INDIA is merely a geographical expression. It is no more a single country than the Equator.

Winston Churchill

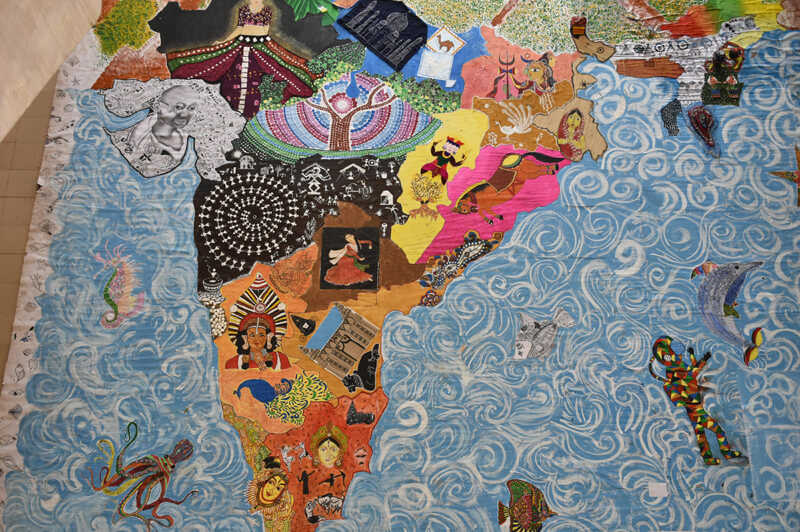

Churchill was not the first person — or the last — to make such observation about India. The diversity of India has baffled many throughout the history; it still does. However, the important question is, did the British somehow create India? Was there no such thing as a united India before the British colonised it? These questions are still being asked, particularly in India and Pakistan, and answered conveniently as per one’s political views.

Amartya Sen, Indian economist and philosopher, dealt with these questions in his 2005 book The Argumentative Indian. Let’s see what arguments did he put forward to solve this puzzle.

Ancient scriptures

Vishnu Purana being one of the oldest and most authentic puranas has a great description of Bharata (India). It says:

THE country that lies north of the ocean, and south of the snowy mountains, is called Bhārata, for there dwelt the descendants of Bharat. It is nine thousand leagues in extent, and is the land of works, in consequence of which men go to heaven, or obtain emancipation.

Vishnu Purana

The earliest recorded use of Bhārata in a geographical sense is in the Hathigumpha inscription of King Kharavela (first century BCE), where it applies only to a restrained area of northern India, namely the part of the Ganges west of Magadha. In the Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata, a larger region of North India is encompassed by the term. It’s not a surprise that Bhārata was selected as an alternative name of India in 1950. The term captures the ancient essence of this nation.

Historical references

From the ancient days of Alexander the Great, the Megasthenes (author of the Indika, in the third century BCE), and of Apollonius of Tyana (a Indian-expert in the first century CE) to the medieval days of Arab and Iranian visitors (such as Alberuni who wrote so much about the land and the people of India), all the way to the Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Europe (with heroic generalisations about India presented by Herder, Schelling, Schlegel and Schopenhauer, among many others). It is also interesting to note that, in the seventh century CE, as the Chinese scholar Yi Jing returned to China after spending ten years in India, he was moved to ask the question: ‘Is there anyone, in the five parts of India, who does not admire China?’ That rhetorical — and somewhat optimistic — question is an attempt at seeing a unity of attitudes in the country as a whole, despite its divisions, including its ‘five parts’.

Akbar was one of the ambitious and energetic emperors of India who would not accept that their regime was complete until the bulk of what they took to be one country was under their unified rule. The wholeness of India, despite all its variations, has consistently invited recognition and response. This was not entirely irrelevant to the British conquerors either, who — even in the eighteenth century — had a more integrated conception of India than Churchill would have been able to construct around the Equator.

Reference books: