When you travel in India, you hear this word a lot, especially if you are a foreigner. But, what does Firangi mean? Let’s find out with the help of Jonathan Harris’s book The First Firangis: Remarkable Stories of Heroes, Healers, Charlatans, Courtesans, and other Foreigners who Became Indian.

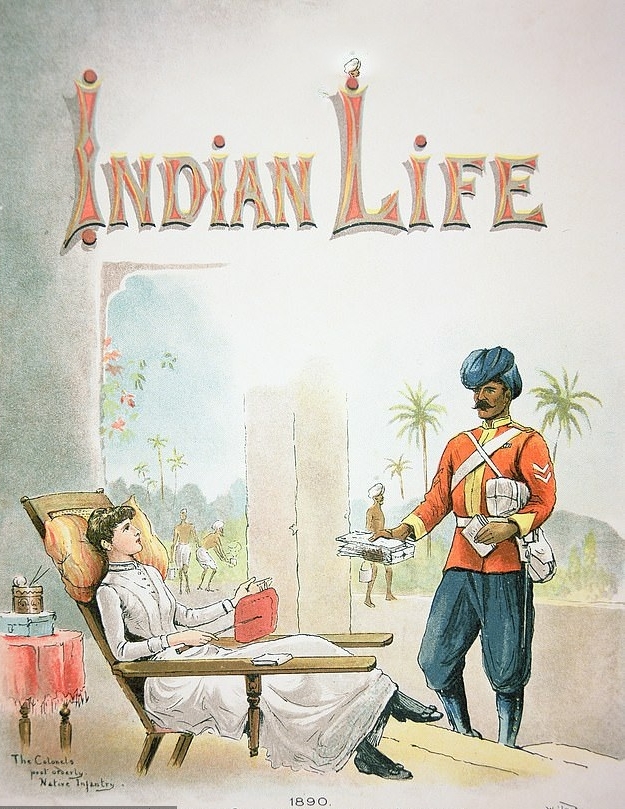

‘Firangi’ is a fascinating word. A variant term will be familiar to aficionados of Hobson-Jobson and British Raj literature, in which ‘feringhee’ is a common Indian term of abuse for white colonists. Another form will ring bells for fans of Star Trek, in which the ‘Ferengi’ are a race of unscrupulous intergalactic traders.

The term’s most common English translation, ‘foreigner’, doesn’t do justice to its subtle shades of meaning. Firangi is a broad synonym for the Hindi videshi (alien) and pardesi (outsider). But these two Hindi words are also a world away, from ‘firangi’, a Mughal-era Persian loan word from the Arabic farenji, meaning ‘Frank’ or Frenchman, but applied broadly to Christians. Franks, after all, dominated the ranks of the first waves of the Crusaders.

Origins of the term

Garcia da Orta insisted that the word ‘firangi’ refers exclusively to European Christians. This was on the basis that north African Coptic Christians were distinguished from farenji Christians living in Cairo. Yet the term’s multiple, shifting Indian usages from the sixteenth century to the present tell a much more complicated story.

First employed by the Mughals as a blanket term for any Christian, ‘firangi’ has been subsequently applied to white Europeans, brown Armenians, ‘black’ mixed-blood Portuguese Indians, Muslim Africans, and now foreigners resident in India. In sum, its referent is far from self-evident.

‘Firangi’ doesn’t so much describe a specific ethnic or religious identity as it troubles the very idea of identity itself. To the extent that it does point to any specific identity, it is an identity at odds with itself: a migrant to India who has become Indian, even as — or because — they continue to be marked as foreign.

From ‘feringhee’ to ‘ferengi’, and through all its other shifts in usage, firangi has retained its derogatory implications. In colonial India, it was a synonym for syphilis as well as for the British. How about that? Perversely, however, it has also been employed as an affectionate name for Indians, especially in rural circles.

One of the leaders of the Quit-India-Movement in Bengal was a Dalit from Darjeeling named Munshi Firangi. British Raj court records from the mid twentieth century list dakaits (bandits) from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh named Firangi Rai and Firangi Singh. Likewise, one of the gangsters in Omkara, a Bollywood adaptation of Othello, is named Kesu Firangi.

What does firangi mean today?

In its contemporary rural underworld usage, the name ‘Firangi’ possesses a hint of outlaw glamour. This may derive in part from a buried memory of those sixteenth-century military regiments in the Deccan sultanates known as the firangiyan, foreign soldiers who had gained a double-edged reputation as lethal experts in artillery and as low-life drunks. Perhaps a similar buried memory lurks also in the Urdu tradition of dastangoi. It was a form of story-telling popular in north India until the late nineteenth century.

From underworld criminal culture to popular story-telling tradition, then, the word ‘firangi’ connotes foreignness in potentially positive ways. Also, it paradoxically signals one’s place — liminal or criminal though it may be — within a specifically Indian community. And it does that in a way that pardesi or videshi does not.

In addition to Indian bandits named Firangi, we find several foreigners entering into service with an Indian master and being given the new name Firangi Khan. In other words, the proper noun ‘Firangi’ could name a local partisan as much as a foreign enemy.

The identity of a firangi

The term ‘Firangi’ is also tied closely to the question of identity. A firangi is an outsider but he is trying to assimilate. Many poor firangis of the past have passed as Indian. To do so, they needed to master local languages, wear local clothes, and learn local customs. They needed to be absorbed into local social structures: political, professional, religious, familial, etc. This, of course, bonded them closely to Indian masters, co-workers, friends, and lovers.

The first firangis were most authentically Indian when what they created in India was simultaneously local and foreign. That’s the beauty of it. Becoming Indian was — and still is — intimately connected to a process of Indian-Becoming. Which is to say: the ‘Indian’ is always becoming something new, and is constantly being renegotiated and transformed in a multitude of ways, because of unexpected conversations between local traditions and foreign elements.