Since the beginning of civilisation, humans have tried to hold water for their consumption. In India, techniques to store and source water have evolved from the Great Bath of Mohenjodaro to modern dams and reservoirs.

In the last 1500 years, people in South Asia have refined their ways of accessing subterranean water by extending the utility of wells. We started by digging wells, building step ponds and baths, and later realised that water used for bathing and drinking was no longer potable.

Hence, the architects came up with an interesting solution in some parts of the subcontinent, where wells and tanks were constructed separately yet connected by a window. These structures became popular by many names like bawadi, bavari, vaav, pushkarni, barav, baoli, bain, or simply ‘stepwell’ in English.

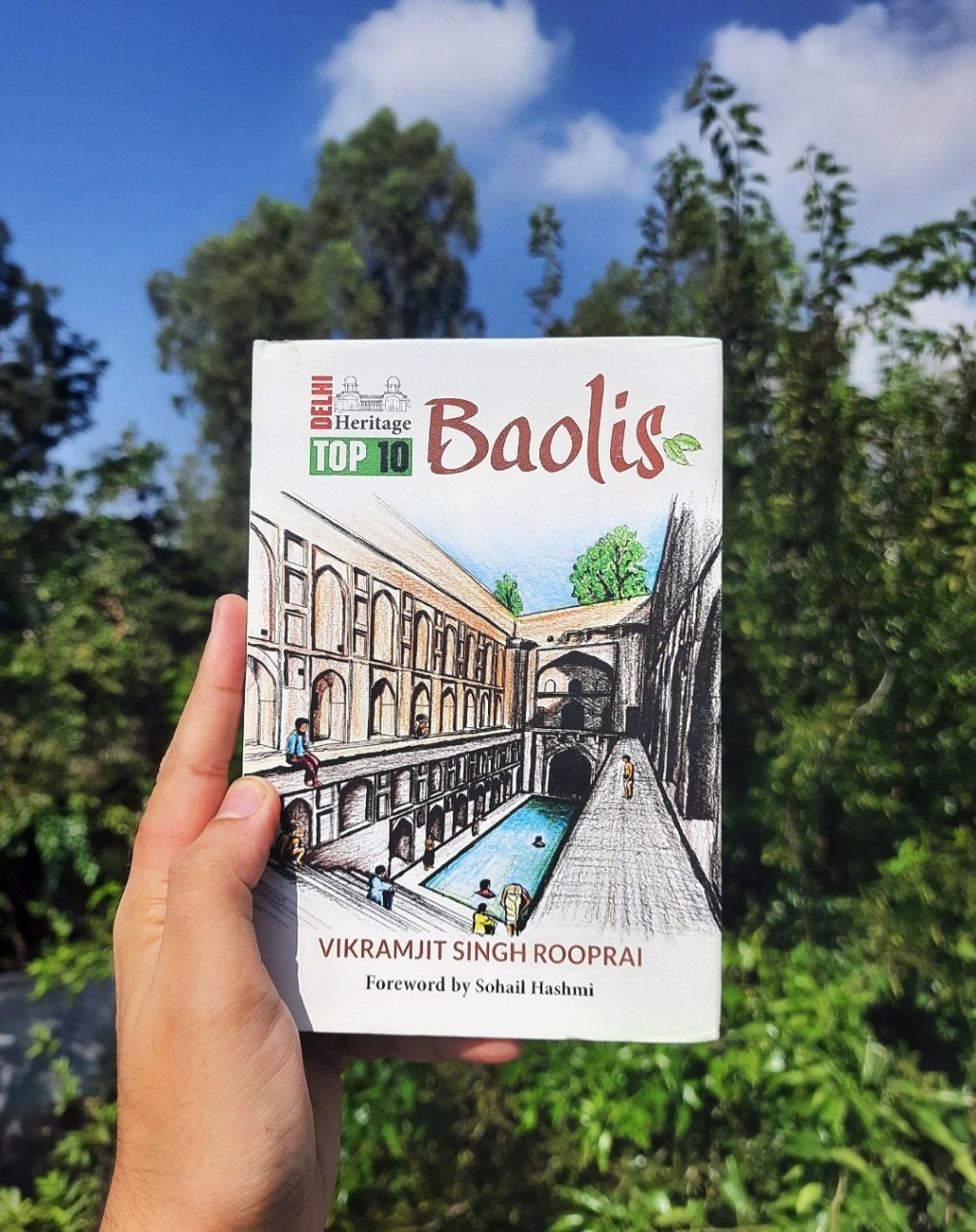

I grew up in the Himalayas, where the term bawadi (sometimes Bain) was commonly used. I remember, as kids, we would walk down the hill, step into one of these stepwells and fill our containers with water — much of which we would drink on the way back. There are so many memories associated with baolis, and therefore, when I picked the book called Delhi Heritage — Top 10 Baolis, I got excited. I didn’t know that Baolis exist even today that too in a city like Delhi. However, much to my surprise, there are quite a few, as listed below:

- Kotla Feroz Shah Baoli

- Red Fort Baoli

- Ridge Baoli

- Hazrat Nizam-ud-Din Baoli

- Ugrasen ki Baoli

- Munirka Baoli

- Gandhak ki Baoli

- Purana Qila Baoli

- Rajon ki Baoli

- Loharheri Baoli

Vikramjit Singh Rooprai, the author, has also given a special mention to two baolis: Baoli of Meherban Agha’s Mandi and Baoli of Dargah Khwaja Kaki. As Vikramjit tells us, there is a story associated with each one of these places. And while the structures themselves may not have survived the invasions of modernity, their memories still linger on.

Those of you who may not have seen them, a typical baoli in Delhi was historically constructed with meticulous planning and craft. It consists of a well which is attached to a separate water tank or basin. Wells are dug deep enough to penetrate the underground confining the impervious layer (crossing the underground water table/unconfined aquifer).

Tanks are built at a much lesser depth with a window between the well and the tank. They may or may not connect with the first layer of underground water aquifer. The window allows water to get transferred from the well to the tank. Since the tank has a larger surface area, it exerts less pressure on the water surface. On the other hand, the well is a long cylindrical shaft exerting high pressure on the water, thus transferring water from the well to the tank, but not vice versa. Medieval builders believed that since the water from the tank can never return to the well, the tank water can be used for bathing, washing, and other chores without the risk of it contaminating the water in the well, thus making the well water safe for drinking.

So the next time you are in Delhi, don’t forget to visit one of the baolis — and you might want to carry this book with you.