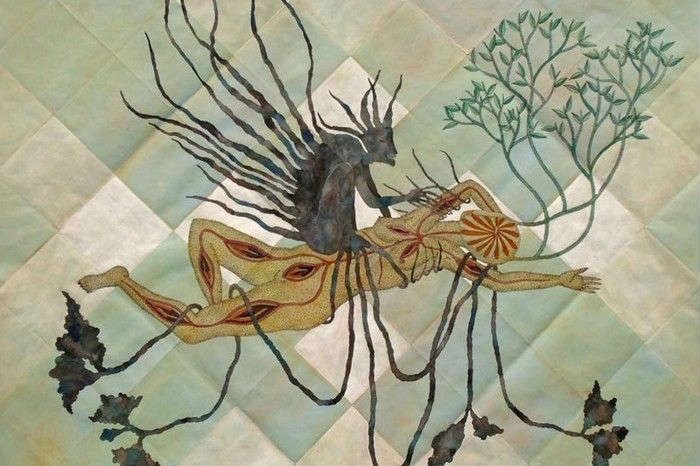

In Plato’s Symposium, Aristophanes tells a story about the origin of human beings. According to his myth, humans descend from creature who had spherical bodies, genitals on the outside, four hands and feet, two faces each, and were divided into three genders: one group had two male genitals; the second group had two female genitals; and the third group, hermaphrodites, had one of each.

Over time, the creatures became arrogant and uppity. To punish them, Zeus split them in two. In that state, they clung to their other halves, dying from hunger and self-neglect because ‘they did not like to do anything apart’. Zeus took pity on them, and invented a new plan, moving their genitals so that they could have sexual relations with each other. Each of us is a half of a human being, and each seeks his or her other half. Men who are split from the hermaphrodite desire women; women who descend from a female creature ‘do not care for men, but have female attachments’; and men who are split from a male body prefer to pursue males, and in their boyhood ‘enjoy lying with and embracing men… because they have the most manly nature, and… rejoice in what is like themselves’.

Aristophanes’ speech became a famous myth of origin, but what does it mean? At first sight, it seems to suggest that the ancient Greeks thought that some people desired only members of the same sex. Many classicists disagree, however, and point out that it is not for nothing that Plato has Aristophanes, the comic poet who is always coming up with the most outrageous, playfully ironic, and ultimately absurd suggestions such as a parliament of birds or women entering politics, tell this story.

Certainly, for most Greeks, the idea of classifying people according to the gender of the person they have sex with would have seemed downright bizarre. Antiquity was not a culture of sexual libertarianism. Sexual morality was highly regulated by moral and legal rules. However, moral preoccupations centered on sexual practices, not on the subject of desire. The ancients did not make sense of themselves in terms of sexual identities, whereas the policing of gender identity was of central importance to them.

Consider the contrast with the ways in which modern subjects make sense of their sexual experiences. Categories such as heterosexual and homosexual are a central source upon which we draw in order to make sense of our own sexuality. It is in this sense that the classical world has been described as a world ‘before sexuality’ by historians such as Michel Foucault, Paul Veyne, David Halperin, or John Winkler. The ways in which sex was conceptualised and the cultural meanings that were attached to it were radically different from today.

Classical Athenian sexual culture must be located in its social and political context. Greek society was based on the political and social rule of a small elite of adult male citizens; citizen women and children occupied a socially subordinate position and had no political rights, and immigrants and slaves had no citizenship status. More precisely, Athenian women had the status of minors and were always under legal guardianship of a male relative. Reflecting the social power of male citizens, sexual culture was organised around male pleasure.

The ancient Greeks adopted a phallocentric notion of sex, defined exclusively as penetration. While kisses, caresses, and forms of touching other than penetration were considered expressions of love, they were not considered part of the sexual domain. Sex was thus not construed in relational terms, as a shared experience reflecting emotional intimacy, but as something — penetration — done to someone else. The physical pleasure, or indeed collaboration, of the partner was broadly considered to be irrelevant. Men were encouraged to use penetrative sex for domination and control of the submissive partner. Sex reflected social and political relations of power, since men performed their social status as citizens in the arenas of war, politics and sex.

Sexual culture was closely intertwined with notions of sex and gender. Medical knowledge of the time saw bodies as fragile, consisting of liquids in a precarious balance affected by age, diet and lifestyle. Aging and, ultimately, death was understood as a process of cooling and drying out of the body. Sex itself was conceptualised as involving heating of the body. Aesthetically, the Greeks seem to have had a preference for male bodies with puny penises, with the added benefit that they were at less risk in war.

As the historian Thomas Laqueur has pointed out, the classical model of gender involved a ‘one-sex model’: since the gender was understood as fluid, men risked becoming more feminised if they lost heat, while women could become more like men if their bodies heated up. The psychological consequence of such beliefs was that gender did not appear as a stable, biological characteristic, but as an identity that was potentially under threat.

Such medical beliefs were reflected in the view held by the ancient Greeks that all women were by nature oversexed, as echoed in the myth of Tiresias, which is best known in the version in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ovid tells the story of the man Tiresias who was, for seven years, transformed into a woman by the gods, before reverting back to his male body. Having experienced sex both as a man and as a woman, Tiresias was later asked to settle a dispute between the god Zeus and his wife Hera as to whether it is men or women whose sexual pleasure is more intense. When he declared that it was women, Hera struck him blind in retaliation for having given away this female secret.

As suggested by the medical author Priscianus, erotic imagery was thought to be a cure for declining virility: ‘Let the patient be surrounded by beautiful girls or boys; also give him books to read, which stimulate lust and in which love-stories are insinuatingly treated.’ Failing that, dancing girls, or various aphrodisiac stimulants, catalogued at great length by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, were recommended. More generally, sexual imagery, and especially images of the erect phallus, a symbol of male power used to ward off evil, was present everywhere in everyday life in the ancient Greece.

Reference Books: