The central fantasy behind all the noise and anguish of relationships is to find someone we can be happy with. It sounds almost laughable, given what tends to happen.

We dream of someone who will understand us, with whom we can share our longings and our secrets, with whom we can be weak, playful, relaxed and properly ourselves.

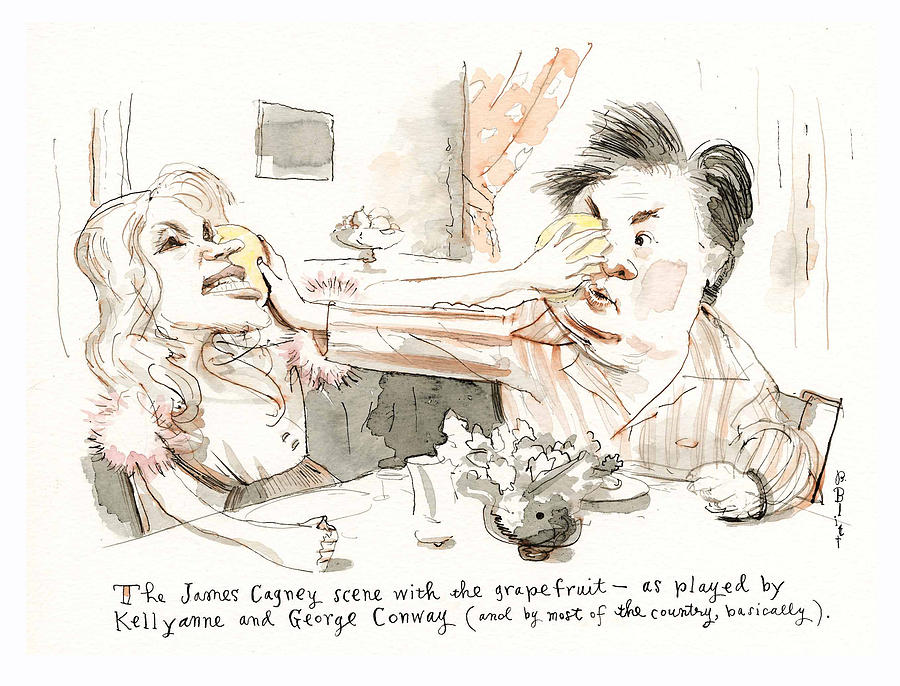

Then the horror begins. We come across it second-hand when we hear the couple yelling at one another through the wall of the hotel room as we brush our teeth; when we see the sullen pair at the table across the restaurant; and sometimes, of course, when turmoil descends upon our own unions.

Nowhere do we tend to misbehave more gravely than in our relationships. We become in them people that our friends could hardly recognise. We discover a shocking capacity for distress and anger. We turn cold or get furious and slam doors. We swear and say wounding things. We bring enormously high hopes to our relationships — but in practice, these relationships often feel as if they have been especially designed to maximise distress.

Our lives are powerfully affected by a special quirk of the human mind to which we rarely pay much attention. We are creatures deeply marked by our expectations. We go around with mental pictures, lodged in our brains, of how things are supposed to go. We may hardly even notice we’ve got such phantasms. But expectations have an enormous impact on how we respond to what happens to us. They are always framing the way we interpret the events in our lives. It’s according to the tenor of our expectations that we will deem moments in our lives to be either enchanting or (more likely) profoundly mediocre and unfair.

What drives us to fury are affronts to our our expectations. There are plenty of things that don’t turn out as we’d like but don’t make us livid either. It would be great if it could be sunny over the Easter break, but we have learned across long years that we live in a cloudy, general damp, disappointing climate, so we won’t stamp our feet when we realise it is drizzling. When a problem has been factored into our expectations, calm is never endangered. We may be sad, but we aren’t screaming. Yet when you can’t find the car keys (they are always by the door, in the little drawer beneath the gloves), the reaction may be very different.

Here, an expectation has been violated. Someone must have taken the damn keys on purpose. We were going to be on time, now we’ll be late. This is a catastrophe. You are enraged because, somewhere in your mind, you have a perilous faith in a world in which car keys simply never go astray. Every one of our hopes, so innocently and mysteriously formed, opens us up to a vast terrain of suffering.

Our expectations are never higher, and therefore more troubling, than they are in love. There are reckless ideas circulating in our societies about what sharing a life with another person might be like. Of course, we see relationship difficulties around us all the time; there’s a high frequency of splitting, separation and divorce, and our own past experience is bound to be pretty mixed. But we have a remarkable capacity to discount this information. We retain highly ambitious ideas of what relationships are meant to be and what they will (eventually) be like for us — even if we have, in fact, never seen such relationships in action anywhere near us.

We’ll be lucky; we can just feel it intuitively. Eventually, we’ll find that creature we know exists: the ‘right person’; we’ll understand each other very well, we’ll like doing everything together, and we’ll experience deep mutual devotion and loyalty. They will, at last, be on our side.

We aren’t dreaming. We’re just remembering. The idea of a good relationship isn’t coming from what we’ve seen in adulthood. It’s coming from a stronger, more powerful source. The idea of happy coupledom taps into a fundamental picture of comfort, deep security, wordless communication and of our needs being effortlessly understood and met. It’s coming from early childhood. Psychoanalysts suggest that we all knew the state of love in the womb and in early infancy when, at the best best moments, a loving parent did in fact engage with us in the way we hope a lover may. They knew when we were hungry or tired, even though we couldn’t explain. We did not need to strive. They could make us feel completely safe. We were held peacefully. We are projecting a memory onto the future; we are anticipating what may happen from what once occurred according to a now-impossible template.

We have always had dreams of happy love. Only recently in history have we imagined that they might come to fruition within a marriage. An 18th-century French aristocrat would — for instance — take it for granted that marriage was a necessary matter for reproduction, property and social alliances. There was no expectation that it would, on top of it all, also lead to happiness with a spouse. That was reserved for affairs — the real targets of tender and complex emotional hopes. The practical sides of a relationship and the romantic longing for closeness and communion were kept on separate planes. Only very recently has the emotional idealism of the love affair come to be seen as possible, even necessary, within marriage. We expect, of course, that there will be major pragmatic dimensions to our unions, involving variable mortgage rates and children’s car seats. But, at the same time, we expect that the relationship will fulfill all our longings for deep understanding and tenderness.

Our expectations make things very difficult.

The expectations might go like this: a decent partner, should easily, intuitively, understand what I am concerned about. I shouldn’t have to explain things at length to them. If I’ve had a difficult day, I shouldn’t have to say that I’m worn out and need a bit of space. They should be able to tell how I’m feeling. They shouldn’t oppose me: if I point out that one of our acquaintances is a bit stuck up, they shouldn’t start defending them. They’re meant to be constantly supportive. When I feel bad about myself, they should shore me up, remind me of my strengths. A decent partner won’t make too many demands. They won’t be constantly requesting that I do things to help them out, or dragging me off to do something I don’t like. We’ll always like the same things. I tend to have a pretty good taste in films, food and household routines: they’ll understand and sympathise with them at once.

Strangely, even when we’ve had pretty disappointing experiences, we don’t lose faith in our expectations. Hope reliably triumphs over experience. It’s always very tempting to console ourselves with an apparently very reasonable thought: the reason it didn’t work out this time was not that the expectations were too high, but that were trying to get together with the wrong person. We weren’t compatible enough. So rather than adjust our ideas of what relationships are meant to be like, we shift our hopes to a new target, another person on whom we can direct the same insanely elevated hopes.

***

The above excerpts are taken from the book Calm, published by The School of Life.