Parental horror stories about placing difficult children are all too common. But in most cases, where effective understanding and intervention starts early it need not come to that. As National Institute of Mental Health psychiatrist Stanley Greenspan shows us in his book The Challenging Child, parents can actually help their children make the most of their temperament, whatever it is. They can do this by turning challenge into opportunity, especially if they start early enough.

Who are these challenging children? Greenspan draws from the best child development research to group children into five major temperamental patterns. Greenspan is a great advocate for children and parents. Thus, he recognises that each type of child has strengths. He encourages parents to play to these strengths while compensating for the child’s vulnerabilities. He has seen how the most challenging child can turn out well. Greenspan provides all the details. Here we will simply provide an outline of his approach.

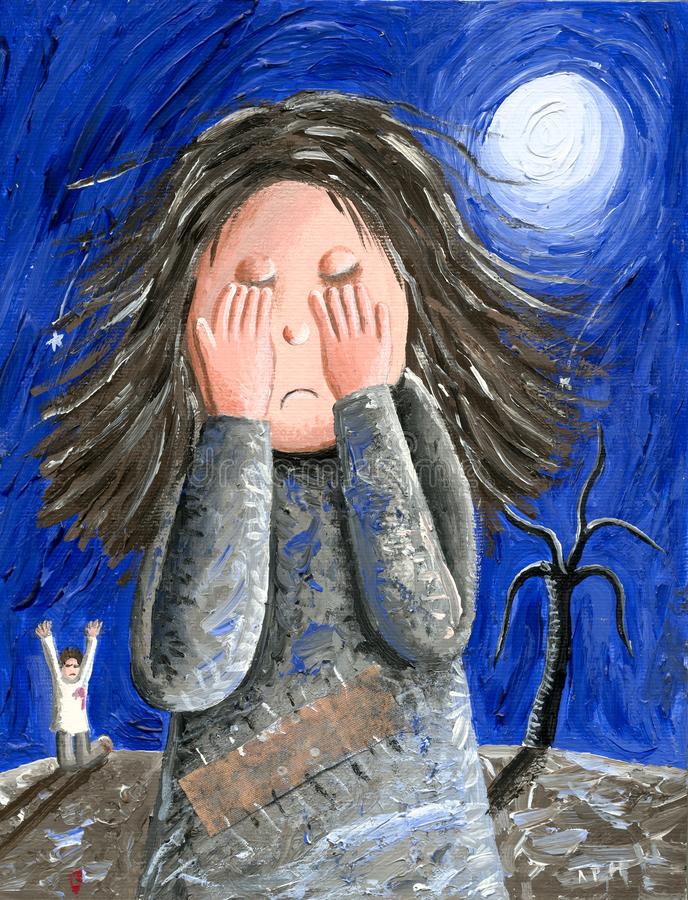

Highly Sensitive

These children feel everything more intensely than most. There are physiological reasons for this, as Carol Kranowitz points out in her book The Out-of-Sync Child. The world to them is full of extreme sensations – like being at a rock concert all the time. At each stage along the developmental way, these children find the world so intense, they react with a mixture of outrage and withdrawal. As babies, they cry a great deal and are irritable and demanding. As preschoolers they resist change and are fearful. As school-age children they are self-centered and grandiose in their fears and demands. If handled well, however, these children can become creative and insightful, and use their sensitivity as the basis for empathy and compassion. Success comes from a combination of empathy, structure and clearly established limits, encouragement of initiative, and self-observation.

Self-absorbed

In contrast to highly sensitive children, self-absorbed children often seem “easy” at the start. They make few demands and seem content to be left alone with their own inner world. As babies they sleep a great deal and don’t cry much. As they move through the first year, however, this easiness becomes less appealing because the child does not respond well to the social overtures of parents – smiling, talking, playing peek-a-boo – that are one of the main ways parents get reinforced for the efforts they invest in child rearing.

Defiant

Greenspan says it well: “Stubborn, negative, controlling – the defiant child manages to turn even the simplest activity into a trial.” Like highly sensitive children, defiant children find the world an intense experience. But unlike highly sensitive children, defiant children do not shrink from that world and whine; they seek to dominate and control it. While it is normal for children to explore the word “no” as a tool for defining who they are and how the world works, defiant children get stuck on “no.”

Transitions are often a focal point for defiance, from the everyday transitions of getting up in the morning to getting ready for bed at night. But the larger life transitions are involved in this negativism as well, from toilet training and starting school to taking on chores and meeting curfews. This negativism is usually coupled with a high level of energy and persistence, so many parents have to deal not with “no,” but with “no, no, no, no, no, no, no, no….” Add to this cleverness (to defeat parental arguments), deceptiveness (to get around your rules), and stubbornness, and it is long, exhausting road for the parents of a defiant child.

Inattentive

While the issue of “attention deficit” has become a common theme in the way parents and teachers view children, Greenspan is critical of simplistic thinking about this issue, particularly when they are diagnosed too readily as having Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). He says, “In some cases, children believed to suffer from ADD are being medicated without adequate medical developmental, and mental health evaluations to determine whether they actually have an attention difficulty or some other challenges and whether medication is needed.”

He offers parents a more sophisticated view of this issue by pointing out that the best research shows that paying attention is composed of many specific mental processes and that these processes work in specific contexts, not across the board. This is crucial to understanding inattentive children and to knowing how to help them proceed developmentally. For most children, it is the details of school life that are the biggest problem – writing, repetitive arithmetic problems, and other features of the “boring” routine of day-to-day life in most schools.

Active/Aggressive

Interestingly, Greenspan links together “active” and “aggressive,” and he takes a different tack than many temperament researchers do. But his link offers an important clue to the larger question of rearing such children successfully. Children are not born aggressive; they learn to be aggressive. But children are born active and impulsive, and unless the activity and impulsivity are handled correctly, they can serve as the foundation for building aggression. The long-term payoff of high or hyper activity levels gone positive is seen in the careers of athletes, soldiers, and many of society’s movers and shakers. On the other hand, the long-term costs of this same hyper level of physical activity channeled in destructive ways can be seen in prisons.

Greenspan writes: There is probably no greater challenge for a parent than coping with an angry child. If the active/aggressive child’s temperament is allowed to control parental response, the long pattern is likely to be one of accentuating the inherent challenges into a spiraling pattern of difficulty. But if the parents understand the cause-effect chains that arise when activity/aggression controls their interaction with the child, they can de-escalate and re-channel and calm the child. At the extremes, when these children face parents who are abusive or neglectful, they are at great risk of becoming delinquent, anti-social and violent.

Now that we know, what can we do?

Once we move away from blame, a whole new world opens up. As the Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh reminds us, ” Blaming never helps,” whether it is blaming others, blaming ourselves, or blaming our children for being the boy or girl he or she is. Patience, understanding, and appropriate responses – that is what has a chance to help. Stanley Greenspan captures this nicely when he entitles the first chapter of his book “You’re Not the Cause, but You Can Be the Solution.” Moving beyond assigning or feeling blame is liberating and empowering; it turns our attention to what we can do to help guide our children on a positive path and to support parents, no matter what their child’s temperament.

When it comes to dealing with temperamentally difficult children, there are four crucial things for us to do. First, we must know our children as they are, not as we would like them to be. We must use the conceptual tools of child psychology. One of the virtues of thinking like a scientist is that it permits us to discipline ourselves as we observe others. It means not imposing preconceptions or bias or getting caught up in what actually is coincidence but may appear to be something else in the fervor of the mind to make sense of things.

Second, we must know ourselves. Let’s not forget that we adults have temperaments underlying our personalities too. We, too, can have tendencies to be fussy, self-absorbed, defiant, inattentive, and aggressive, and we can be highly sensitive or detached, lethargic or hyperactive, emotionally unresponsive or relatively insensitive. What parents bring to the child development equation is important because it shapes the way we offer alternative pathways for children, particularly challenging children. In her book The Highly Sensitive Person, psychologist Elaine Aron outlines the great challenges faced by highly sensitive parents. Highly sensitive parents must develop a very high level of self-awareness and self-control to deal with a challenging child. Knowledge is power, and knowing your own temperamental strengths and weaknesses is the first step towards mastering yourself so that you can be a more effective parent.

We must understand this second point in light of the third, however. Biology is not destiny. With rare exceptions, temperament affects only the probabilities, the odds that a child will head in a particular direction. Temperament is only one factor in the developmental equation. Once we accept this reality, we can move toward change.

While temperament stems from innate characteristics, it need not be immutable, locked in, and fixed. Some children are temperamentally predisposed to be fearful when confronted with new things. Yet guided experiences can mute and even alter that disposition, and dramatically reduce its role in the child’s future behaviour and experience of the world. In short, enlightened action can change fear’s place in a child’s social map. Greenspan is even more optimistic. He notes that “early care, in fact, not only can change a child’s behaviour and personality, but can also change the way a child’s nervous system works.”

Fourth, we can accept every child as we seek to shape and direct that child. A quarter of century ago, anthropologist Ronald Rohner studied rejection in cultures around around the world. In his book They Love Me, They Love Me Not, he found that in every culture, rejected children are more likely to develop whatever social and psychological pathologies are at issue in that society. This connection was strong, he said, that rejection was a “psychological malignancy,” an emotional cancer.

Temperament is really about the diversity of containers in which a child’s true essence comes to us. Their physical vessels differ in temperament as they do in their physical and mental abilities and sexual orientation. Our goals is always to find a way to accept and love the spiritual being while at the same time smoothing the way for the physical child to make his way in the world, morally, emotionally, socially, economically, and politically.

***

The above excerpts are taken from the book Parents Under Siege: Why You Are The Solution, Not The Problem, In Your Child’s Life, written by James Garbarino and Claire Bedard.