Calcutta was a city certainly befitting royalty during its tenure as the capital of British India from 1772 to 1911. Law and order were excellent and the city was at the heart of a thriving economy. Migrants from other parts of the country and from foreign lands came to the city. Expatriate communities, including Armenians and Parsis from Iran, Jews from Syria and Baghdad, and the Chinese began making niches for themselves in Calcutta, which was, at that point of time, considered the second city of the British Empire.

Calcutta became a cosmopolitan melting pot, where cultures merged to provide a common platform on which great fortunes could be built. This cosmopolitan nature of the city brought about a diversity in food that had never been seen before. The white memsahibs who had begun to run households in British India taught their local staff the essentials of British cooking, and the intricacies of handling crockery and cutlery. The best cooks were deemed to be the Mogs, many of whom had migrated to the city from Chittagong or Hooghly. This brigade of chefs travelled every day to Sir Stuart Hogg Market, popularly known as New market, to buy the groceries and other ingredients they needed.

Sir Stuart Hogg Market has an interesting story of its own to tell. Legend has it that the “whites” resented brushing shoulders with the locals in the markets, and longed for a market, exclusively of their own. Finally, the Calcutta Corporation paid heed to their demand and purchased Lindsay Street, razed the old Fenwick’s Bazar located on it, and in its place erected Calcutta’s first municipal market. This market, built in the Victorian Gothic architectural style, was opened in January 1874 amidst much fanfare and the delighted Europeans gave it the provisional nickname, “New Market”.

Everything that could be possibly imagined was available for sale in this market, right from fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, groceries, spices, cheese and confectioneries to crockery and cutlery, utensils, clothes, shoes, flowers and books.

Prolonged exposure of the local Bengalis to a diverse world encouraged a progressive, tolerant and experimental outlook, which extended to their eating habits, creating a demand for different cuisines. Many local cooks became experts in European cuisine and their expertise gradually filtered through to the rest of the people who also developed a taste for these dishes. In addition, the culinary practices and food habits of the other communities living in the city, whether indigenous or expatriate, began to blend into the local culinary culture.

A number of eateries opened in Calcutta during this time, specialising in traditional as well as new-found cuisines, both of which were in great demand. Many of these eateries became the favourite haunts of freedom fighters, revolutionary leaders and thinkers, philosophers and litterateurs. Some of the patrons even made anti-colonial plans and wrote seditious literature in these places.

Calcutta’s Contemporary Culinary Culture

As Shashi Tharoor says in his book India Shastra, “one Bengali is a poet, two Bengalis is an argument, three Bengalis is a political party.” The joke actually reflects the life in Calcutta. The residents of this city, irrespective of their social strata, are so politically aware that heated discussions on art, literature, philosophy and politics in tea shops, coffee houses and office canteens have become synonymous with the very spirit of the city.

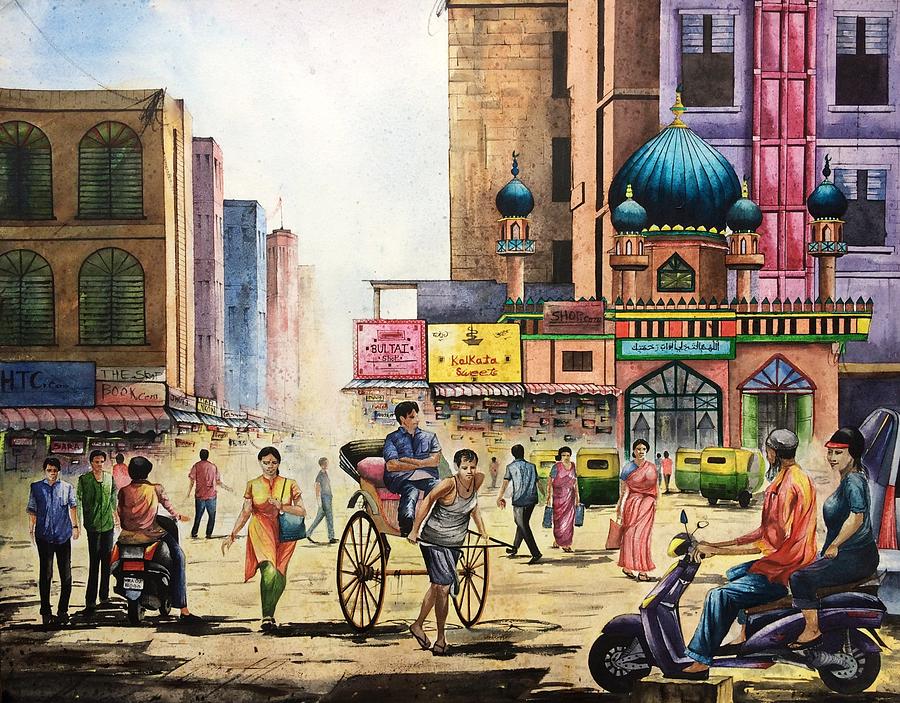

Food has always been an integral part of the lifestyle of the residents of Calcutta — and it still holds true. This become evident on taking a tour of the city, when one is sure to come across a multitude of endearing sights and sounds that represent “food”, whether it is the pani puri wallah, or rather, the phuchka wallah, selling his wares at the corner of a road, or the jhal muri wallah, selling the spicy puffed rice preparation, or the ghugni wallah, serving his customers the semi-dry and spicy preparation of whole yellow peas in bowls made of dried leaves. Scenes of pavement vendors selling cuts of fresh fruits sprinkled with sugar and salt, or hard-boiled eggs dusted with salt and pepper, or charcoal-toasted slices of bread smeared with butter and pepper, are common.

While, on the one hand, one can discover international fast food joints, Italian restaurants, Southeast Asian and East Asian restaurants, on the other, one may come across a multitude of restaurants specialising in the different varieties of Indian cuisine just as easily. At the end of a meal, a customer can buy the good old paan (betel leaf roll) from one of the numerous paan shops dotting the city.

Reference books: