In this post I am going to share the glimpses of Amrapali’s life through different phases. For that, I have used Ira Mukhoty’s book Heroines as a reference.

In the fourth century BCE, one of Alexander the Great’s admirals, Nearchus, described the clothes worn by the people of Vaishali (modern day Bihar, India) as cotton ‘of a brighter colour than found anywhere else’ which ‘the darkness of the Indian complexion makes so much brighter’. It is in this town we find Amrapali, a celebrated royal courtesan from ancient India. Also known as Amra or Ambapali, Amrapali’s name comes from a mango orchard where she was deserted as a baby.

Life of Amrapali as a Courtesan

Amrapali wears a diaphanous white and gold skirt and jewellery that shines with precious stones. From the courtyard behind her come the strains of musicians tuning their instruments for the evening’s entertainment. As dusk fills the sky, the wealthy men of the town, merchants and noblemen, enter the courtyard and seat themselves on the clean white diwans. This is the salon of the most famous courtesan of Vaishali, after all.

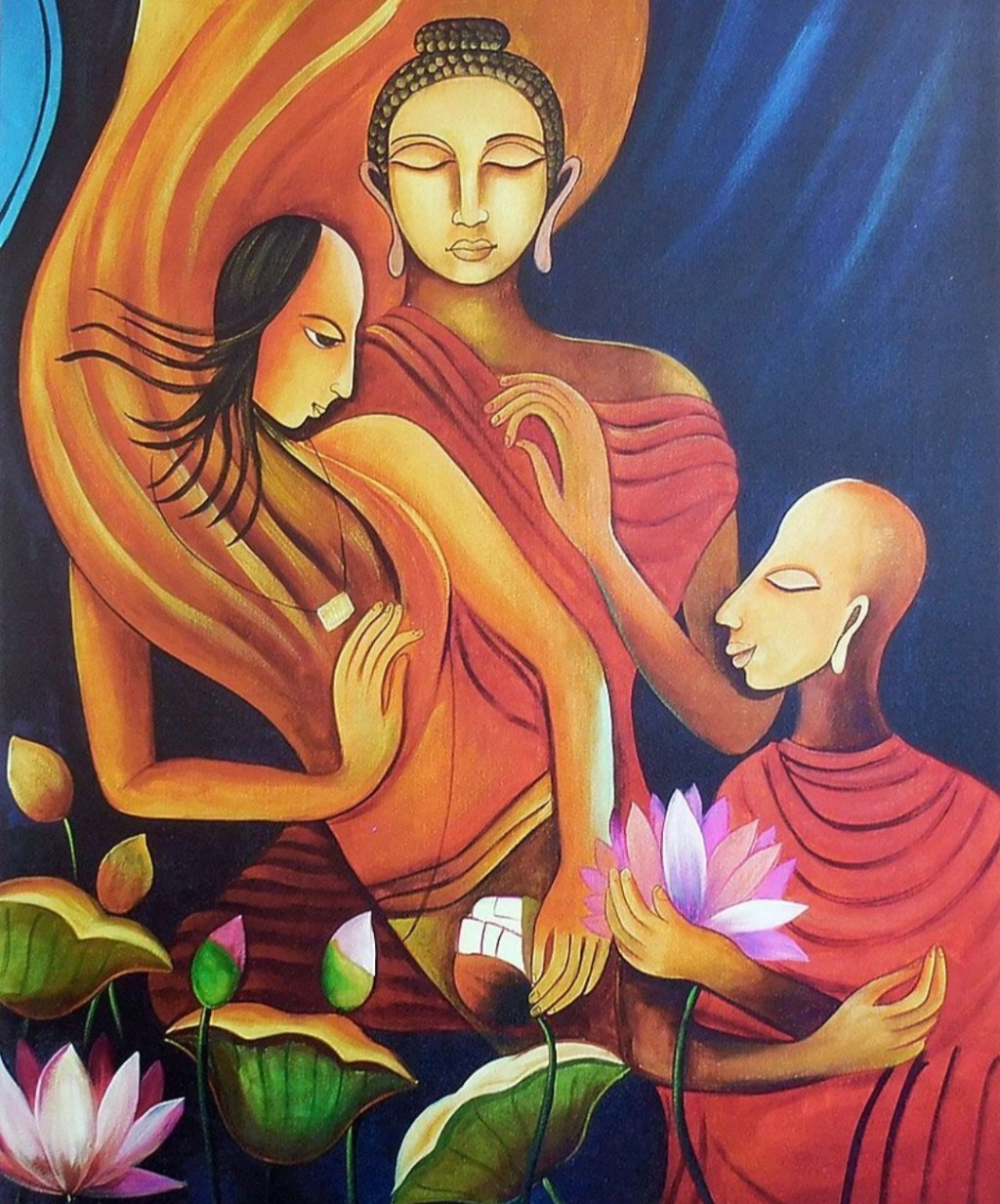

Amrapali has something else in her mind this evening. She is going to meet the Buddha the next day. She knows that he is a holy man and she is a courtesan. But, she has heard that the Buddha does not discriminate between anyone, rich or poor, man or woman. Amrapali does not know it yet, but this meeting is going to change her life.

“Do not go upon what has been acquired by repeated hearing; nor upon tradition; nor upon rumour; nor upon what is in a scripture,” the Buddha says when he meets her. “You yourself must know.”

Amrapali is mesmerised by this man who tells her to rely on her own instinct, who looks at her with compassion. She is not used to this. She is used to seeing only lust and desire in the eyes of men.

Life of Amrapali as a Buddhist Nun

In the next few years, she Amrapali will give away her considerable fortune — her talking parrots, ivory, handled vanity mirrors, carved wooden spice boxes and trunks full of silk.

She has spent a lifetime accumulating these objects, but now they don’t make a sense anymore. There is a deeper spiritual realisation. She is going to be ordained into the Bhikkuni Sangha. She will shave her long braid and exchange her fine linen clothes for the coarse ochre ones of the sisterhood.

As a Buddhist nun, the only possessions Amrapali would have been allowed were a set of clothes: undergarments, an outer garment, a cloak, a waist-cloth and a belt with a buckle. The only others allowed were practical ones, such as a begging bowl, a razor, a piece of gauze for filtering water to drink, a needle, a walking stick and a bag of medicines.

One of these is the Song of Amrapali

Black and glossy as a bee and curled was my hair: Now in old age it is just like hemp or bark-cloth. My hair clustered with flowers was like a box of sweet perfume: Now in old age it stinks like a rabbit's pelt. Once my eyebrows were lovely as though drawn by an artist: Now in old age they are overhung with wrinkles. Dark and long-lidded, my eyes were bright and flashing as jewels: Now in old age they are dulled and dim. My voice was as sweet as a cuckoo's, who flies in the woodland thicket: Now in old age it is broken and stammering. Once my hands were smooth and soft, and bright with jewels and gold: Now in old age they twist like roots. Once my body was lovely as polished gold: Now in old age it is covered all over with tiny wrinkles. Such was my body once. Now it is weary and tottering, The home of many ills, an hold house with flaking plaster. Not otherwise is the world of the truthful.

Once Amrapali entered the Buddhist Sangh, she disappeared into the anonymity of the sisterhood. Over the next few centuries, the Pali, Chinese and Tibetan canons would recount her story as an anecdote on the conquering of desire and the redemption of sinners, each version slightly altered depending on changing societal conditions.