The year was 1834. The East India Company was working to change the education system of India, trying to make it ‘modern’. In that year Thomas Babington Macaulay became the president of the Committee of Public Instruction. Declaring that a ‘single shelf of a good European library is worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia,’ he produced the following year his notorious ‘Minute on Education’.

Macaulay’s recommendations went into immediate effect — something that still bothers a lot of Indians.

A thoroughly English educational system was to be introduced, which, in Macaulay’s own ineffable words, would create ‘a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinion, in morals and in intellect.” In 1836, he wrote that:

No Hindu who has received an English education ever remains attached to his religion. It is my firm belief [so they always were] that if our plans of education are followed up, there will not be a single idolater among the respectable classes in Bengal thirty years hence.

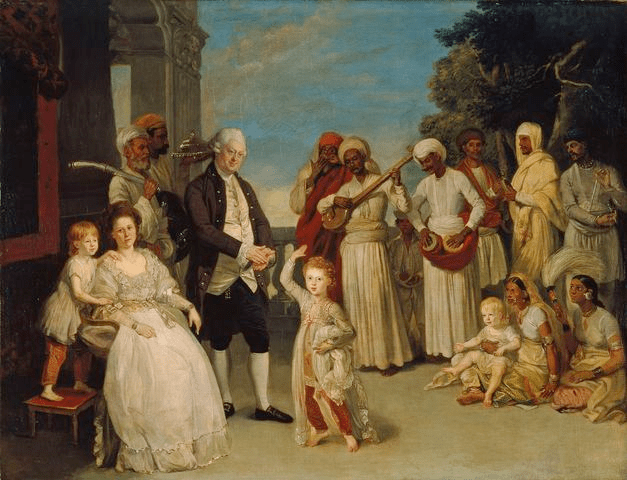

What is worth noticing is that there was a long-range policy, consciously formulated and pursued, to turn idolaters into people culturally English. A sort of mental miscegenation, which shows how, during the Victorian age, the British imperialism made enormous progress in daintiness. It can be safely said that from this point on, all over the expanding empire, Macaulayism was sincerely pursued.

The other side of it could be seen in how the Indian mind has perceived Macaulayism over the years. Even today, if you ask an Indian about Macaulay, you would find some bitterness in his/her remarks. It was no different in the colonial era either — if anything, it was worse. For instance, Bipin Chandra Pal, in 1932, wrote that Indian magistrates:

had not only passed a very rigid test on the same terms as British members of the service, but had spent the very best years of the formative period of their youth in England. Upon their return to their homeland, they practically loved in the same style as their brother Civilians, and almost religiously followed the social conventions and the ethical standards of the latter. The Indian-born Civilian practically cut himself off from his parent society, and lived and moved and had his being in the atmosphere so beloved of his British colleagues. In mind and manners he was as much as Englishman as any Englishman. It was no small sacrifice for him, because in this way he completely estranged himself from the society of his own people and became socially and morally a pariah among them.... He was as much a stranger in his own native land as the European residents in the country.

The reason behind the bitterness should be fairly obvious now. The British wanted to turn a native into an Englishman because they thought he was an inferior species who had no manners, wisdom, or taste. They felt the need to alter the morals of natives because the natives were not civilised in their minds. This view was highlighted multiple times by a number of prominent people in the colonial era. Consider the following examples.

In November 1891 Rudyard Kipling visited Australia, where a journalist asked him about the ‘possibility of self-government in India’. ‘Oh no!’ he answered: ‘They are 4,000 years old out there, much too old to learn that business.’

Where Kipling laid emphasis on the antiquity of the Indian civilisation, other colonialists stressed the immaturity of the Indian mind to reach the same conclusion, that Indians could not govern themselves. A cricketer and tea planter insisted that, “chaos would prevail in India if we were ever so foolish to leave the natives to run their own show. Ye gods! What a salad of confusion, of bungle, of mismanagement, and far worse, would be the instant result.”

Winston Churchill called the idea of independent India not only fantastic in itself but criminally mischievous in its effects. In fact he went a step further to claim that, “If Independence is granted to India, power will go to the hands of rascals, rogues, freebooters; all Indian leaders will be of low calibre and men of straw. They will have sweet tongues and silly hearts. They will fight amongst themselves for power and India will be lost in political squabbles. A day would come when even air and water would be taxed in India.”

And yet, here we are. A 42-year-old Indian-origin man is the new prime minister of Britain. A lot can be said about the changed attitudes, but Indians can do the job with a single sentence: finally, the son is set on the British Empire.