Throughout history, one question has been thrown at women in one form or the other: can you do what a man can? Different societies in different times have asked this question differently. Can you cut trees like a man? Can you fight in wars like a man? Can you play like a man? Can you create art like a man? Thankfully, we live in much better times and these questions have become a rarity, and yet, we may have a long way to go.

The interesting point here is, why did people assume that women were incapable of greatness? Why did women not do things simultaneously as men were doing them? The answer to these questions are buried in the pages of history. And Virginia Woolf did try to uncover at least a few of them when she wrote her masterpiece A Room of One’s Own (1929). Below excerpts are taken from the book where Woolf talks about women in literature and outside it.

***

I went, therefore, to the shelf where the histories stand and took down one of the latest, Professor Trevelyan’s History of England. Once more I looked up Women, found ‘position of’ and turned to the pages indicated. ‘Wife beating’, I read, ‘was a recognised right of a man, and was practised without shame by high as well as low… Similarly,’ the historian goes on, ‘the daughter who refused to marry the gentleman of her parents’ choice was liable to be locked up, beaten and flung about the room, without any shock being inflicted on public opinion. Marriage was not an affair of personal affection, but of family avarice, particularly in the “chivalrous” upper classes… Betrothal often took place while one or both of the parties was in the cradle, and marriage when they were scarcely out of the nurses’ charge.’

That was about 1470, soon after Chaucer’s time. The next reference to the position of women is some two hundred years later, in the time of the Stuarts. ‘It was still the exception for women of the upper and middle class to choose their own husbands, and when the husband had been assigned, he was lord and master, so far at least as law and custom could make him. Yet even so,’ Professor Trevelyan concludes, ‘neither Shakespeare’s women nor those of authentic seventeenth-century memoirs, like the Verneys and the Hutchinsons, seem wanting in personality and character.’

Certainly, if we consider it, Cleopatra must have had a way with her; Lady Macbeth, one would suppose, had a will of her own; Rosalind, one might conclude, was an attractive girl. Professor Trevelyan is speaking no more than the truth when he remarks that Shakespeare’s women do not seem wanting in personality and character. Not being a historian, one might go even further and say that women have burnt like beacons in all the works of all the poets from the beginning of time — Clytemnestra, Antigone, Cleopatra, Lady Macbeth, Phedre, Cressida, Rosalind, Desdemona, the Duchess of Malfi, among the dramatists; then among the prose writers: Millamant, Clarissa, Becky Sharp, Anna Karenina, Emma Bovary, Madame de Guermantes — the names flock to mind, nor do they recall women ‘lacking in personality and character.’

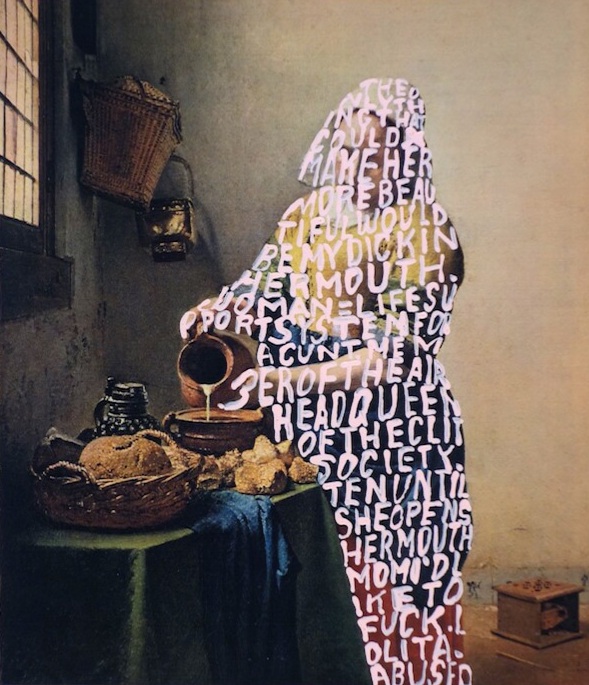

Indeed, if woman had no existence save in the fiction written by men, one would imagine her a person of the utmost importance; very various; heroic and mean; splendid and sordid; infinitely beautiful and hideous in the extreme; as great as a man, some think even greater. But this is woman in fiction. In fact, as Professor Trevelyan points out, she was locked up, beaten and flung about the room.

A very queer, composite being thus emerges. Imaginatively she is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant. She pervades poetry from cover to cover; she is all but absent from history. She dominates the lives of kings and conquerors in fiction; in fact she was the slave of any boy whose parents forced a ring upon her. Some of the most inspired words, some of the most profound thoughts in literature fall from her lips; in real life she could hardly read, could scarcely spell, and was the property of her husband.

***

Virginia Woolf acknowledges that creating great art or literature is a feat of prodigious difficulty. Everything around us is against it. Dogs will bark; people will interrupt; money must be made; health will break down. Both men and women face these mammoth challenges. However, she adds, these difficulties were infinitely more formidable for women. And then she says something that will be remembered for a long, long time: that, in the first place, a woman needs to have her own room.

Reference books: