1962 was a significant year in history. It was when the two most populous nations on Earth, China and India, found themselves locked in armed conflict.

The Sino-Indian War, though brief in its duration, cast a long and chilling shadow. Its impact continues to ripple across the geopolitical landscape of both nations, serving as a stark reminder of the consequences of unresolved tensions. Recent skirmishes highlight the enduring nature of this conflict.

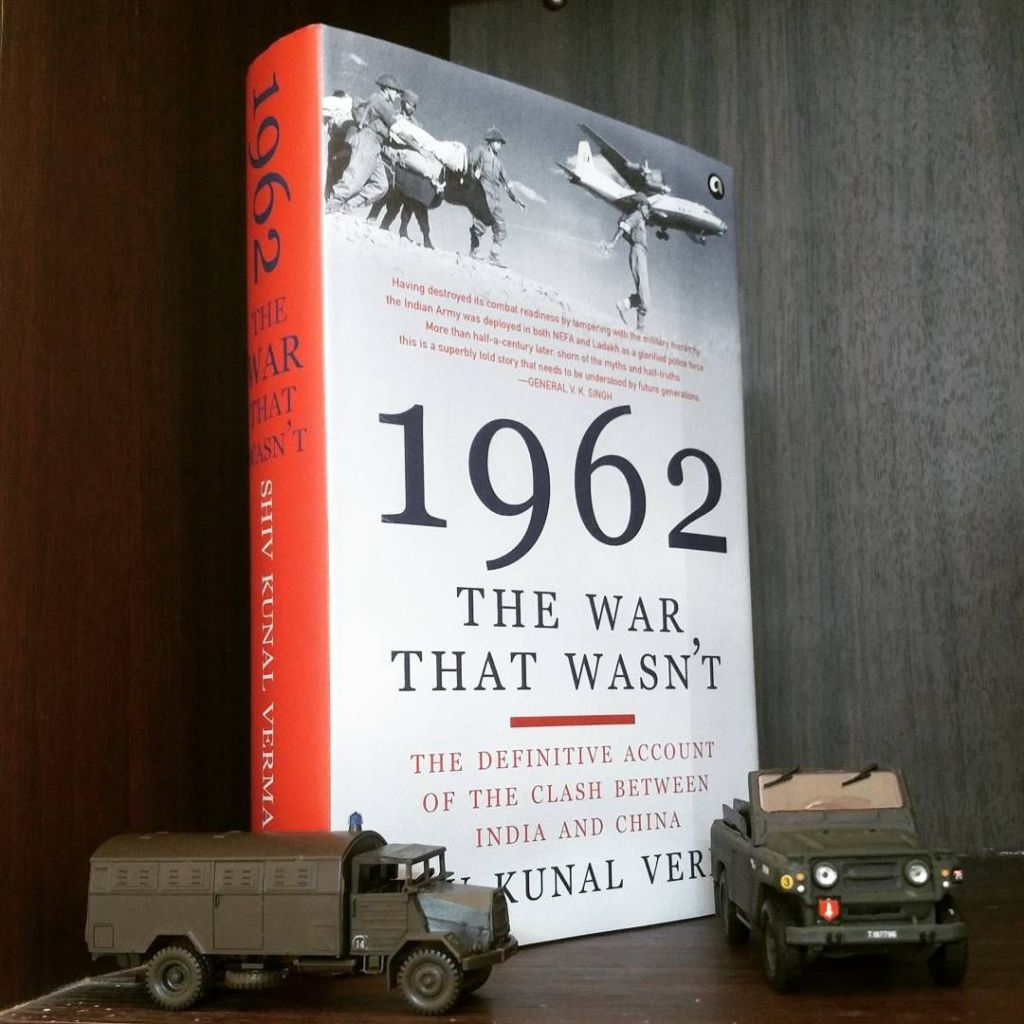

To fully understand the roots of this complex dispute, we must delve deeper, journeying back to the events preceding 1962, and perhaps even before that. And that’s why I have picked Shiv Kunal Verma’s book 1962: The War That Wasn’t. Let’s try to unpack the history with the help of this book.

