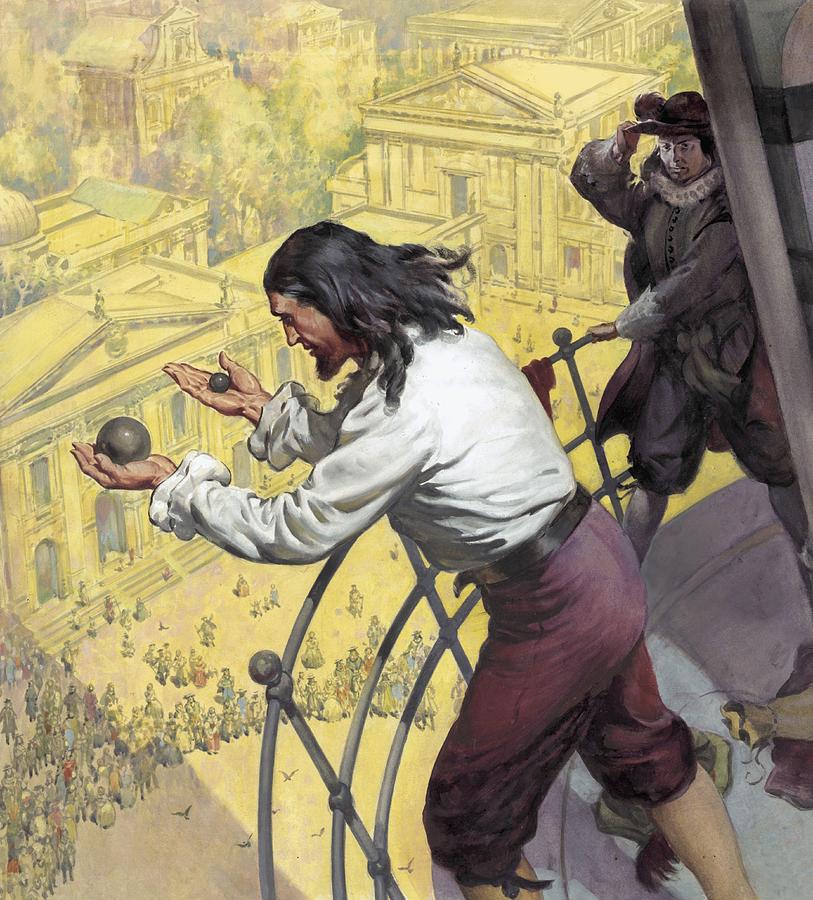

The greatest European scientist in the early 1600s was the Italian physicist and astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). In astronomy he pioneered the use of the telescope and defended the theory of a sun-centered universe, advanced by the Polish astronomer Nicholas Copernicus in 1543. His public support of Copernicus disturbed Catholic clergymen and theologians, who were convinced it threatened correct belief and authority of the Church.

In 1615 Galileo, a devout Catholic, defended his approach to science in a published letter addressed to Christina, the grand duchess of Tuscany. In the short run Galileo lost the case. The Church officially condemned Copernican theory in 1616 and forced Galileo to renounce many of his ideas in 1632. His works continued to be read, however, and in the long run his writings contributed to the acceptance of Copernican theory and the new methodology of science.

Below excerpts are taken from Galileo’s letter to the duchess.

***

Some years ago, as Your Serene Highness well knows, I discovered in the heavens many things that had not been seen before our age. The novelty of these things, as well as some consequences which followed from them in a contradiction to the physical notions commonly held among academic philosophers, stirred up against me no small number of professors — as if I had placed these things in the sky with my own hands in order to upset nature and overturn the sciences. They seemed to forget that the increase of known truths stimulates the investigation, establishment, and growth of the arts; not their diminution or destruction.

They make a shield of their hypocritical zeal for religion. They go about invoking the Bible, which they would have minister to their deceitful purposes. Contrary to the sense of the Bible and the intention of the holy Fathers, if I am not mistaken, they would extend such authorities until even in purely physical matters — where faith is not involved — they would have us altogether abandon reason and the evidence of our senses in favour of some biblical passage, though under the surface meaning of its words this passage may contain a different sense.

I hope to show that I proceed with much greater piety than they do, when I argue not against condemning this book, but against condemning it in the way they suggest — that is, without understanding it, weighing it, or so much as reading it….

The reason produced for condemning that the earth moves and the sun stands still is that in many places in the Bible one may read that the sun moves and the earth stands still. Since the Bible cannot err, it follows as a necessary consequence that anyone takes an erroneous and heretical position who maintains that the sun is inherently motionless and the earth movable.

With regard to this argument, I think in the first place that it is very pious to say and prudent to affirm the holy Bible can never speak untruth — whenever its true meaning is understood. But I believe nobody will deny that it is often very abstruse, and may say things which are quite different from what its bare words signify. Hence in expounding the Bible if one were always to confine oneself to the unadorned grammatical meaning, one might fall into error. Not only contradictions and propositions far from true might thus be made to appear in the Bible, but even grave heresies and follies. Thus it would be necessary to assign to God feet, hands, and eyes, as well as corporeal and human affections such as anger, repentance, hatred, and sometimes even the forgetting of things past and ignorance of those to come. These propositions uttered by the Holy Ghost were set down in that matter by the sacred scribes in order to accommodate them to the capacities of the common people, who are rude and unlearned….

This being granted, I think that in discussions of physical problems we ought to begin not from the authority of scriptural passages but from sense-experiences and necessary demonstrations; for the holy Bible and the phenomenon of nature proceed alike from the divine Word, the former as the dictate of the Holy Ghost and the latter as the observant executrix of God’s commands. It is necessary for the Bible, in order to be accommodated to the understanding of every man, to speak many things which appear to differ from the absolute truth so far as the bare meaning of the words is concerned. But Nature, on the other hand is inexorable and immutable; she never transgresses the laws imposed on her, or cares a whit whether her abstruse reasons and methods of operation are understandable to men. For that reason it appears that nothing physical which sense-experience sets before our eyes, or which necessary demonstrations prove to us, ought to be called in question (much less condemned) upon the testimony of biblical passages which may have some different meaning beneath their words. For the Bible is not chained in every expression to conditions as strict as those which govern all physical effects; nor is God any less excellently revealed in Nature’s actions than in the sacred statements of the Bible.

Reference Books