There is a problem, a serious cultural problem, about solitude. Being alone in our present society raises an important question about identity and well-being. In the first place, and rather urgently, the question needs to be asked. And then — possibly, tentatively, over a longer period of time — we need to try and answer it.

The question itself is a little slippery — any question to which no one quite knows the answer is necessarily slippery. But I think, in as much as it can be pinned down, it looks something like this:

How have we arrived, in the relatively prosperous developed world, at least, at a cultural moment which values autonomy, personal freedom, fulfilment and human rights, and above all individualism, more highly than they have ever been valued before in history, but at the same time these autonomous, free, self-fulfilling individuals are terrified of being alone with themselves.

Think about it for a moment. It is truly very odd.

We apparently believe that we own our bodies as possessions and should be allowed to do with them more or less anything we choose, from euthanasia to a boob job, but we do not want to be on our own with these precious possessions.

We live in a society which sees high self-esteem as a proof of well-being, but we do not want to be intimate with this admirable and desirable person.

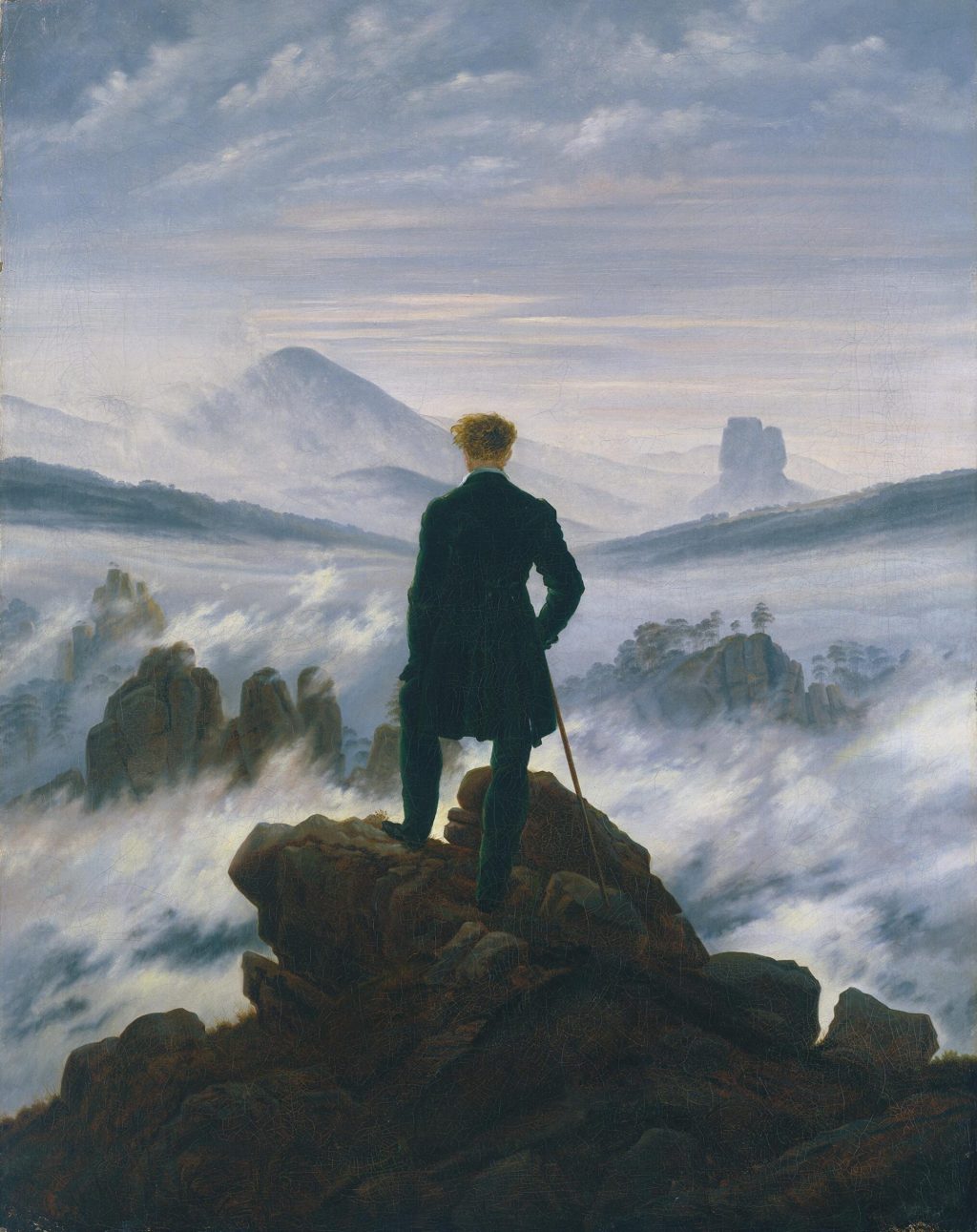

We see moral and social conventions as inhibitions on our personal freedoms, and yet we are frightened of anyone who goes away from the crowd and develops ‘eccentric’ habits.