Roots of the Dispute: Unclear borders and colonial legacies

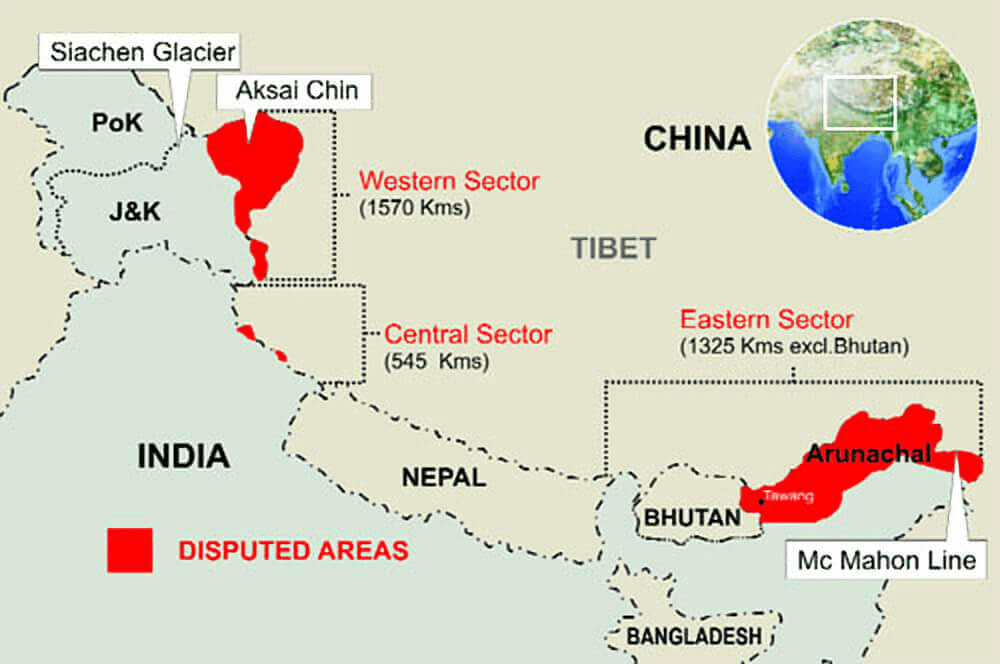

The core issue at the heart of the conflict lies in the differing interpretations of their shared border. This disagreement, like most others in the world, can be traced back to the days of British colonial rule. The British, seeking to secure India’s northern frontier, negotiated various agreements and drew lines on maps that became the source of endless debate. The McMahon Line, established in 1914, attempted to define the border between India and Tibet, but China never formally recognised it.

Adding further complexity has been the question of Aksai Chin, a desolate and strategically important plateau in the northwestern Himalayas. China claims it as part of Xinjiang province, while India maintains it belongs to Ladakh. India’s discovery of a Chinese-built road through Aksai Chin in the 1950s escalated tensions, bringing the latent territorial dispute to the forefront.

The India-China Politics: Ideological clashes and regional aspirations

The 1962 war wasn’t merely a matter of contested borders. Ideological clashes and perceptions of regional leadership also played a crucial role. India, recently independent in 1947, embraced a policy of nonalignment during the Cold War. Communist China, on the other hand, saw itself as the leader of a resurgent Asia, wary of India’s close ties with the West, especially after the increased US aid following the war.

It would be fair to say that the two countries approached each other in different ways. While the Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision of “Hindi-Cheeni bhai-bhai” (Indians and Chinese are brothers) aimed for peaceful coexistence, China had other plans. Its forceful annexation of Tibet in 1950 shattered this idealistic vision. India’s decision to grant asylum to the Dalai Lama further inflamed China’s anger, raising concerns about potential Indian support for Tibetan independence.

Nehruvian Blunder: The path to war

In the early 1950s, whispers emerged about China constructing a road through Aksai Chin, a desolate region in Ladakh claimed by both India and China. However, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru downplayed these reports, viewing them as minor incursions. This misplaced trust culminated in a rude awakening in 1957 when Chinese newspapers announced the road’s completion, causing significant embarrassment and alarm within the Indian leadership.

Faced with this assertive Chinese action, India adopted a “Forward Policy” in 1961. This policy aimed to establish a chain of outposts along the disputed border to strengthen its territorial claims. However, this reactive strategy proved inadequate for several reasons.

First, unlike India, China had meticulously planned and prepared for a potential military confrontation. They had invested in infrastructure development, acclimatised their troops to the harsh Himalayan terrain, and bolstered their military presence near the border. In stark contrast, India’s forward policy was poorly planned and lacked sufficient logistical support for its newly established outposts.

Secondly, India’s stance on the Sino-Indian border dispute proved to be a strategic misstep. Its earlier policy of appeasement towards China, including its muted response to the annexation of Tibet in 1950, emboldened Chinese assertiveness and territorial ambitions. This timid approach, coupled with the delayed and inadequate response to Chinese incursions, left India ill-prepared for the inevitable conflict.

As a result, when the war finally erupted in 1962, it was a one-sided affair that ended in a decisive Chinese victory. Indian forces, unprepared and ill-equipped for the harsh Himalayan terrain, suffered a humiliating defeat within a month.

The Legacy of the War

The 1962 Sino-Indian War cast a long shadow over relations between the two Asian giants. For India, it was a crushing blow that shattered its faith in peaceful coexistence with China. The defeat sparked a national awakening, leading to a significant overhaul of India’s military. This included a strong emphasis on developing mountain warfare expertise and modernising its defense infrastructure, as evidenced by the establishment of the Integrated Defence Staff in 1963 and the formation of the Mountain Strike Corps in 1999.

China, on the other hand, emerged from the conflict with a bolstered sense of national pride and military superiority. It solidified its control over the disputed Aksai Chin region, which continues to be a flashpoint for tensions even today. You might recall the 2020 Doklam standoff, or the recent border skirmishes in the Galwan Valley–it’s a reminder that the shadows of 1962 still loom over us.