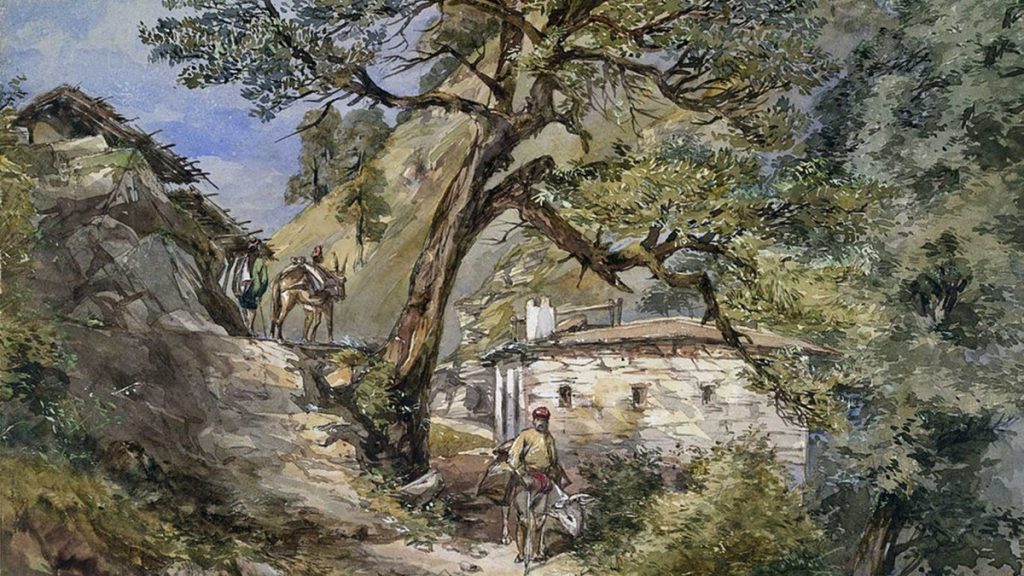

My theory of writing is that the conception should be as clear as possible, and that words should flow like a stream of clear water — preferably a mountain stream. You will, of course, encounter boulders, but you will learn to go over them or around them, so that your flow is unimpeded. If your stream gets too sluggish or muddy, it is better to put aside that particular piece of writing. Go to the source, go to the spring, where the water is purest, your thoughts as clear as the mountain air.

I do not write for more than an hour or two in the course of the day. Too long at the desk, and words lose their freshness.

Together with clarity and a good vocabulary there must come a certain elevation of mood. Laurence Sterne must have been bubbling over with high spirits when he wrote Tristram Shandy. The sombre intensity of Wuthering Heights reflects Emily Brontë’s passion for life, knowing that it was to be brief. Tagore’s melancholy comes through in his poetry. Dickens is always passionate, there are no half measures in his work. Conrad’s prose takes on the moods of the sea he knew and loved.

A real physical emotion accompanies the process of writing, and the great writers are those who can channel this emotion into the creation of their best work. Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Balzac!

“Are you a serious writer?” a schoolboy once asked me. “Well, I try to be serious,” I said, “but cheerfulness keeps breaking in!”

Can a cheerful writer be taken seriously? I truly don’t know. But I was certainly serious about making writing the main occupation of my life.

In order to do this, one has often to give up many things — a job, security, comfort, domesticity — or rather the pursuit of these things. Had I married when I was twenty-five, I would not have been able to throw up a good job as easily as I did at the time; I might now be living on pension! God forbid. I am grateful for my continued independence and the necessity to keep writing for my living and for those who share their lives with me and whose joys and sorrows are mine too. An artist must not lose his hold on life. We do that when we settle for the safety of a comfortable old age. But there is no retirement age for writers.

Normally, writers do not talk much, because they are saving their conversations for the readers of their books — those invisible listeners with whom we wish to strike a sympathetic chord. Of course, we talk freely with our friends, but we are reserved with people we do not know very well. If I talk too freely about a story I am going to write, chances are it will never be written. I have talked it to death.

Being alone is vital for any creative writer. I do not mean that you must live the life of a recluse. People who do not know me are frequently under the impression that I live in lonely splendour on a mountain top, whereas in reality I share a small flat with a family of twelve — and I’m the twelfth man, occasionally bringing out refreshments for the players!

***

Ruskin Bond is an award winning Indian author of British descent, much renowned for his role in promoting children’s literature in India. A prolific writer, he has written over 500 short stories, essays and novels.