China’s Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, would not have occurred if Mao Zedong had died before 1966. Mao planned it, launched it and had a greater hand in directing it than anyone else.

In Mao’s view, China’s Cultural Revolution lasted from 1966 to 1969, when the changes it had brought about were approved by a party congress (the ninth) and registered in a revised party constitution. In the modern view of the party, it lasted for a full ten years. The decade of political conflict and social disorder only ended when the Gang of Four, Mao’s most radical associates, were arrested. In the latter perspective, it was a protean movement, constantly changing in character. Even before 1969, it had a triple character. It was a super-revolution intended to create attitudes and modes of behaviour which Lenin would have tended to associate with Left-wing socialism. It was a counter-revolution, intended to break down and re-create many institutions established under the new democratic and socialist revolutions of the 1950s. It was also a revolution for the sake of revolution, a process which Mao saw as having its own redemptive value.

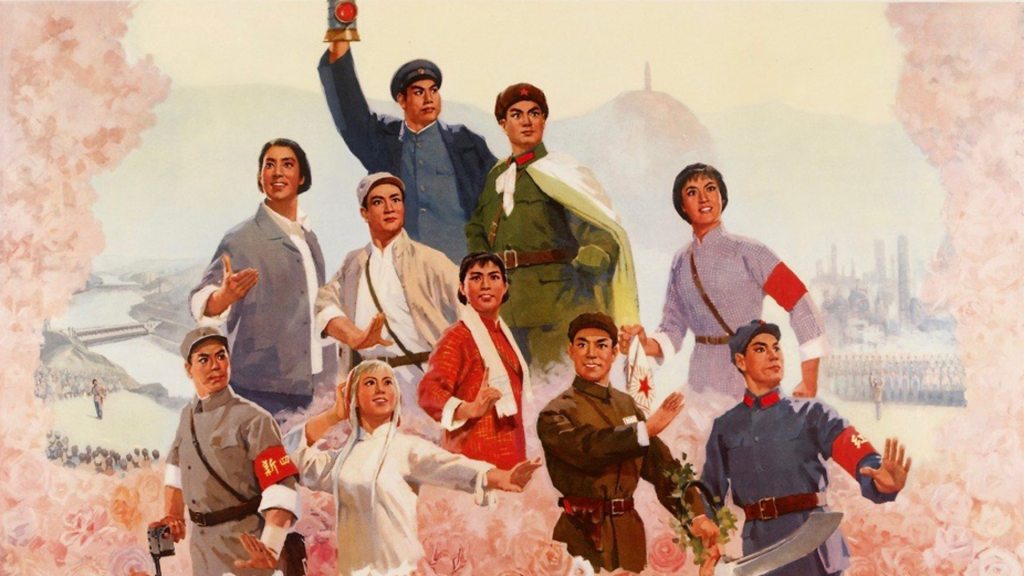

Among Mao’s purposes in launching the revolution, three are clear. One was to take much further the process of indoctrinating society in what he saw as socialist values, and creating structures to correspond with them, which had been under way since 1950. Among these values four stand out:

- equality

- community

- simplicity

- struggle

Struggle was a value for Mao because he believed that nothing worthwhile could be achieved without struggle, but also because he held — or came to hold — that socialism was not a steady state, which only needed protection once it had been achieved, but an unstable condition, in which regeneration was necessary if degeneration was not to set in.

Mao was an egalitarian and had no time for qualified forms of equality, such as equality of opportunity. In his picture of the good society, its members would resemble one another in outlook, level of education and standard of living. With this went his love of community. This had at least two sources: a conviction that a mass of people, properly stimulated and led, could achieve heroic results in any undertaking and a very strong distaste for individualism, which he tended to equate with selfishness.

Mao had a very deep grudge against the educated class of the old China, disliking their scholasticism and their contempt for the common people. Conversely, he admired the simplicity of the peasants. He associated their strength with freedom from corruption; and he wanted to preserve from corruption the peasant-soldiers who had fought and worked in the wilderness for small rations and very little pay when they ‘entered the cities’. In the mid-1960s, he also became concerned about the moral nature of the youth of China, who had not experienced war. He told several foreign visitors that he was particularly worried about the way in which the sons and daughters of old revolutionaries had become selfish and pampered.

In the light of all this, Mao favoured non-hierarchical institutional arrangements. In industry, he wanted the workers to play a part in management and to have an important say in decisions about targets and the use of technology. In agriculture, he wanted all activity to be organised on collective lines. In public health, he wanted a high proportion of the best-trained doctors to work in the countryside and a corps of less well-trained health workers — ‘barefoot doctors’ — to be stationed there permanently. In education generally, and especially in higher education, he wanted undemanding entrance examinations and courses with a large practical content. In literature and the arts, he wanted the clear projection of socialist values, in language and symbols which the less well educated would have no difficulty in understanding. More generally, he wanted to narrow the cultural and material gap between the cities and the countryside and to get rid of the distinction between mental and manual labour.

Mao’s second purpose was to recover the political power he felt was slipping away from his grasp. By the beginning of 1965, he had become angry about the extent to which the party’s central apparatus, under the control of Deng Xiaoping and supervised by Liu Shaoqi in the name of the politburo and its standing committee, had taken policy-making into its own hands. It was at about this time that he called Deng Xiaoping’s secretariat — or, according to Jiang Qing, his wife, Deng himself — an ‘independent kingdom’.

Mao’s third purpose was to train up ‘revolutionary successors’. He had become steadily more preoccupied about his own mortality as the 1960s went by — he became seventy in 1963 — and steadily more worried about what he saw as the lack of commitment to revolution in his colleagues. He was himself developing ideas which he ultimately put together in a general theory of ‘continued revolution under the dictatorship of the proletariat’, but he saw no enthusiasm for continued revolution around him.

Nevertheless, the time for a revolution had arrived.

PS: After achieving many of its goals, China’s Cultural Revolution finally came to an end when Mao died in 1976. Historians believe somewhere between 500,000 and two million people lost their lives as a result of it. In a bid to move on – and avoid discrediting Mao too much – party leaders ordered that the Chairman’s widow, Jiang Qing, and a group of accomplices (the Gang of Four) be publicly tried for masterminding the chaos.

Reference books: