“Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proven innocent,” says George Orwell in the opening lines of his essay Reflections on Gandhi. He wrote it a year after Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in New Delhi on 30 January, 1948.

You can listen to the complete essay below:

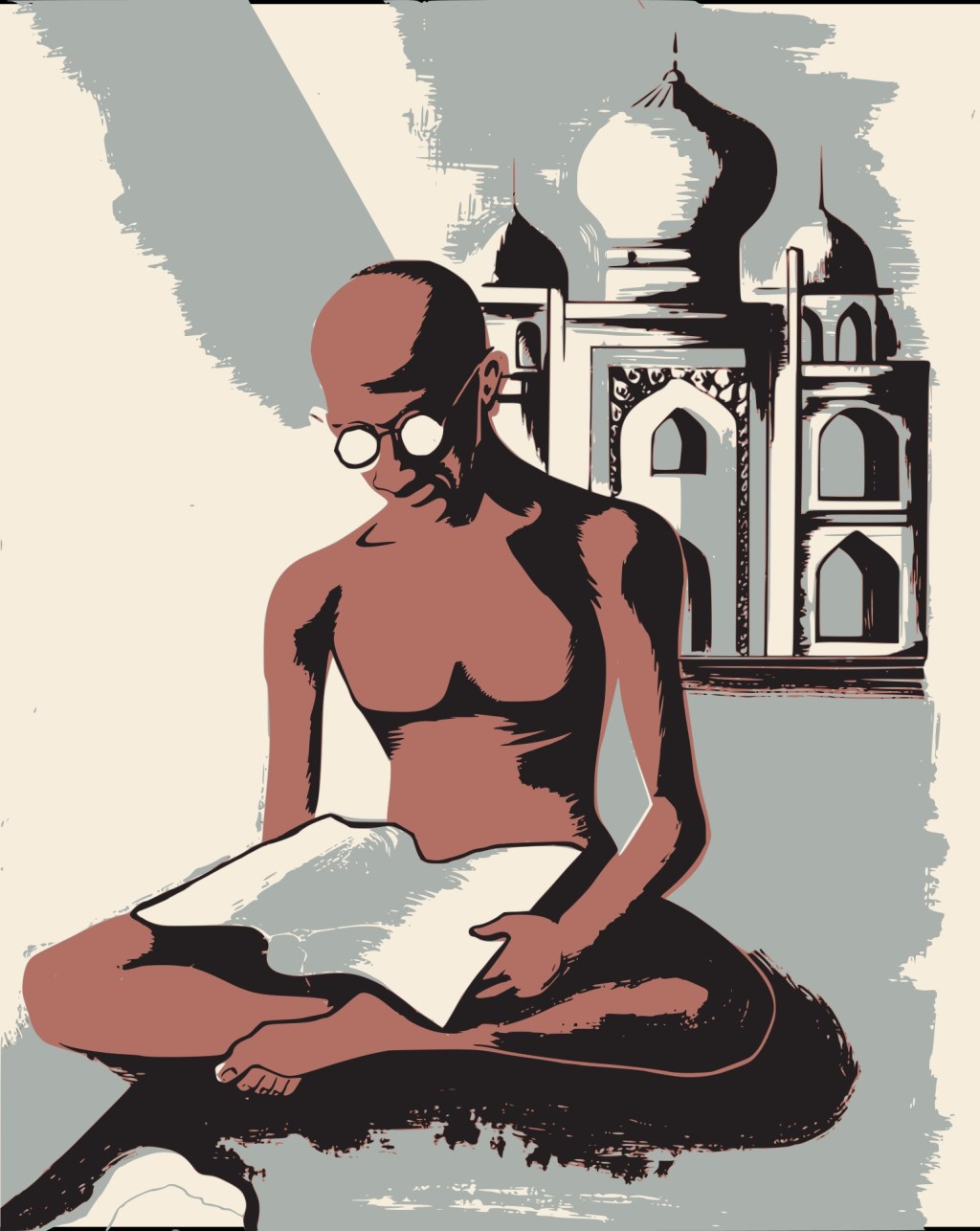

In his essay, Orwell tries to examine Gandhi’s principle of Satyagraha (holding on to truth) and how he applied this principle during his political struggle against the British. Orwell goes on to explain Gandhi’s personality, and what role it played in his political ideology. Let’s take a closer look.

As clear from the opening lines, Orwell sees Gandhi as some kind of saint, or at least someone who is pretending to be one. Orwell is being too harsh, you could say; and you are probably right. Further, he confesses that Gandhi did not make a good impression on him, at least initially. The things that one associated with Gandhi – home-spun cloth, “soul forces” and vegetarianism – he found unappealing. He found Gandhi’s whole agenda medievalist in nature as it ignored the modern reality. But, perhaps his most surprising criticism of Gandhi was with regard to the latter’s role within the British colonial structure. “They (the British) were making use of him,” argued Orwell. “Since in every crisis he would exert himself to prevent violence – which, from the British point of view, meant preventing any effective action whatever – he could be regarded as our man.”

The above critique is scathing and – quite naturally – raises a lot of eyebrows. The essay, however, tries to evaluate Gandhi in the entirety of his works. Orwell admits that the British officials genuinely admired and liked him. That no one could ever suggest that Gandhi was corrupt, or had any malice in him. In fact, Orwell made a concession that no commentator today ever makes: that we should not judge Gandhi by those impossible high standards which instinctively come to mind because of his personality. Instead we must see him as he was; for his virtues and vices. When we do that, we find that he was a man of courage. And though he came of a poor middle-class family, started life rather unfavourably, and was probably of unimpressive physical appearance, he was not afflicted by envy or inferiority. He could approach everyone in the same way, which helped him make friends wherever he went. And all these people – including his worst enemies – would agree that Gandhi was an interesting and unusual man who enriched the world simply by being alive.

Orwell reflects on the personal and political life of Gandhi, and one can see it as some kind of clash of two value systems. Gandhi supported vegetarianism, Orwell did not; Gandhi preferred brahmacharya (celibacy), Orwell did not; after all, Gandhi was religious and Orwell was not. Because there are fundamental differences in two value systems, there arise a number of points of disagreement. What bothered Orwell the most, as it’s apparent from the essay, was Gandhi’s superstitious behaviour which often brought misery to him and people around him.

Gandhi’s pacifism has often been criticised by people – and so is the case in this essay. As mentioned earlier, Orwell saw him as a stretch-bearer on the British side on multiple occasions. He says, by pretending that in every war both sides are exactly the same and it makes no difference who wins, Gandhi made it hard for himself to be on the right side.

This appears problematic when you read Gandhi’s views on Auschwitz in Louis Fischer’s Gandhi and Stalin. According to Fischer, Gandhi’s view was that the German Jews ought to commit suicide, which “would have aroused the world and the people of Germany to Hitler’s violence.” After the war he justified himself: the Jews had been killed anyway, and might as well have died significantly. Clearly, this was nothing short of inhumane on Gandhi’s part. Similar accusations were made against him during Hindu-Muslim riots when he requested Hindus to practice non-violence, no matter what? – that fuelled a lot of anger and hatred, and perhaps was one of the causes behind his assassination. Orwell makes an interesting point that Gandhi’s non-violence as political tool could only work as long as the regimes were kind to him. Is there a Gandhi in Russia at this moment? he asks. And if there is, what is he accomplishing?

Despite all the virtues-vices, agreements-disagreements, and praises-criticisms, Orwell ends the essay on a much more positive note. He says: One may feel, as I do, a sort of aesthetic distaste for Gandhi, one may reject the claims of sainthood made on his behalf (he never made any such claim himself, by the way), one may also reject sainthood as an ideal and therefore feel that Gandhi’s aims were anti-human and reactionary; but regarded simply as a politician, and compared with the other political figures of our time, how clean a smell he has managed to leave behind!