Mirza Ghalib — perhaps you’re already familiar with the name.

Born in the late 18th century, lived most of his life in the 19th, yet Ghalib’s legacy continued to grow in the 20th (and into the 21st as well). The great Urdu poet lived during the tumultuous times of the late Mughal period, and wrote about love, loss and existential challenges that were prevalent in that era.

Ghalib’s relevance persists in contemporary India and Pakistan, transcending the boundaries of time and geography. His exploration of universal themes, especially involving the complexities of human relationships resonates with readers today. On the one hand, his words provide aesthetic pleasure, and so they mesmerise you right away — and yet, his wisdom goes much deeper, fostering a better understanding of the intricacies of life across generations. Ghalib’s ability to articulate the nuances of emotion and the human experience is remarkable.

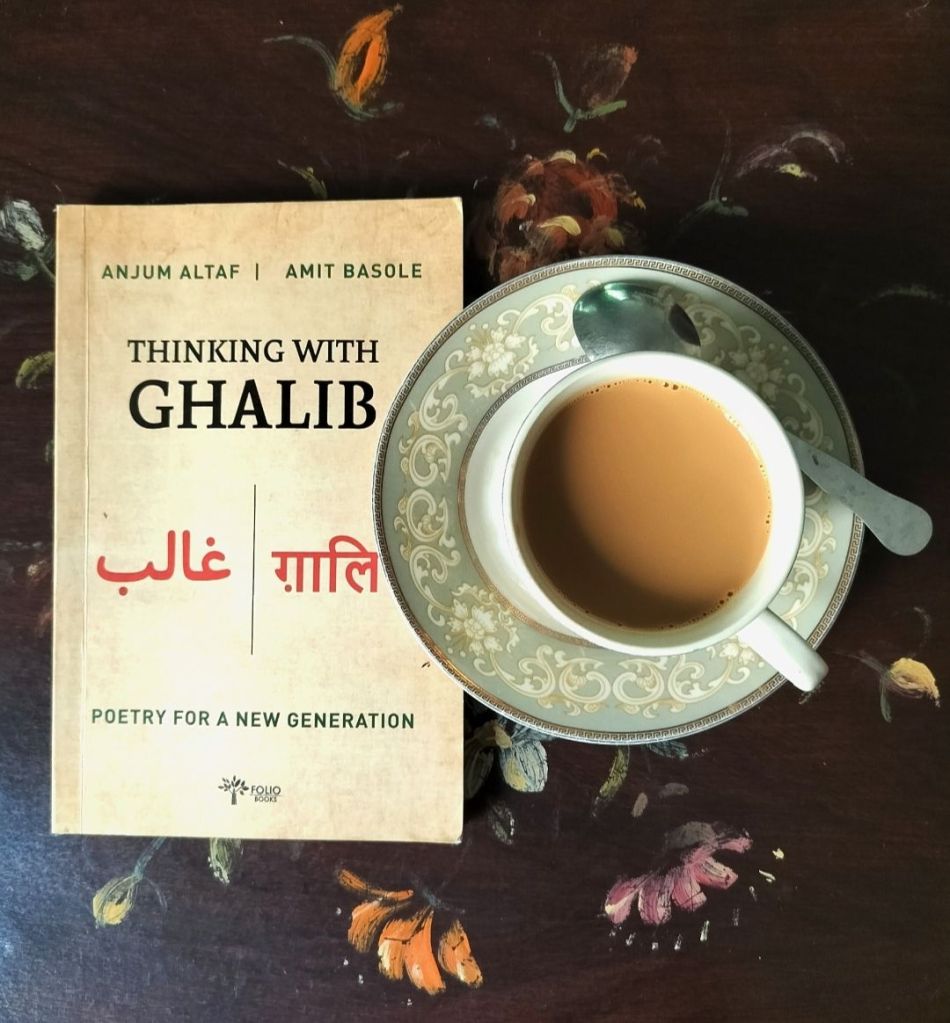

Recently I picked a book called Thinking with Ghalib. And… surprise, surprise, it does exactly what the title suggests! It allows you to think with Ghalib. The authors, Anjum Altaf and Amit Basole, suggest that the most fundamental and profound questions that Ghalib raised in his works, they remain relevant even today.

So, with that in mind, let’s explore what Ghalib has to offer in the times that you and I live in.

Ghalib on Relationships

Most of the people who read Ghalib would tell you that he is very, very romantic in his poetry. That’s certainly true. What we can also say is that he offers a valuable insight on the complexities of relationships as well. Take the following couplet, for instance.

Laag ho to usko hum samjhein lagaao,

Jab na ho kuch bhi to dhoka khayein kya?

Translation: If enmity would exists, then we would consider it affection.

When there is nothing how do we deceive ourselves?

It reminds me of the old saying: the opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference. Ghalib dramatises this message by giving an extreme example; even the beloved’s enmity is preferable to the absence of any relationship. Because the enmity at least allows the lover the illusion that it is a put-on, that in reality the beloved cares for the lover. Take away the enmity and we cannot deceive ourselves and are left without any hope of reconciliation.

The other way to interpret this verse, especially in today’s world, could be in the political context. You hear a lot of noise in politics, numerous protests, debates, heated exchanges, even violence — all that because people care. And it’s still better than a scenario when people would stop doing that.

Ghalib on Identity

One of the most famous verses of Ghalib explores the question of identity. It says:

Na tha kuch to khuda tha, kuch na hota to khuda hota,

Duboya mujh ko hone ne, na hota main to kya hota.

Translation: When there was nothing, then God existed; if nothing existed, then God would still exist.

‘Being’ drowned me; if I did not exist, then what would I be?

Now it gets tricky. There are a variety of ways in which the above verse can be interpreted. The question (what would I be?) is far from rhetorical. Ghalib leaves you with a serious contemplation about what would happen if you did not exist in the first place? Isn’t ‘being’ the very reason behind all your problems and suffering? How should you look at it? Take your time and reflect on it.

Ghalib on Justice

Ghalib encourages us to do the right thing and not give up on principles. Here’s a verse that can be directly applied in the political sphere:

Hum ne mana ki taghaful na karoge lekin,

Khaak ho kaenge hum tum ko khabar hone tak.

Translation: We accept that you will not show negligence,

But we will become dust by the time the news reaches you.

It reminds of what GK Chesterton said in one of his essays: that it’s better to cry before a calamity than after it. Of course, you can interpret it as a lover’s plea for the beloved, but you can also interpret it as anyone out there pleading to be rescued. It’s a clear reminder that the help must reach on time. Otherwise there is no point in it when all the war is over.

Is that it?

Certainly not. I have just mentioned three points here, but you’ll find dozens more when you pick up the above book, or read any of Ghalib’s works. In his poetry, you’ll encounter not just verses but windows to the soul, where the beauty of language and the depth of human experience intertwine, making you think beyond your everyday life — which is really the intention here.

PS: I recently wrote a newsletter on Ghalib. You can check it out here.