, I suppose, his short story “Manjri” would be a great starting point. Let’s read it, then.

Manjri by Lekhraj Tulsiani

Note: If you want to listen to the audio version of this short story, please click here.

The atmosphere of a moffusil court-of-law is not expected to be attractive. That of the Mirpur Khas court is no exception. A commonplace building, with no beauty of construction, no high tower, no big round pillars, no imposing dome.

As you enter the courtyard, there is nothing but dust to greet you and an air of desolation hangs all around. But in the midst of that desolation, there is a simple spot where one could rest for a while. In front of the court-house there are half a dozen large trees; four neem and two tali. That is the best resting-place in Mirpur Khas court.

Look at the trunk of each tree, its branches, its twigs—they are not trees, they are monsters! And the wind of Mirpur Khas! When the branches of those trees wave in the wind, monsters appear to be dancing!

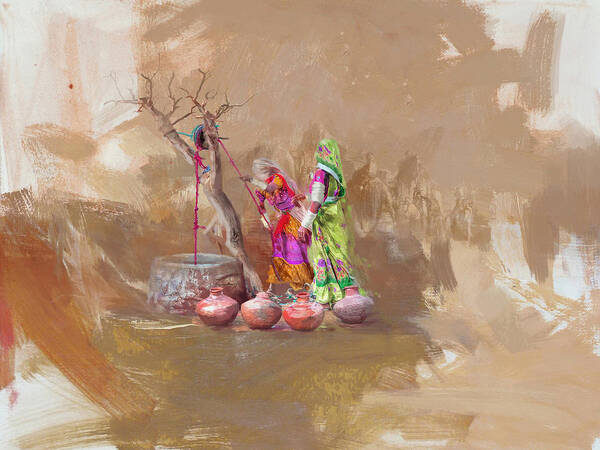

Under one of the neem trees, Manijri was seated. She was a low-caste Kolhi girl, but there was magic in her eyes, a magnet in her limbs! The eyes of every passer-by were attracted to her. But today clouds of sorrow had gathered on her round face. The lustre of her eyes had dimmed and her red lips appeared colourless. She wore a tattered skirt and her blouse could hardly conceal her brimming youth. Her chunni was waving in the wind. Her long hair, tied up with twine, fell dishevelled about her face, and as she pushed it back an alluring delicacy was revealed. What natural grace! No need for any artifice or blandishment!

Opposite Manjri, about a hundred steps away, under a tali tree sat a young man, handcuffed, a policeman standing by with a musket on his shoulder. The youth did not appear to be over twenty-four years of age. He had a brown, sunburnt face, strong arms, broad chest. He wore a dirty shirt and a coarse printed loincloth.

Manjri was glancing at him every now and then and lowering her eyes again. At times a long sigh escaped her. All her world was centred on that young man. Was he not enduring these difficult days on her account?

The young man, too, was looking at Manjri at frequent intervals, but there was no trace of suffering on his face. His looks were giving a message to Manjri: ‘‘Don’t lose heart, dear; even the scaffold would be my wedding couch, Manjri!”

At the call of the court, the policeman took the youth inside the building. After some time the naik loudly called thrice: “Is Musamat Manjri present?’’

Manjri, who was absorbed in her thoughts, was startled. She arose, collected her wits, and moved towards the courtroom. There was a strange fascination in her gait. The naik stared at her and twirled his moustache.

She entered the courtroom like a nervous deer, and all eyes as they were drawn to her grew wonder-struck. A voice said whispering, “What an attractive woman! Who would say she is a mere Kolhi girl? Look, how the woman walks—like a proud pea-hen!”

Manjri hesitated before the witness-box. The magistrate pompously ordered: “Get into the box, woman. What are you looking at?”

Manjri did not hesitate any more. She had come resolved to save Isro. Although she had no idea of the intricacies of law and the cross-examination of advocates, her firm resolve acted as a solace. She entered the witness-box and the court clerk administered to her the oath that she would speak the truth, nothing but the truth.

While making her statement Manjri faltered a little at first but soon got herself under control.

She began: “My parents were in debt to Mangal. In lieu of that debt, I was married to him. Mangal was an opium-eater and a debauchee. Every evening he used to take opium and come home in a semi-conscious condition. Every night he used to oppress me, and on my refusal to satisfy him he used to beat me up. He thrashed me more and more violently every day. After three months the house became hell for me. But I was newly married and bore everything with patience.”

“One midday I was carrying Mangal’s food to the field where he worked. Isro’s plot of land was near that of Mangal—just across the boundary. Isro was in his field, digging a water-course with his shovel. He had nothing on his body but his loincloth. He was exhausted digging with his shovel, and drops of sweat shone on his body. Broad chest, powerful shoulders and large sharp eyes. He was young and attractive. I stopped short. On the previous night, Mangal had beaten me severely and my limbs were aching. I called out to Isro and began chatting with him at random. He was not particularly interested in me. I induced him to come over to the shade of a tree. The water-course was running on one river and on its bank was a row of bushes. That’s how we knew each other, and our intimacy increased with each day. Isro never came to my house; I managed to meet him somehow or other. . .”

She faltered and added after a while, “In this case which Mangal has filed against Isro for seducing me, Isro is not to blame. He is faultless. It is all my fault and I am prepared for the punishment.”

One pleader remarked, “The whore has turned blind with love.”

Another said, “Can’t you give her credit for making her statement so boldly and frankly?”

The Magistrate smiled faintly and said to the advocates: “The time has come when women seducers should be punished instead of men seducers.”

The next day he delivered the following judgement:

“Although Musamat Manjri states—and there is a certain amount of sincerity in her statement—that it was she who seduced Isro and that Isro is not to blame, still from the legal viewpoint Isro is the culprit, because according to law man alone can be the seducer. Isro, the accused, has not defended himself and has confessed his illicit relations with Manjri—and on that account too he is the guilty one. But out of mercy, the court allots him the punishment of two months’ rigorous imprisonment only.”

Manjri’s eyes were involuntarily filled with tears. The lover for whom she had done so much, for whom she had shamelessly made such a statement in the open court—she had failed to save that devoted lover. She drew a long breath and looked at Isro. He was smiling faintly.

As the policemen were conducting him out, he passed by Manjri and whispered: “I am a man; the period of imprisonment will pass quickly, dear.”

In that single sentence, Isro poured out his whole heart to Manjri.

One pleader said to another: “Look, the slut is shedding tears for her illegitimate love.”

The other solemnly replied: “Friend, such love can’t be called illegitimate. This poor girl’s tears are also priceless, arising from the depth of her soul.”

The policemen took Isro away. With bowed head and faltering steps Manjri walked out of the court like a defeated soldier.

THE END

Translated from Sindhi by MU Malkani