We believe that everyone has a singular personal ‘voice’ and is, moreover, unquestionably creative, but we treat with dark suspicion (at best) anyone who uses one of the most clearly established methods of developing that creativity — solitude.

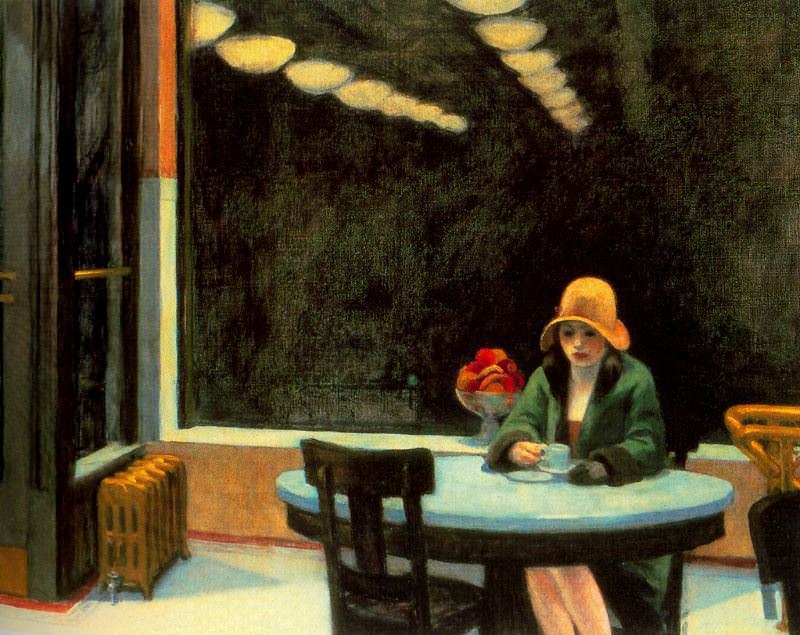

We think we are unique, special and deserving of happiness, but we are terrified of being alone.

We declare that personal freedom and autonomy is both a right and good, but we think anyone who exercises that freedom autonomously is ‘sad, mad or bad’. Or all three at once.

In 1980, US census figures showed 6 percent of men over forty never married; now 16 percent are in that position… ‘male spinsters’ — a moniker that implies at best that these men have ‘issues’ and at worst they are sociopaths. One fears for these men, just as society has traditionally feared for a single woman… But in time to ease my anxiety, a British friend came through town… ‘I want to get married,’ he said. Finally. A worthwhile man.

Vicky Ward, London Evening Standard, 2008

In the Middle Ages the word ‘spinster’ was a compliment. A spinster was someone, usually a woman, who could spin well: a woman who could spin well was financially self-sufficient — it was one of the very few ways that medieval women could achieve economic independence. The word was generously applied to all women at the point of marriage as a way of saying they came into the relationship freely, from personal choice not financial desperation. Now it is an insult, because we fear ‘for’ such women — and men as well — who are probably ‘sociopaths’.

Being single, being alone — together with smoking — is one of the few things that complete strangers feel free to comment in rudely: it is so dreadful a state (and probably, like smoking, your own fault) that the normal social requirements of manners and tolerance are superseded.

In the course of my life, I have loved and lost and sometimes won, and always strangers have been kind. But I have, it appears, been set on a life of blessedness. I haven’t minded enough. But now I kind of do. Take dinner parties. There comes a moment, and that question: ‘Why don’t you have a partner?’

Jim Friel, BBC Online Magazine, 2012

In both the above examples it is clear that thinking the single person ‘sad’ is not enough for the society. Normally we are delicate, even over delicate, about mentioning things that we think are sad. We do not allow ourselves to comment at all on many sad events. Mostly we go to great lengths to avoid talking about death, childlessness, deformity and terminal illness. It would not be acceptable to ask someone at a dinner party why they were disabled or scarred. It is conceivable, I suppose, that a person happy in their own coupled relationship really has so little imagination that they think anyone who is alone must be suffering tragically.

But… it is more complicated than that: Vicky Ward’s tone is not simply compassionate. Her ‘fears for these men’ might at first glance seem caring and kind, but she disassociates herself from her own concern: she does not fear herself, ‘one fears for them’. Her superficial sympathy quickly slips into judgement: a ‘worthwhile’ man will be looking for marriage; if someone is not, they have mental-health ‘issues’ and are very possibly ‘sociopaths’.

***

The above excerpts are taken from Sara Mailtland’s book How to be Alone. The book is published by The School of Life.