In 1947, the end of British rule led to the creation of India and Pakistan. While India aimed for a secular republic, Pakistan was established with a focus on religious nationalism. The nation was divided into East and West Pakistan, with power struggles between Punjabis in the West and Bengalis in the East, exacerbated by language issues.

The state’s preference for Urdu, favoured by the Punjabi and Urdu-speaking communities, led to tensions as the majority Bengalis resisted. Throughout the 1960s, Bengali grievances grew, fuelled by unequal resource distribution, economic exploitation, speech restrictions, and lack of political representation. Increasingly, the Pakistan Army and politicians began to view the Bengalis as rebels and anti-Pakistan. Political disagreements escalated into military intervention in East Pakistan by President Yahya Khan. And then there was Indian intervention on the other side.

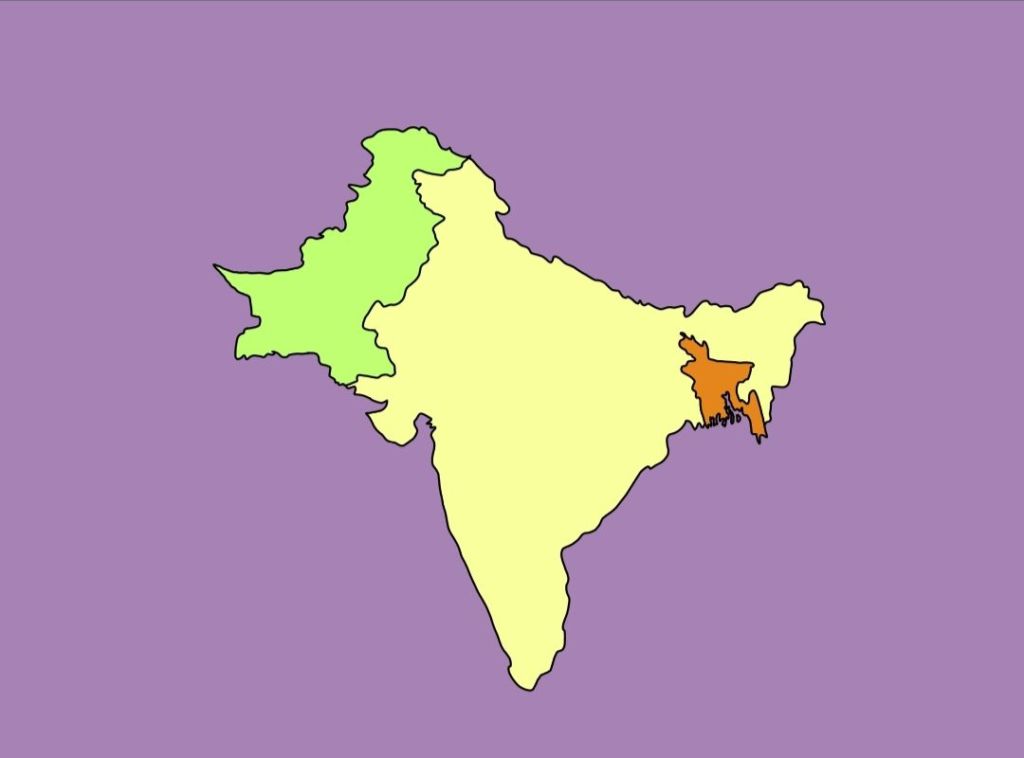

Eventually, in 1971, several wars broke out in East Pakistan (soon to become Bangladesh). One was a civil war between East and West Pakistan, the second was an international war between India and Pakistan, and the third was an ethnic war between the Bengalis and Biharis. There was still another war that broke out — a gender war of men against women in which all groups indulged in terrifying and brutalising enemy women to create fear and humiliate the other. It is this war and its horrifying accounts that Yasmin Saikia discusses in her book Women, War and the Making of Bangladesh.

1971 Victims’ Stories

Yasmin Saikia shares the narratives of women who suffered gender violence amidst the tumult of the 1971 war. These stories can be disturbing, and therefore, I kindly urge you to read only when you are in a healthy mental space.

Nur Begum’s Story

Nur Begum, a resident of Dinajpur, recounts the harrowing events she faced during the 1971 war. Married and residing in Chirirbondor near the border, her husband, his brother, and father fled to India when the conflict erupted. Left behind, Nur was pregnant with their daughter Beauty (pseudonym).

Things get worse from here. Nur’s husband was caught by the Pakistanis after being betrayed by local collaborators known as rajakars. The details of the torture are horrendous. Despite that, he clung to life, reciting verses from the Holy Quran. Eventually, they shot him in front of Nur, leaving her traumatised for life.

Nur’s family suffered further losses. Her parents were killed, and their village was left desolate. She, along with other young women, was taken captive in a bunker, where they were subjected to unimaginable suffering.

Then, one day, the war ended. But that was not the end of the story.

Following her rescue, Nur spent several months in a rehabilitation centre in Dhanmondi, where prominent figures and foreigners visited, offering support and arranging for her treatment. However, the trauma was going to have its consequences. She was shifted to a mental hospital, considering her deteriorating mental health. It was in this hospital that she gave birth to her daughter Beauty.

Despite Nur’s efforts, Beauty faced rejection due to her mother’s birangona (publicly designated any woman raped in the war) status. Nur, now married for the second time to a non-Bengali man, tried to provide for Beauty but faced difficulties in securing her a stable life. In the end we find her expressing frustration with a system that does not recognise her sacrifices and laments the challenges faced by her family. In the midst of health issues, she questions whether the country that she suffered for will bring any good to individuals like herself.

Firdousi Priyabhasani’s Story

In a turbulent environment marked by economic hardship, Firdousi Priyabhasani observed the stark reality of exploitation from an early age.

Struggling to make ends meet, she worked at a school earning a meagre salary. Despite her dedication to teaching, hunger and financial worries affected her performance. The affluent students mocked her, adding to her challenges. Firdousi faced hardships at home too, due to her family’s financial dependence and her mother-in-law’s cruel treatment.

Forced to contribute more, Firdousi sought work at a jute mill, where she encountered various challenges, including unwarranted advances. Her husband’s jealousy and interference worsened her situation. After false accusations led to her dismissal, she endured a tumultuous marriage, eventually opting for divorce.

Post-divorce, Firdousi, seeking financial stability, attempted to reclaim her job. However, a horrible tragedy was lurking. She was assaulted and gangraped in a car. The details are chilling. She was assaulted multiple times as the car drove through the dark lanes of the city. Then, they pulled her by hair and dragged her out. These men were officers of the Pakistan Army, mostly captains. And they kept shouting at her, “You are a Hindu. You are a spy.”

Among them was an officer, Altaf Kareem, who played a supportive role in her life post the tragic events. This was around a couple of months before the independence of Bangladesh. At the time, she was twenty-two, and Altaf Kareem was thirty. They shared a deep love, and he expressed a willingness to shoulder the responsibility of her children. When he left me for the last time, he gave her a salute and said, “Maybe, I will be killed.” She never saw him again.

The persecution did not stop there. She was victim-shamed in the following years. The stigmatisation led to her exclusion from various ceremonies, deemed inauspicious. That’s where her deepest regret lies — post 1971 treatment of the victims. The enemy did what the enemy did, but the friends could have been better. Let’s try to build a better world for Firdousi and millions of other victims of gender violence.