Sant Singh Sekhon was a Punjabi writer who lived through a period of immense upheaval in India. Born in 1908, Sekhon witnessed the British Raj firsthand, the rise of Indian nationalism, and the traumatic partition of the country in 1947. This historical context is crucial to understanding Sekhon’s work, which often grapples with the social and personal costs of a nation in flux.

One of his popular short stories is The Whirlwind. It was translated into English by the author himself. When you look at the title, it seems ripe with possibility. Literally, it may seem like an actual storm, but as soon as you read a few lines, you get the idea that the author is talking about the storm of people.

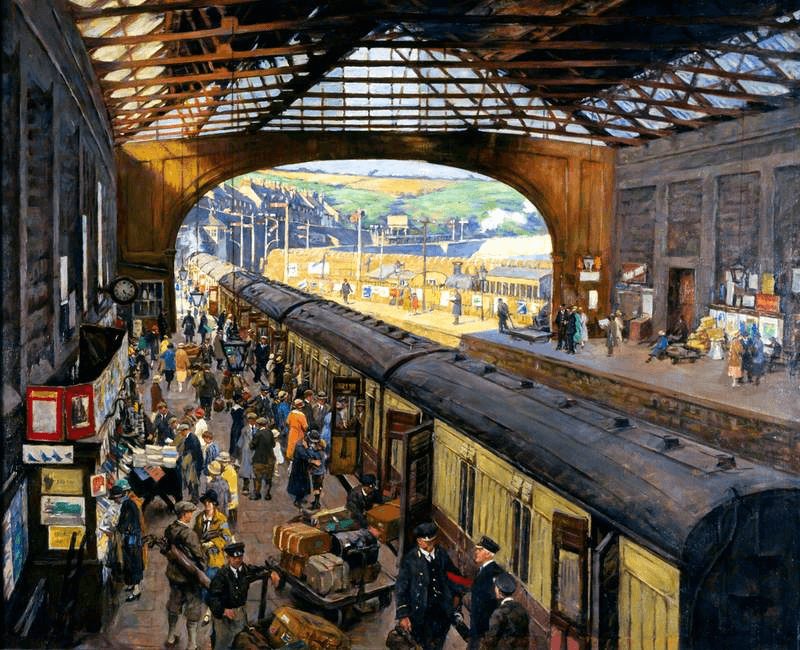

In this story, we step into a bygone era as Sekhon, the master storyteller, takes us to the 1940s Punjab. Unlike boring history books, Sekhon’s tale unfolds within the dusty confines of a small-town train station. Here, amidst the hustle and bustle of daily life, we get a glimpse of India as it used to be (or, still is, to some extent). Passengers from diverse backgrounds–a microcosm of the nation itself–weave through the public space, their stories telling the grander historical narratives of a nation on the cusp of change.

Note: If you would like to listen to the story in audio format, you can click here.

For our brave readers, here is the full text.

The Whirlwind (Translated from Punjabi by the author)

Platform No. 1 of Amritsar railway station was crowded with passengers. The up train to Lahore, scheduled to arrive at 13.00 hours, was late by over an hour and it would be yet another half-hour before it came.

Two young teachers of a local college, bound for Lahore, were walking up and down the platform, waiting for the train. Among the expectant passengers there were a few young women, sitting in more or less seclusion on benches or on their own suitcases, or just standing apart, and the two teachers were casting an occasional furtive glance at them. Women also, in a train or in a foreign place, are less restrained than usual in their manners. Young people make a public bestowal of affection in such situations, anxious to avail of the anonymity that a train journey offers. So there was nothing wrong with these two men or even with the women on the platform.

After they had been walking up and down the platform for some minutes, their eyes came to rest upon a young woman of about twenty-five or possibly younger. She was somewhat short-statured, a bit plump, but with a prepossessing face. Two policemen stood near her, evidently her escort.

“This woman cannot be the central figure in an elopement or abduction case,” said one teachers to the other. “She does not have that kind of a simple, roguish look. She has dignity about her.”

