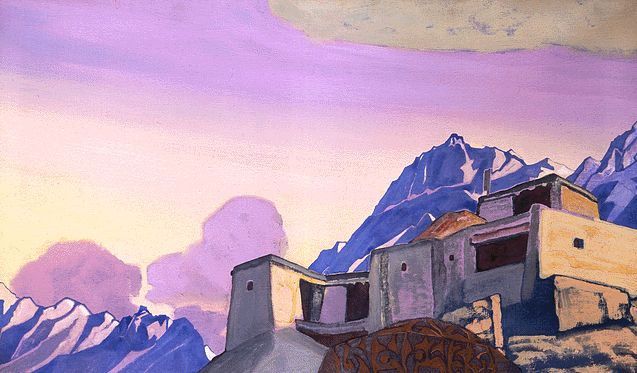

I live in Dharamshala, a small town nestled in the foothills of the mighty Himalayas. It’s a place where the hustle and bustle of the world seem to fade away, leaving behind only the whispers of the wind and the murmurs of the Tibetan community that call this place home.

It’s no wonder that tales of Tibetan life and lore fill the air like the aroma of momos cooking in the streets. From their epic journey into India to their colourful cultural traditions, not to mention their ongoing tussle with the powers that be in China, there’s never a dull moment in Dharamshala.

So when I stumbled upon Tsewang Yishey Pemba’s White Crane, Lend Me Your Wings, it felt less like discovering a new book and more like reuniting with an old friend. It was as if I was wandering through the familiar valleys and peaks of Tibet itself.

How the story unfolds

Pemba, a luminary in Tibetan-English literature, paints a canvas where East and West converge in some unexpected ways. The story begins with Pastor John Stevens and his wife, venturing from San Francisco to Eastern Tibet. It was their missionary zeal that had brought them here — the light of Christian faith had to shine in every corner of the world. That’s how they find themselves in the Nyarong Valley, a place they considered quite wild.

The couple begins their life in the Nyarong, Tibet, in an unexpectedly quiet, unexciting fashion. Nobody takes notice of their arrival nor displays any interest or curiosity. But, after they have built a small church and started their proselytising work, the interactions with the local community grow more frequent. The stage is set for cultures to collide or blend, yet somehow we manage to find a delicate balance between the two.

The interaction between Dragotsang, the local chief, and Pastor Stevens explains how they tread their differences.

“What is your work?” asks Dragotsang.

“It is to spread the message of our God. He is Yishu… the Son of God. He is the One True God. There is no Other God!”

“Ah, then He is Alllah! I have met many Tibetan Muslims and they all tell me that there is only One True God.”

“No… no… Allah is the Moslem God. We are Christians. Ours is the only One and True Religion.”

“We are Tibetans, followers of our own Tibetan religion; the altar of worship is infinite in extent. And there is always space for another deity.”

The cultural gaps seem significant when it comes to the more worldly matters. The pastor learnt that the Tibetan monks believed the earth to be as flat as a pancake, resting on the back of a giant tortoise (when the tortoise stirred, earthquakes occurred). They were also convinced that the sun moved around the earth, a belief so glaringly obvious, even the naked eye couldn’t miss it. Then there were disagreements regarding the exact location of the heavens. Both sides carried their unique ignorances in a blissful way.

With the arrival of little John Paul Stevens, the Stevens family gains a fresh face in their midst. The child grows up in Nyarong, soaking in the flavours of both cultures. He strikes up a friendship with Tenga Dragotsang, who teaches him a great many things.

It’s at this point in the book that we begin to see the darker aspects of Tibetan life. The brutality of tribal existence tightens its grip on young Tenga, leading him down a disturbing path towards planning a rape. John Paul, however, refuses to endorse the plan, sparking a rift in their friendship. In a twisted display of loyalty and bravery, John Paul sacrifices a finger to prove his allegiance. Now the stakes rise as Tenga is compelled to follow suit to dispel accusations of cowardice. Soon, the group finds themselves in a bizarre ritual of self-mutilation, each losing a digit in a chilling display of solidarity gone awry.

Maybe it was a sign of the more terrifying things to come!

The War in Tibet

The Sino-Japanese War had begun in 1937 and in 1941 the United States of America was also at war with Japan. Soon, the Japanese had conquered large areas of South-East Asia, and, with the capture of Burma, China was completely cut off from the rest of the world. On one side, the Japanese imperialism was expanding, and on the other, Mao Tse-tung and his Communist Red Army had their own plans. The war goes on for the next few years.

In 1945 the Sino-Japanese War ended with victory to the Kuomintang Chinese. But the real war that was to decide the fate of China began in 1946, the war between the Communist Kongtengs and the Kuomintang. The vast Chinese Nationalist Army was no match for the veterans of the People’s Liberation Army. The Kongteng Communists claimed that they had wiped out eight million KMT troops. In January 1949 the Red Army took Peking; in April, Nanking; and in May, they were in Shanghai. Now they were about to capture the Nyarong Valley. The Khampas of Nyarong had no other option but to fight the Chinese soldiers.

What happens next? The fate of Tibet may be written in the annals of history, but the destinies of these individuals remain a captivating mystery waiting to be unravelled within the pages of this book. You will have to read it to find out the answer.

Reading ‘White Crane, Lend Me Your Wings’ felt like holding a candle in a room shrouded in darkness, reminding me of the resilience of the Tibetan spirit. It’s a poignant reminder of the beauty and the struggles of a people whose wings have been clipped but whose spirit soars ever higher.