“What is home?” I often ask myself, echoing the sentiment of philosopher Gaston Bachelard, who delved into the poetic essence of dwelling. It’s also the question Edward Hollis asks in his book How to Make a Home.

Is home a physical haven, a sanctuary from the tumultuous waves of existence? Or does it reside in the intangible realm of memories and emotions, weaving itself into the fabric of our being? Can we find home in the embrace of a loved one, the whispering winds of a familiar landscape, or the distant echoes of childhood dreams? Perhaps the essence of home eludes definition, evading our grasp like a fleeting dream.

Instinctively, though, we all recognise what a home is, don’t we?

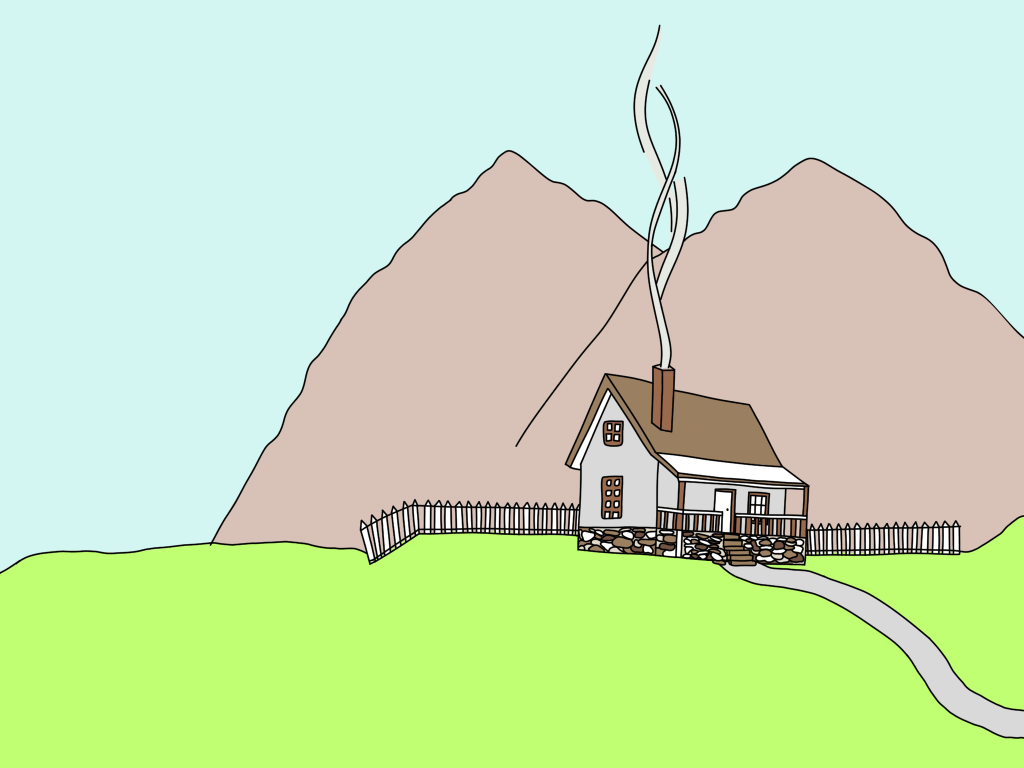

Ask a child to imagine a home, and they will always draw the same one. There will be a path leading from the garden gate to a front door flanked by square windows, the facade surmounted by a triangular pitched roof. Look on top, and there will be a chimney, complete with billowing smoke.

It’s an archetypal image — we all imagine the idea of home in this way. It’s a simple building, detached from the world by a garden, guarded by four stout walls, sheltered under a roof, and warmed by a fireplace. It’s a place of stability and order, guaranteed by the symmetrical placement of doors and windows. In Mandarin, the character for it, pronounced ‘shè’ is even drawn like one: 舍. It’s the sort of building we call a house.

But… does the home mean the same thing as a house? Certainly not. Things become slightly more complicated when we use the word home.

The architecture of our homes

Pull apart the child’s drawing, and you’ll find a similarly knotty etymology. The house is the building from which we begin, and it’s been around for so long, and has evolved over so many centuries, that it’s hard to imagine where it might itself have begun.

A house is made of walls and beams; a home is built with love and dreams.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

One might wonder: why do children, from this century or the previous ones, draw this archetypal image? Today’s kids might be living in a small apartment in one of those high-rise buildings, but they still think of the hearth and the garden as a key component of home. That’s because, deep down, we all have an understanding of home. We may not be able to articulate this emotion, but we feel it — every living being feels it.

Homing pigeons fly back to the place from which they came. Sports teams play at home or away. Languages play a special role in understanding this concept too. In Hindi, for instance, the word for house, grha, also means ‘family’. Home, in other words, is where we come from, and where we belong.

Home, to most of us, represents stability in an unstable world. Home is a metaphor for the self. Home is the storehouse of memory. Home is made by, and makes us, what we are. Home is where we can be ourselves. There’s nothing naive about that child’s drawing of a building. It’s a drawing of who you think you are.

And that’s the first thing we need to understand. Once we’ve wrapped our heads around this idea, we can move on to the fun stuff like decorating and keeping things tidy. All these points are discussed in great detail in the book — and you will have to read it for that.

A home without a house?

What if we don’t have all the things that constitute a home?

Well, in that case, the author suggests a simple exercise: a way to make a home when you’re not at home. Here is the exercise:

Go for walk — a walk you usually take.

It could be the walk to work, or the one you take on Saturday morning, to the shops. Take a map with you of where you’re going, and where you’ve been. Mark on it, as you go, the places you might stop at regularly along the way: the place you pick up a coffee, perhaps, or a newspaper. It could be as simple as the place you wait for a bus. Take a photo of each of these places, and when you get back to the place where you live, take a look at them: they are your home when you are away from home, or don’t seem to have one.

Why do you choose these places? Why one coffee stand over another? Why one side of the bus stop rather than another? What qualities appeal to you about these places?

Once you start pursuing these questions, you’ll start building a true home for yourself.