“She may possibly be a police officer’s wife,” the other added, “and these policemen may be on attendance till she is safely lodged in the train. But then, she is not that kind of proud in her bearing and she is not behaving stiff with the policemen. No, she is not a police sub-inspector’s wife, she is too plainly dressed, too, for that.”

The first was in agreement with these remarks and they cut a few circles on the platform.

“This woman’s appearance and ways are not those of a villager. She is half-villager and half-townswoman,” the first said again.

“Will you marry her?” the other asked and smiled.

“Wouldn’t wait for a more auspicious occasion,” the first replied and both laughed lightly. These intellectuals, though young, were evidently the sort that keep imagining incidents that could bring about a pleasant change in the tenure of their lives, with which they are ill content.

“I can say her husband is a very lucky fellow,” the second said further. It was easy to guess that she was married and also a mother. The next moment they saw her two-year old son. The boy was a healthy and smart child and seemed to take after his mother.

“Such women are generally ill-mated,” the first replied, believing that he alone deserved to be her husband.

“The child is like his mother.”

“Naturally, he is his mother’s child.”

“Boy, we must find out more about her, shouldn’t take such an idealistic view of the woman. For all one can say, she may be the heroine of an elopement drama,” the first protested, growing cautious.

“No, she cannot be that. All the same, I wonder what these policemen have to do with her.”

They were relieved to see coming towards them a man whom they knew for a talkative insinuating person and who they guessed would find out about the woman.

“Moulvi Sahib, will you find out who this woman is and what is the matter with her?”

The Moulvi Sahib had not been less curious. He had already made this enquiry.

“She is a Congress-worker, Sir,” the Moulvi Sahib replied at once. “They have brought her from Gurdaspur and she is being taken to Lahore. She has to appear there in a case tomorrow.”

“What is her name?” one of the young men asked impatiently.

“Kunti, Sir.” The Moulvi Sahib was well posted with information.

“Kunti,” the second repeated after a moment’s thought, “Kunti is a revolutionary worker who was arrested the other day along with her husband and co-worker for being in possession of revolutionary literature. She must have been taken to Gurdaspur in connection with the same case.”

“Yes, Sir,” the Moulvi Sahib confirmed.

These two and the Moulvi Sahib were not the only people whose interest had been aroused by Kunti. Numerous others were charged with similar curiosity and had learnt from various tongues something or the other about the object of their interest. The fact of Kunti being a Congress worker had enhanced her beauty in her admirers’ eyes and whoever happened to come under this double impact was overwhelmed.

In the flick of an eye, as it were, a whirlwind overtook the platform. Kunti was the power at the centre of this whirlwind. At first only the policemen, our two young intellectuals and the Moulvi had formed the body of the whirlwind, and a few khaddi-clad ones had also been drawn in. But now people from all comers of the platform were rushing in; in a few minutes there had gathered round Kunti a crowd of twenty to twenty-five. In another five minutes these grew to forty or fifty among whom there were five or six women also.

Nobody out of this crowd had yet addressed Kunti. The people were making and answering queries among themselves and a few, more forward, were having a conversation with the policemen. Kunti stood quiet in the midst of the crowd.

Who could say what thoughts were passing through her mind. On her face high seriousness and beauty seemed to be competing for pride. During these few minutes, did it occur to her that this crowd was drawn to her because of her beauty? But beautiful women are by no means a rare sight on railway platforms. If there is a lovely one in a corner, two or more young men would surely be found loitering around, watching her through the corners of their eyes, and at moments, to try his luck in a frontal attack, one or the other of them would look straight in her face. In such a case there is generally no response from the other party who a good deal abashed, bends her eyes down to the floor. If, instead, there are two or more pretty women, they will tell each other through looks or half-smiles that their scent or colour is inebriating the passers-by. Sometimes such a person may be accompanied by her husband who, if he is devoid of humour, will begin to evince uneasiness and make her feel uneasy too. But if he has some humour in him he would laughingly point to the onlookers’ preoccupation with her and thereby make her take it easy.

But Kunti knew that even though she was handsome, the people who had assembled round her were not actuated by youthful mischief, and so she stood there unperturbed. She was a little shy, no doubt, but all the same she was looking at the crowd with a sober mien, as a sister looks at her brother or a daughter at her father.

After a while a khaddar-clad, middle-aged man entered into conversation with her and caused the strain to relax a little.

It would be idle to affirm that Kunti’s beauty was not providing any physical stress in the spectators. Even these two friends of ours had taken in every line and contour of her body.

“She is a little heavy at the waist”, one of them remarked quietly to his companion. “Otherwise she is flawless.”

“Boy, the waist-line is perfect only for a year or two,” the other replied, “and then under nature’s law it must grow heavy. And I regard it not as a flaw but as a point of beauty, unless of course it is definitely mis-shapen.”

Kunti had by now isolated the women from the rest of the crowd and was talking to them. What could have been the theme of their talk? Someone might have asked simply,

“‘Sister, where are you coming from?”

“From Gurdaspur,” Kunti would have replied.

“What is the case you are involved in?”

“Nothing other than social work among the peasants.”

“This tyrannical Government does not spare women even,” an old woman would put in.

“But, daughter, why do you involve yourself in these matters? These are men’s quarrels and should be left to them. Now look, if you are sent to prison what will become of your child?”

Perhaps Kunti would have smiled at this piece of advice. And then someone braver than the others may have supplied “This child, mother, will go with her to prison. Wasn’t the Lord Krishna bom in a prison-house? Nobody can be better than he.”

Kunti must have smiled at this too and remarked to herself that the story about the Lord Krishna’s being in a prison was indeed a good idea.

One of the young men happened at this point to turn round and notice on a bench at some distance a suburban couple who had obviously traversed at leisure the smooth contours of youth. They had two children with them. All four were eating from a tiffin-carrier. The woman stood up to join the crowd round Kunti when the man extended his arm to stop her, saying “O leave it, what’s the use?”

“I’ll be back in a moment.” Saying this the woman disengaged herself from her husband’s extended arm and came to join the cluster of women who were talking to Kunti.

The young man invited his companion’s attention to her and both smiled.

“The wives of these townsmen have great courage and even more curiousity,” the other remarked.

From other platforms also men and women were being drawn in. Platform No. 1 was altogether empty of people as if they had been swept off it with a broom. From platform No. 2 about half the occupants had joined. The tale had reached platform No. 3 and the younger people from there also were rushing towards Kunti.

“Let us see when the station-staff joins this gathering,” said one of the young men, smiling.

“Here there is a combination of two forces,” added the other philosophically. “Beauty and idealism; two loves, love of woman and love of country.”

“That is why I have always held…” the second had started when the attention of both was attracted by Kunti’s child, who, cutting across the crowd about his mother, ran off down the platform. One of the policemen rushed after him to bring him back to his mother.

“Smart child,” someone remarked from near the policeman.

“Just like his mother,” the policeman replied, smiling. Some zothers also smiled.

The policemen were by now fed up with the crowd. Perhaps Kunti also had had enough of it. The crowd was asked to dispense. The signal for the train was down, too.

Spectators who had come from platforms No. 2 and 3 started running back to their places. Those from platform No. 1 also turned away to make sure of their belongings. The disinterested townsman’s wife rejoined him on the bench in the comer. He and the children had not let anything interrupt their eating. Back with them, the woman also took a bite or two and the meal was finished.

The Moulvi Sahib had no need to move, for he had throughout kept his bundle under his arm. The young teachers were travelling light, without any luggage, but they just moved away a little.

“That is why I have always held that patriotic and revolutionary movements need women’s participation. There are then two attractions for a man, the ideal of freedom and the love of woman. In European countries revolutionary struggles have never failed, for that reason. Think for a moment, boy, what a lot of strength Lenin must have derived in his lifelong struggle from Krupskaya’s comradeship.”

The train sailed in and people thrust themselves in wherever they could find room.

THE END